By Donald H. Harrison

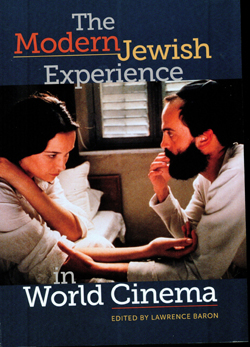

LA JOLLA, California — San Diego State University History Prof. Lawrence Baron was greeted with a full house Wednesday, Feb. 1, at Warwick’s Bookstore for his talk about The Modern Jewish Experience in World Cinema, an anthology he edited of movie analyses by 49 authors, including three from San Diego: himself, Alysssa Goldstein Sepinwall of Cal State San Marcos and Joellyn Zollman who has taught at both SDSU and UCSD.

LA JOLLA, California — San Diego State University History Prof. Lawrence Baron was greeted with a full house Wednesday, Feb. 1, at Warwick’s Bookstore for his talk about The Modern Jewish Experience in World Cinema, an anthology he edited of movie analyses by 49 authors, including three from San Diego: himself, Alysssa Goldstein Sepinwall of Cal State San Marcos and Joellyn Zollman who has taught at both SDSU and UCSD.

Although he had a mild case of laryngitis, Baron followed the entertainment industry’s credo that the “show must go on” with a talk to about 100 attendees that focused on six movies as examples of the Jewish experiences of immigration and acculturation.

Movies depicting the Jewish experience simultaneously express two kinds of history, Baron told his audience: that of the chronological time period that they depict, and that of the era in which they are made. As an example of this, he screened a clip of Tevye, a 1939 Yiddish-language version of the story that a quarter century later would be told in musical theatre as Fiddler on the Roof.

In Tevye, directed by Maurice Schwartz, the daughter who marries outside of the Jewish religion–Chava– gives up her Russian husband Fyedka in order to return to her Jewish home. Not so, in the 1971 movie, in which she remains with Fyedka, and her father shows signs that he’ll someday come to terms with the new world.

In the second selection that Baron showed, the 1922 silent movie Hungry Hearts (directed by E. Mason Hooper) immigrants to America are exploited by their landlord, who raises the rent on their tenement after they fix it up. His reasoning: now it’s worth more. In this movie, the court sides with the landlord, but in a later version, a judge bawls out the landlord for exploiting the tenants.

So stories get changed to reflect the times of their production.

The same process was seen in Israel, Baron lectured. Early Israeli movies reinforced the image of the heroic Zionist pioneer who changes the land, and is changed by the land. The pioneer has to fight the native people — similar to the way American pioneers had to fight movie Indians — only in these movies, the opponents are Arabic speaking.

On the other hand in 1991, said Baron, in an era when Israeli filmmakers were critical of what they considered Zionist myths, a film by Eli Cohen, The Wordmaker, depicted the compiler of modern Hebrew, Eliezer Ben Yehuda, as a fanatic. In the movie, he screams at his wife for daring to sing a lullaby in Yiddish to their son, who at age 4 still isn’t talking. When the argument gets heated, the boy speaks his first words in Hebrew — Aba, lo! (Father! No!).

A different spin on the acculturation process came in the 1967 Soviet film, Commisar, in which a female functionary has become a brutal, seemingly unfeeling person under the communist system. But after becoming pregnant, she is sent to live with a kind Jewish family, who changes her outlook on life and softens her personality.

By the time the movie was made, the Khrushchev era of de-Stalinization was coming to an end, and the film (by Aleksandr Askoldov) was shelved until the time of glasnost and perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev in the final years of the Soviet Union. The film won numerous awards when it was finally released.

The process of acculturation of Jews to Great Britain was depicted in the 1981 British movie Chariots of Fire (directed by Hugh Hudson) in which a Jewish runner and a Scottish evangelical runner (both outsiders at Cambridge) compete with each other. According to Baron, a major theme of this movie was that even though both outsiders were admitted to a first-rate British educational institution, it didn’t mean that they were accepted therein.

The last movie shown by Baron was the 1927 part-silent, part-talkie movie, The Jazz Singer, directed by Alan Crosland and starring Al Jolson. In this film, a boy raised to be a cantor breaks away from Jewish tradition and uses his voice to become a jazz singer, prompting is father to read the son out of the family. But after the father dies, the son returns to his boyhood synagogue to sing Kol Nidre in his father’s place. In his jazz appearances, Jolson wears show business blackface — an act that Baron said has been described as Jews having fun at Blacks’ expense to show that Jews too are white.

Although Baron did not show a clip from Keeping the Faith, a film made in 2000 starring Ben Stiller, he described it as a counterpoint to the Jazz Singer, once again illustrating changing times and perceptions. In this film, the son declines a career in his father’s secular world to become a rabbi. And rather than satirizing blacks, this Jewish character emulates them — bringing a black gospel choir into the synagogue to enliven the services.

Baron’s 441-page book (including index) was published under the Brandeis University Press label by University Press of New England. The paperback version retails for $39.95. The International Book Sellers Number (ISBN) is 978-61168-199-4.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com