By Ira Sharkansky

KIBBUTZ AMIAD, Israel–Our apartment in Jerusalem’s French Hill neighborhood is about 810 meters above sea level. We began our trip to the Galilee by driving to the tunnel under Mt Scopus, and then through the Judean Desert to the Jordan Valley. At the junction to the road north we were 300 meters below sea level, and only about 25 kilometers as crows might fly from home. The road into the valley is good and there is not much traffic. It is not straight down, but low gear is advisable. The road through the valley skirts the Palestinian town of Jericho, where we used to enjoy outdoor meals in the winter and a walk up to the Greek Orthodox monastery of Karantal (Mount of Temptation).

A bit along the valley road we passed the well-filmed site where a Lt Colonel in the IDF ended his career by the non-lethal use of his rifle against a Danish activist who aspired to take part in a pro-Palestinian rally along the road that the IDF ordered closed. The blow echoed through the media of this little place like George Patton’s slap. Our undemonstrative Toyota encountered no problems, either with the Israeli military vehicles or the few Israeli or Palestinian cars we saw for the next 100 kilometers. We passed without incident through the military check point back into what a bit more of the world views as Israel. After the traffic in Tiberius and the twisting climb out of the valley, we reached our home away from home in the guest houses of Kibbutz Amiad. It’s become difficult to find modest accommodations in the Galilee.

Israeli families flood the region on Passover, Sukkot, and weekends, and the providers of bed and breakfast appeal to them with in-room Jacuzzis and other attractions for the kiddies and parents that we don’t want. Kibbutz guest houses remain a modest alternative. Perhaps half the population of the Galilee is Arab, and one of the attractions is tasty co-existence. One test of an ethnic restaurant is a place that attracts ethnic diners as well as cooks. The couple one one side of us spoke Arabic among themselves, and on the other side Hebrew. The food, wine (from a Jewish source on the Golan), coffee, and baklava sent me as close to Paradise as I’ve been in a while. Later we walked off our excess through the Kibbutz, noting once again the modest housing of members, lots of flowers, and decorations by means of old farming and industrial machinery. The subtle message is, “We have been here a long time. It’s our home.”

We had enjoyed the bird songs of late afternoon as we sat outside our room sipping tea, and woke each morning to the bird songs of dawn. Winter rains had been heavier than usual. There were still large areas of snow on the high flanks of Mt Hermon that guided us further north toward Kityat Shemona. In such a Spring as this, the rapids and falls of the Banias were dramatic and load enough to produce a mention of Niagara.

It was not quite Niagara, or even close. However, at lunch at a Lebanese restaurant, at an outdoor table alongside the river the sound was too loud for conversation. Last Fall, perhaps at the same table, the brook was barely bubbly. Only a few meters from the restaurant are remnants of the Greek temple to the god Pan.

From Pan may come the name of the river. Arabic has no “p,” so Pan’s river became the Banias. In the same spirit, native speakers of Arabic are likely to speak with me about “bolitics.” After the wildness of the Banias we went to the calm of the Jordan, encountering groups of Yeshiva bocher on their holiday throughout the month of Nissan. Those we saw were doing their best to act like other Israelis.

Holocaust Memorial Day occurred in the midst of our trip. At home Varda lights memorial candles for the grandmother and uncle she did not know, and watches the programs concerned with the Holocaust until late in the evening. I prefer to internalize my feelings and go to bed early. That is not so feasible in one room on holiday. I was saved by fatigue. When the clerk of the Parks Authority sold us our seniors’ tickets to the falls of the Banias, he asked if we could deal with the 330 stairs. “We’ve done even more than that and survived.” “How long ago?” he asked. Celebration of Jewish history is a major component of what we call Judaism. The list begins with the. Exodus and goes on to the destructions of the First and Second Temples, Chanukah, and lesser ceremonies for one or another disaster in Europe. Now the Holocaust is the major event in what scholars call the “civil religion.” It has begun to penetrate synagogue rituals, except for the ultra-Orthodox who are–as usual– not on the same page.

