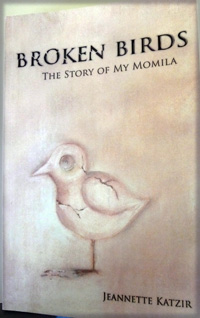

Broken Birds: The Story of My Momila by Jeanette Katzir, www.brokenbirds.com , 2009, ISBN-10: 978-0-615-27483-6, 375 pages, $17.95

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – I once had a friend who seemed to take sustenance from hearing about other people’s troubles. She had a bundle of her own problems, and seemed to light up learning, confirming and analyzing the details of the travails other people were having. This memoir by Jeanette Katzir about a family of five children born of two Holocaust survivors would have kept my old friend illuminated for weeks. She would have been energized by reading about all the tsuris among the brothers and sisters (whose names are changed)—tsuris that had them accusing each other of cheating in business dealings and even suing each other over their inheritance from their mother.

So I can’t say that this kind of book isn’t for everybody, but certainly that dominant portion of Broken Birds wasn’t for me. I was uncomfortable with the author washing her family linen in public, telling the world about trivial battles that affected no one outside the family and therefore should have been kept within the family. Furthermore, I realized that Katzir, as a participant in the many battles, was hardly in the position to provide an objective account. If they had been endowed with her talent for writing, any of her siblings might have produced a similar story pointing a finger at her.

So I can’t say that this kind of book isn’t for everybody, but certainly that dominant portion of Broken Birds wasn’t for me. I was uncomfortable with the author washing her family linen in public, telling the world about trivial battles that affected no one outside the family and therefore should have been kept within the family. Furthermore, I realized that Katzir, as a participant in the many battles, was hardly in the position to provide an objective account. If they had been endowed with her talent for writing, any of her siblings might have produced a similar story pointing a finger at her.

The underlying premise of the book seems reasonable: that survivors of the Holocaust were, in some cases, so emotionally damaged that it almost guaranteed that their children too would suffer psychological problems. However, I didn’t feel that the author made a crystal-clear case that all this squabbling, back-biting, nastiness, and greed that engulfed the five siblings could be blamed on the parents’ post-Holocaust attitudes. In that most of the conflict occurred in their adulthoods, Katzir and siblings need to turn the mirror of blame upon themselves, no matter how controlling, fearful, and protective their mother may have been towards them.

If I had been the editor of this particular book, I’d have suggested placing far less emphasis on all the battles among the siblings (even though it would have dimmed my friend’s enthusiasm) and expanded two sections of the book that, even in their current state, deserve praise. Katzir very effectively communicates the Holocaust experiences of both her parents, and, additionally writes compellingly of a trip that she and two of her siblings (who stopped feuding for a while) took with their widowed father to his Ukrainian village and later to Germany in an effort to re-trace and to understand the horrific events that had overtaken him.

Those of us who are familiar with the patterns of Holocaust remembrances can see that Katzir retold her parents’ experiences probably as they themselves spoke of them— with some sadness, of course, but without too much dramatization. The father escaped from a chaotic march of concentration camp prisoners near the end of the war by rolling under a railroad car, and then diving into a ditch along the embankment. Katzir helps us see the very same stretch of railroad tracks through her eyes, as well as a barn in which her father had hidden prior to war’s end.

Alas, there had been no similar opportunity for Katzir to visit with her “momila” the forests in which she and other partisans had encamped, committing small acts of sabotage against the Nazi occupiers.

Besides seeing the places of her father’s past, Katzir also met the people who had remained behind in Eastern Europe—the Gypsies who now lived in her father’s amazingly small (to her) childhood home; the Ukrainians who looked upon these visitors from America with suspicion; and Germans who angered Katzir by calling Dachau a “work camp” rather than a “death camp.”

Inmates were executed by firing squad in Dachau’s courtyard, but there were no gas chambers to mechanize and further depersonalize their deaths as there were at Auschwitz. Nevertheless, Dachau’s crematoria were kept busy—over 25,000 people died at that complex, some by execution, but most by disease. A high percentage of the people who went through Dachau were political prisoners, Nazi opponents who were of Christian parentage rather than of Jewish ancestry. Dachau in Germany was a horrific place, but on the scale of barbarity, the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp complex in Poland was even more monstrous.

During this visit to Germany with her father and siblings, Katzir also met an elderly, Christian woman whom her father had dated after the war and before meeting his eventual wife. Can we be surprised that Katzir, so soon after her mother’s death, was non-plussed by the possible rekindling of her father’s romance with this German lady so many decades later?

To my way of thinking, at least, how major events like the Holocaust affect people while it is unfolding and how such events impact upon subsequent generations is a worthwhile subject for a book. What is not so worthy is a treatise on the horrible things five siblings can say and do to each other, nor on which of them deserved more to inherit their mother’s real estate in Los Angeles.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World