By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—It is commonplace to see elementary school classes walking through Cabrillo National Monument on history field trips. But similar field trips to Cabrillo may also be appropriate for high school trigonometry classes – especially for those students who wonder, “What’s the point of this stuff? When would we ever use it?”

Members of the U.S. Army’s 19th Coast Artillery studied their trigonometry because their lives—and the fate of the City of San Diego—depended on it. In the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, soldiers at Fort Rosecrans (which then included Cabrillo National Monument) kept careful watch on the Pacific coastline seeking to protect San Diego against Japanese naval attack.

The perceived danger was not at all far-fetched. An exhibit in a former radio station building at Cabrillo National Monument makes clear that “San Diego was a prime military target.” The city was home to ship repair yards, supply depots, and “served as a principal staging port for troops, supply and naval convoys in the Pacific.” Furthermore, it was home to Consolidated Aircraft which manufactured “B24 bombers, PBY reconnaissance planes and aircraft parts critical to the war effort.”

On the evening of February 23, 1942, “a lone submarine crept close to shore and fired at an oil installation near Santa Barbara, 200 miles north of San Diego,” the exhibit reported. “While the attack caused little damage, the next night jittery troops imagining Japanese aircraft over Los Angeles fired 1,440 rounds at non-existent planes and the morning newspapers reported civilian sightings of Japanese tanks in Malibu Canyon.”

This over-reaction might have been laughable had it not resulted in the U.S. government taking “a drastic and unfortunate step –Americans of Japanese ancestry, many of them enthusiastic patriots, were sent to internment camps for the duration of the war,” the exhibit acknowledged.

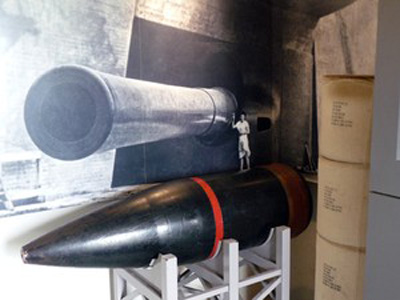

Japan had 72,000-ton battleships like the Yamato and the Musashi with guns that could fire shells 18.1 inches in diameter a distance of 28 miles. In comparison, the United States battleships of the Iowa class displaced only 58,000 tons. Their guns fired 16-inch shells a distance of 20 miles. A 16-inch shell weighed 2,300 pounds, “the equivalent of a small car,” according to the exhibit.

At the beginning of the war, the biggest guns in Fort Rosecrans’ arsenal fired only 8 inch shells with a range of 20 miles—no match for the Japanese battleships should they ever come. Eventually, the United States decided to build for Fort Rosecrans a pair of guns capable of firing 16-inch shells 26 miles—artillery that was equivalent to the guns on the Iowa-class battleships and which were capable of challenging even those of the Yamato and the Musashi.

These two guns measuring 68 feet long were installed in 1944 as Battery Ashburn. The exhibit informs that “at 46 tons a piece they were so heavy that when transported to Point Loma the solid rubber tires of the tractor-trailer carved three-inch ruts into the asphalt roadway.”

Artillerymen had to imagine during practice that an enemy vessel was spotted in motion off the coastline. To determine the target’s exact and predicted locations, the soldiers of the 19th Coast Artillery used triangulation—an important component of trigonometry. At two “base-end stations”—which were a known distance apart—soldiers used an azimuth to determine the angles from their positions to the target. Then, with knowledge of the length of the line AB (the distance between the two stations) and the angles A) and B), the artillerymen could compute the exact distance from the guns to the target. They would take these measurements several times in order to predict the enemy ship’s exact course.

Before aiming the guns, they also would factor in such mathematical variables as wind speed and direction, air temperature, pressure, humidity, muzzle velocity and the ark of the projectile. Spotters would watch the shell fall, and if it failed to score a direct hit on the target, would estimate the distance by which it missed – to be factored into the next shot.

San Diego and Point Loma never came under attack but nevertheless artillerymen occasionally became jittery. Fishing boats were sometimes identified as possible enemy vessels and tracked. And, on occasion, repetitive spray from whales was mistaken for machine gun fire.

Although tensions were high at the beginning of the war, as the United States and its allies began to win more and more battles in the Pacific and advance on the Japanese homeland, tensions on the American mainland eased.

Fort Rosecrans was considered a “good duty station” during the war because the weather was usually nice and it was possible for soldiers to go into town when they were off-duty. When they weren’t reading manuals or less instructive kinds of material, troops amused themselves with baseball games and other athletic activities at Fort Rosecrans, and one group of 19th Coast Artillery soldiers kept a dog named “Red” as a mascot.

Like his masters, Red protected his base from “enemy” attack—but in Red’s case, the enemy was anyone not wearing the uniform of the 19th Coast Artillery who tried to use the latrines in his unit’s barracks. Although the uniforms of U.S. Marine Corps and the U.S. Army were similar, the story is told that Red never failed to distinguish the two – and woe to the Marine who tried to enter the barracks unescorted.

After the war ended, the guns of Battery Ashburn as well as the smaller guns of batteries that surrounded Fort Rosecrans were dismantled and sold for scrap.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. This article appeared previously on examiner.com