There are Jews who object to the “Holocaust industry” of organizations that solicit donations for this or that museum, or offer books, pictures, kiddush cups and other items via on-line museum stores. And there is nothing like a visit to the Galilee to remind one of the equivalent “Jesus industry” to serve Christians in need of trinkets. The store at Kfar Nahum (Capernaum) was full of the stuff, along with Christians from several continents. The 10 a.m. two minute siren to mark the Holocaust founded us to pause while walking the Tel Bet Tzeda (Bethesda). Later we heard on the news of two women who had stopped their cars for the ritual of standing alongside while the siren wailed. Not wise on a major highway. The Holocaust claimed two more Jewish victims.

Two of this years televised stories dealt with brothers, now in their 70s, who managed to survive as young children wandering alone. They found homes with Gentile strangers, who gave them Christian names, cared for them for awhile, before passing them on to other families, who gave them different names. The task of one brother, bothered by not knowing who he really was– to find a record of his birth and to learn his parents’ name and his own.

Another program interviewed two 60-something Israelis, who had been born into German Christian families. A man was the child of a low level Nazi official, and a woman the daughter of an officer in the Wehrmacht. Both dealt with their past by converting to Judaism, moving to Israel, and establishing families. We heard a young woman recounting her story of Holocaust days while in school. When her classmates told the story of what happened to their grandparents In Europe, she had to deal with a grandfather in the German army.

We wanted to visit a Druze site, the tomb of the Prophet Jethro, but we could not get beyond the gate due to preparations for the annual pilgrimage.

Dinner was a repeat visit to a restaurant in Rosh Pina that combines good food with the town’s bohemian traditions. It’s history includes art, communes of youngsters who dropped out, and the remnants of the settlers who came a century before the word acquired its present significance.

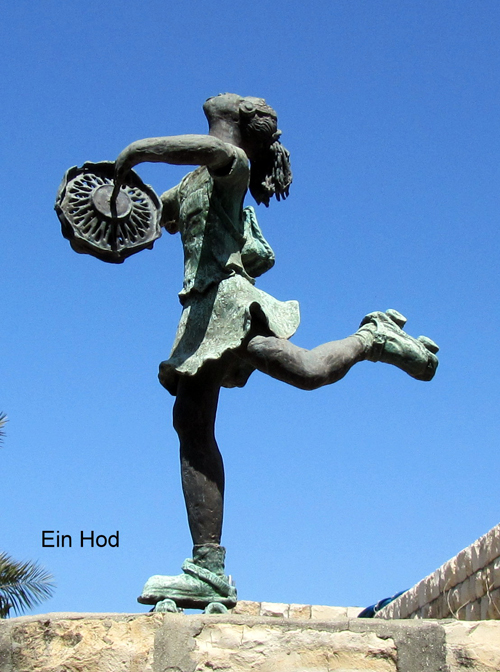

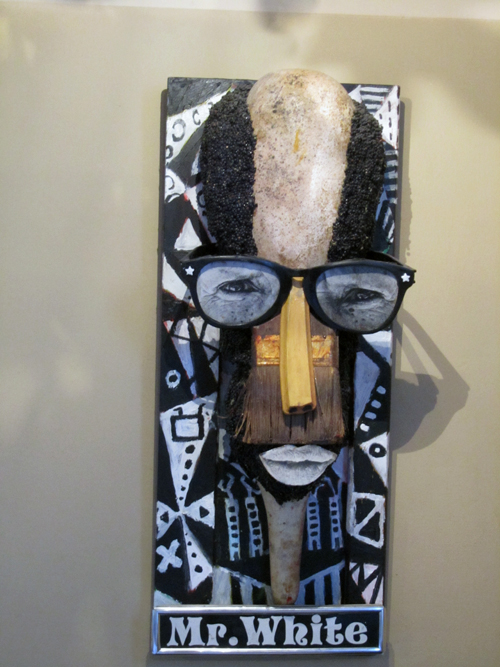

Our route home passed through the Jezreal Valley, climbed a twisting road up Mt Carmel, paused for an hour’s walk through the forest overlooking the city and up the coast to Acco, then lunch with friends in the artists’ village of Ein Hod , dinner with the young couple in Netanya, and a sleep while Varda drove us back up the mountain.