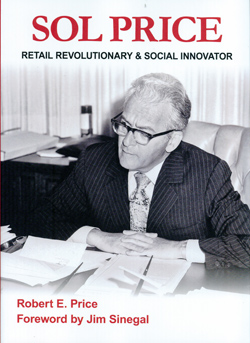

Robert E. Price, Sol Price: Retail Revolutionary & Social Innovator, San Diego History Center, 2012, ISBN 0-98868060-2; 223 pages.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Next time you go into a Costco around the noon hour, and build an ersatz lunch by sampling the free offerings from food carts, be aware that the people at Costco know what you are doing — and they approve!

SAN DIEGO — Next time you go into a Costco around the noon hour, and build an ersatz lunch by sampling the free offerings from food carts, be aware that the people at Costco know what you are doing — and they approve!

Food sampling was started by Price Club and kept by Costco after the two high-volume, low-markup operations merged. Robert Price — son of the legendary Sol Price, who revolutionized the way Americans shop — explains in this candid combination biography/ autobiography: “…(T)he sampling increased sales both because members liked the products and because of the psychology of the ‘reciprocity rule,’ people’s subconscious desire to reciprocate when receiving something for free.”

Robert Price was at his late father’s side throughout the time that Sol was building the Price Club empire, and, in fact, was credited by Sol for being the author of many of the ideas for which Sol routinely received credit, probably because of his previous successes as the creator of Fedmart.

Anyone who knows Robert Price knows how self-effacing he is, and so it is not surprising that the book is presented as a biography of his father. But, as would be the case with any team, it’s hard to divorce the author from the subject. Could Gilbert write a biography of Sullivan without mentioning the part he also played? Could Ira Gershwin write a biography of his brother George? So clearly, Robert Price’s book is not simply a third-person research project — although there are some elements of that — it is a first-person account of his and his father’s remarkable forays not only into business but into philanthropy.

Sol Price built his businesses around his highly developed social consciousness. Instead of running from unions, he embraced them, saying there needs to be a balance between workers and employers. He also faced the issue of segregation head-on when he opened a Fedmart in San Antonio in 1957. Robert quoted his father as follows: “Segregation was interesting. The department stores had black customers. Nobody objected to taking money from blacks, it was just sitting down with them.” So, Robert added, “Sol decided to deal with the problem of segregation in Fedmart’s San Antonio snack bar by eliminating tables and chairs. Everyone stood up while they were eating — whites, blacks and Hispanics ate together without incident.”

Business students will appreciate Robert’s candor in explaining his family’s practice of embracing what he called “the intelligent loss of sales.” Built on the idea that customer demand is more sensitive to price than to selection, Fedmart typically would offer only one size of a product instead of multiple sizes. The prices of larger-sized items were better per ounce for the customer. “Fewer items result in reduced labor hours throughout all the product supply channels: ordering from suppliers, receiving at the distribution center, stocking at the store, checking out the merchandise and paying vendor invoices. Put simply, the cost to deal with 4,500 items is a lot less than the cost to deal with 50,000 items.” Well what about the customers who simply didn’t want to buy the larger-sized item? That, answered Robert, “was the intelligent loss of sales.”

After Fedmart was acquired by a German company, which soon ousted Sol Price and abandoned some of his business principles, the Prices decided in 1976 to form the Price Club, which was different from Fedmart in that it was a “club” for small business owners. By purchasing massive quantities of products from manufacturers, the Price Club was able to get lower prices, and pass them on to business customers willing to transport the merchandise from the Price Club warehouse to their stores or offices. Businesses paid a yearly fee of $25 to join the club, which provided working capital to Price Club.

The new business was a success but eventually the Prices decided that Costco — headed by their own former employee Jim Sinegal (who wrote the forward to the book)– could do a better job managing the sprawling, publicly-traded company. Having acquired significant wealth, the Prices wanted to focus their efforts on creating new businesses — such as PriceSmart retail operations in Central America and real estate operations in the United States — and upon various philanthropic endeavors, especially in the wake of the fatal brain cancer suffered by Robert’s teenage son, Aaron.

Aaron’s death led to the Prices donating large sums of money for brain cancer research and treatment at such venues as San Diego Hospice and the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center. The Prices also became involved in a program at the University of San Diego to safeguard children’s health via advocacy for such reforms as mandatory use of bicycle helmets and fencing around swimming pools. They also created the Aaron Price Fellows Program, which mentored high school students for three years, letting them see government and business behind the scenes in meetings with top executives and government officials. The woman whom the Prices chose to lead this project eventually became a government official herself — now Congresswoman Susan Davis.

Interest in education led the Prices to give the lead $2-million gift for the Price Center (student union building) on the UCSD campus and to persuade Sol’s 91-year-old friend Mandel Weiss to donate the funds for the on-campus Mandel Weiss Theatre. Robert commented that Weiss “remarkably lived another ten years, during which time he immersed himself in the life of the theatre. According to Sol, Weiss may have been the only person who ever found his life’s greatest joy and fulfillment during his 90’s,”

Longtime San Diegans who are part of the Jewish community, or are familiar with it, will recognize some of the other Southern California personalities who figure in the Price story: his father-in-law Max Moskowitz, wife Helen Moskowitz Price, Judge Jacob Weinberger, Ben Weingart, Isadore Teacher, Max Rabinowitz, Leo Greenbaum, Rick Libenson, Alan Bersin and Murray Galinson.

San Diegans will also recognize a roll call of civic leaders with whom Price had fruitful relationships: City Councilman William Jones, UCSD Chancellor Richard Atkinson, SDSU President Stephen Weber, City Manager Jack McGrory, attorney Paul Peterson — the list goes on and on.

Sol was often critical of the Israeli government, believing it could do much more both for its Arab residents and to bring about peace with its Palestinian neighbors. His disagreements, however, did not stop him from extending his philanthropy to projects in Israel.

The Prices donated in particular to two important projects in Israel. They underwrote various animal exhibits at the Jerusalem Zoo, enthused by the fact that institution was one of the few in Israel which attracted all types of people, religious and secular, Arab and Jew.

They also worked with Tel Aviv University on a revitalization project for the Arab neighborhoods surrounding the Port of Jaffa — a project that in some ways paralleled the City Heights project in San Diego.

A major philanthropic effort on the part of the Prices continues to be the City Heights redevelopment area in which they marshaled private foundation money to revitalize an underserved part of the city, which has been the home to immigrants from many lands.

With money from Price Charities and the Weingart Foundation, the Prices have expanded public services and educational opportunities in this mid-city area, all the while trying to pace development in such a way that the upgraded area still would be affordable for its original residents. An outgrowth of the City Heights redevelopment was an educational program run by San Diego State University, utilizing Hoover and Crawford High Schools, Rosa Parks Elementary School and Monroe Clark Middle School as teaching laboratories. One aspect of this program was the regular use of Balboa Park’s museums and other facilities on Mondays by students of the Rosa Park Elementary School — a program of cultural enrichment benefitting students who might otherwise have been socially isolated from such opportunities.

Robert suggests his father’s legacy is not so much the projects he financed, but the people who were influenced by his ethics and commitment to social justice. Key among those is Robert himself, who continues to be an important philanthropic force in San Diego.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com