-Fifteenth in a Series-

By Donald H. Harrison

LETHBRIDGE, Alberta, Canada – It’s a matter of happy circumstance that Lethbridge is the first Canadian city of moderate size that a traveler from U.S. Interstate 15 will connect with after crossing the U.S.-Canada border.

My grandson Shor and I, making a trip from the bottom of Interstate 15 in our home city of San Diego, California, to the top of that highway at the Canadian border, decided we should make Lethbridge the capstone of our 1,500-mile I-15 journey. And while we were at it, we decided, we would see what kind of a Jewish story we could find in illustration of this publication’s motto that “there’s a Jewish story everywhere.”

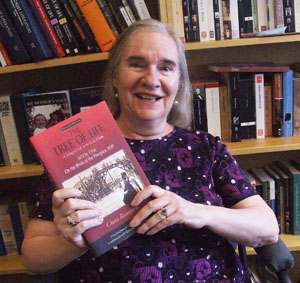

It didn’t take us long to learn about Goldie Morgentaler, who teaches Victorian and Yiddish literature at the University of Lethbridge. She agreed to be interviewed over sushi lunch, and I am pleased to say that we hit it off so well that we continued the conversation with her and her husband Jonathan Seldin, a retired mathematics and computer science professor, as well as visiting brother-in-law Daniel Seldin, over dinner in Ric’s Grill, a restaurant that intriguingly occupies the top of a 12-story high converted water tower. Morgentaler also conducted us on a tour of some of Lethbridge’s sites and Jewish places.

I learned that the professor is of famous lineage—her mother, Chava Rosenfarb, having been a Yiddish-language writer for whom book introductions have been penned by no less than Elie Wiesel, and her father, Dr. Henry Morgentaler, being Canada’s best-known abortion advocate who was tried and imprisoned for performing illegal abortions, even though juries refused to convict him. The way he was sent to jail was that an appeals court reversed a jury’s acquittal, setting off a legal hullabaloo resulting in Canada adopting a law preventing courts from reversing jury verdicts. That law is named for Dr. Morgentaler.

There are substantive Wikipedia articles about her father and her mother, who were divorced from each other, and one of shorter length about Goldie herself. As tempting as it was to discuss her parents’ careers in detail, I felt it important, in the time we had for interviewing, to learn more about Goldie’s experiences in a town where the Jewish population has shrunk almost to zero.

When she was an undergraduate at Bennington College in Vermont, she participated in a New York City work-study program which found her often alone. A bookstore near her residence became her haunt, and one day she picked up a copy of Dickens’ Great Expectations.

“I read it and I really fell in love,” Morgentaler recalled. “I thought he was the most wonderful writer and I still do.”

But, I asked, wasn’t the character of Fagin in Oliver Twist an anti-Semitic caricature of a Jew? “Anti-Semitic… why?” asked grandson Shor, a bit startled. The professor, showing some of her classroom style, said people who have only seen the musical Oliver might not think so, because Fagin was “sanitized,” but anyone who reads Dickens’ book would note the ugly descriptions of “the Jew Fagin.”

“What surprised me was how appalling the portrait was,” she confided. “Some of the passages that describe Fagin make your hair stand on end.”

She related that Dickens sold his home to a Jewish couple and was pleasantly surprised when, contrary to stereotype, they did not try to get the best of him financially. “The woman of the couple (Eliza Davis) wrote him a letter saying ‘how could you have written Fagin?’ And he defended himself, and it sort of stuck in his craw, and she said ‘you are the great humanitarian, Mr. Dickens, how could you have written this?’ He defended himself but then he was in the middle of writing Our Mutual Friend and he put in a very good Jew (Mr. Riah) in that book.

“He wrote another Jewish character, who was a saint. So he went from one extreme to another. That is anti-Semitic from the other side, this character was so good….”

Morgentaler told us that she was less disturbed by Dickens’ “genteel” anti-Semitism, for which he tried to atone, than she was by the way he treated his wife, Catherine. His abuse of her was “beyond the pale,” said Morgentaler.

“The wife had 10 children in 12 years and he lost interest in her – the old story – he fell in love when he was 45 with an 18 year old actress and instead of telling his wife that the marriage was over essentially, he called in workmen to brick up the bedroom wall that separated the bedroom from the dressing room – and he would sleep in the dressing room and he left her the bedroom, but he didn’t even tell her. He insisted that she go pay visits to his girlfriend, at a time when women really had no rights at all, and he wrote things that she was crazy, this and that, really very nasty to her.”

After completing her doctorate in English literature at McGill University, Morgentaler sent out resumes for scarce jobs as a professor. She had mixed emotions when she was accepted by Lethbridge—on the one hand, she could at last pursue her chosen profession. On the other hand, Alberta was not then considered by her fellow Montreal Jews as a particularly friendly place to live. A popular political movement in the western province was the Social Credit party, some of whose leaders won offices by promising, among other things, to bring down international Jewish bankers. And there was a notorious high school teacher, Jim Keegstra, who made headlines by teaching that the Holocaust was a fabrication – eventually getting himself convicted for hate speech.

In that Morgentaler’s specialty was Victorian literature, in an English-speaking province, such a specialty ought to be appreciated. So, what the Dickens! She took the position.

I asked if it were a greater challenge to teach Jewish literature than English literature in Alberta. Her answer surprised me. The Bible, of course, is a well-known piece of literature; its stories often serving as the bases for literary allusions, metaphors and analogies. To her surprise, she said, there were many graduates of Canada’s secular schools who had no knowledge of the Bible at all, not even a rudimentary knowledge. Some of her students actually had never heard of Adam and Eve. So, it was hard enough teaching English literature in a classroom where—except for the students who came from private Bible Belt schools—almost every literary allusion had to be explained.

