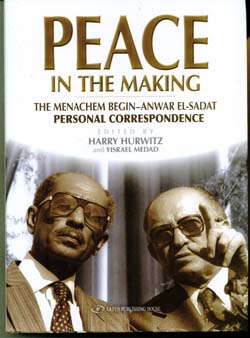

Peace in the Making: the Menachem Begin-Anwar El-Sadat Personal Correspondence, edited by Harry Hurwitz and Yisrael Medad, Gefen Publishing House, 2011, ISBN 978-9656-229-456-2, 349 pages including appendices and footnotes, price unlisted.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—It is hard not to feel wistful while reading this correspondence, which began with such hope, and then became bogged down by realities that neither Menachem Begin nor Anwar el-Sadat could control. Their correspondence ceased suddenly with Sadat’s assassination – his violent end in some measure prompted by the very relationship he had forged between Egypt and Israel.

Now, with violence in Egypt again topping international news, this book demonstrating how the two former enemies began to cooperate in Middle Eastern affairs provides welcome historical background. If the Muslim Brotherhood is taken into whatever government may someday succeed Hosni Mubarak (who has been in power since Sadat’s assassination), will the work of Begin, Sadat and their mediator, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, all go for naught?

Sadat surprised the world in 1977 when he announced that he would travel anywhere in the world, even to Jerusalem, to make a comprehensive Middle East peace with Israel. Peace between Israel and Egypt was relatively easy to accomplish. Over time, Israelis withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which they had conquered in the 1967 Six Day War and had retained in the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Sadat surprised the world in 1977 when he announced that he would travel anywhere in the world, even to Jerusalem, to make a comprehensive Middle East peace with Israel. Peace between Israel and Egypt was relatively easy to accomplish. Over time, Israelis withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which they had conquered in the 1967 Six Day War and had retained in the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

But that was not—nor could it be – the totality of what Sadat had sought. He stressed in letter after letter, and speech after speech, that the Israel-Egypt peace must be a building block for an overall Middle Eastern peace; that it was not his intent to separate himself from the rest of the Arab nation. In particular, he insisted that the Palestinians be given a state of their own.

While this does not sound so radical today, it was far more scary and controversial in the days of Begin and Sadat. The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) was then condemned as a terrorist organization, unworthy of being represented on the international stage in any settlement with Israel. For its part, the PLO denounced Sadat’s efforts in the Palestinians’ behalf. Sadat wanted Israel to make progress with the Palestinians; yet there was no one to make progress with. Some might say that is still the situation today.

Even Jordan refused to join Egypt in its effort to build peace with Israel, and as it grew increasingly isolated in the Arab world, Egypt simultaneously was frustrated by what Sadat considered Begin’s legalisms and lack of a sweeping vision. He wanted from Begin some grand gesture, equivalent to the gesture that Sadat had made in flying to Jerusalem. Begin could not provide Sadat with what he wanted – whereas he was willing to give his trust and friendship to Sadat; neither the Palestinian Arabs nor other Arab nations were willing to do anything that suggested such an effort would be worthwhile. Sadat was a dreamer; Begin a pragmatist.

Despite the frustration they had with each other, despite the numerous occasions when they would scold each other in their correspondence, mutual respect developed between the two men – as can clearly be seen in the correspondence. They took pride in doing what no one else had done before. Both subjected to harsh criticism, they developed a friendship akin to those of soldiers in the trenches. And they both were honored with Nobel Peace Prizes.

What impressed me, reviewing events that I vividly remember watching unfold on my television screen, was how dogged and determined both men were. In spite of the flare ups of anger and the pressures both were under from their domestic and international opponents, they reached out to each other. The two leaders’ letters are filled with courtesies, each typically ending with personal regards for each other’s wives. Perhaps that courtesy, that determination, really is what diplomacy and leadership are about. I recommend this book not only as background to the current crisis, but as a case study in interpersonal relationships.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World