Jewish literature, detailing lifestyles unknown to a majority of Alberta students, required the professor to build even more background into her lectures. When Morgentaler created the syllabus for her class, she had to assume that her students were blank slates, tabula rasa.

How sad this was! Given students knowledgeable about Eastern European Jewish life, Morgentaler could have led stimulating discussions about the works of her own mother, Chava Rosenfarb, which she herself had translated from Yiddish to English. I have read Survivors, a book of seven short stories by Rosenfarb, most of them dealing with the mental anguish from which Holocaust survivors could not escape, not even after establishing new lives for themselves in Canada. I look forward to reading Rosenfarb’s book of poems, Exile at Last, and afterwards launching into her trilogy, The Tree of Life, about life in the Lodz Ghetto where Rosenfarb and Dr. Morgentaler had known each other since childhood.

To be able to discuss the nuances of these books, why Rosenfarb chose this or that phrase; how minute description of the environment was important for establishing the mood of her literary works, and Rosenfarb’s apparent fascination with people’s eyes (often called windows into the soul) – any of these topics could have occupied an enjoyable and revealing period of class time! Although Morgentaler did have some motivated students—especially after she made the course a third-year offering “when students are more mature,” – not enough of them had sufficient multi-cultural experience to warrant offering the course on a regular basis.

“It’s very hard,” Morgentaler sighed.

I asked if the Province of Alberta turned out to be as anti-Semitic as she had feared before accepting the job. Morgentaler responded that while there have been anti-Israel demonstrations at Lethbridge University (including the Apartheid Week that Palestinian sympathizers have sponsored at other universities throughout North America), direct anti-Semitism seems to have decreased. Many of the Bible-belt Christians who live in the area, in fact, are quite vocal in their support for Israel, she said.

Commenting on the O-Sho Japanese Restaurant where we ate, Morgentaler noted that Japanese-Canadians play prominent roles in the city, having opted to remain in Lethbridge after they were forcibly removed from British Columbia at the onset of World War II and relocated to Canadian Midwest. What with immigrants from various countries, and the university faculty also present, the city has become more cosmopolitan over the years.

A whirlwind tour took us past a building that once was Lethbridge’s synagogue, but which today houses the Ferrari Westwood Babits architectural offices. When the tiny Congregation Beth Israel sold the building it no longer could afford to keep up, it arranged for the chapel to remain available for its use. So there are Torahs within the architectural building and the small Conservative congregation struggles to muster a minyan so they can be properly read on Yom Kippur and on days when its few members have a yahrzeit to commemorate.

We also saw the sprawling University of Lethbridge campus where views are framed by what is said to be the longest and highest trestle bridge in the world, 5,327.625 feet in length and 314 feet in height, and by the undulating coulees, upon which Morgentaler frequently casts her eyes with great pleasure from the solitude of her academic office.

A high point of the tour was visiting Klinger’s, a clothing store owned by Cyril Serkin, who described himself as the last remaining Jewish merchant in Lethbridge. He arrived in 1951 from Iasi, Romania, to work there for his uncle, Jack Klinger, who had established the store during the 1921. Klinger initially had come to Canada to work for his uncle, a brother of Serkin’s grandmother. Today, at age 80, Serkin says he has watched the Jewish community atrophy.

“When I came to Canada,” he said, “there were 70 families. Today there might be six active Jewish families.” He said this was due to “normal attrition, people die and the kids move out. I have three children and they all live in the States, two in Boston, one in New York. Everybody leaves, they die, or they retire and they move to warmer climates.”

He took out an old list of synagogue members, pointing to each name on the list. “Let’s see,” he said. “This one’s Jewish, married to a Mormon. This one, she died. (Another) also died. She moved to Calgary. She died. This guy’s wife died. This guy had a photographic shop. There’s me and my wife. There’s my brother Dave and his wife. That one died. This guy moved. Half of those guys are gone. So you are looking at six or seven families!

“We used to have a rabbi, but we couldn’t afford one anymore,” said Serkin. “You’d have to pay a salary of $60,000 to $70,000 and no one had that kind of money.” For a while, there was a lay leader who used to come from Calgary, but no more, Serkin said.

Most of the Jews in the Lethbridge community were merchants, professionals or cattle buyers, he recalled. Today, he said, there are a few academics besides Morgentaler, “but they are not involved with the community.”

Occasionally, he runs into anti-Semitism, he said. “People, the way they talk to you; the way they act toward you, I still hear it today. It’s never going to disappear. They belittle you. I’m used to it, but sometimes I throw them out. Usually, I can’t do anything about it. They’ll say things like, ‘You’ve got to give me a good deal – you’re a Jew.’ Or ‘don’t you Jew me down.’ Sometimes, they’ll say, ‘we’re going to finish you!’”

On the other hand, there are many customers who like Israel and Jews. And, he said, there is a group of people affiliated with the Jews for Jesus movement. “They try to do things together with us, but we have nothing to do with them.”

At dinner, Morgentaler said she and her husband probably will remain in Lethbridge for a few years, until she decides to retire. Thereafter, she said, she probably will move to Toronto, where her mother the writer, bequeathed her a condo.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

IF YOU GO: We stayed at the smoke-free Best Western Plus at 209 41st Street South, where they had free wi-fi in the rooms, an indoor pool with waterslide, and free breakfast.

____________________________________________________________________________________

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Pingback: Yiddish literature exponent among UCSD lecturers - San Diego Jewish World

I worked for Cyril and Haim for about 6 months in 1980. They were harsh but fair people to work for taught me quite alot about the value of work. Glad to see Cyril is still around he’s a good man.

Pingback: Lodz Ghetto again comes alive in book, lecture - San Diego Jewish World

I absolutely loved this article, Don and the entire series this summer. BRAVO.