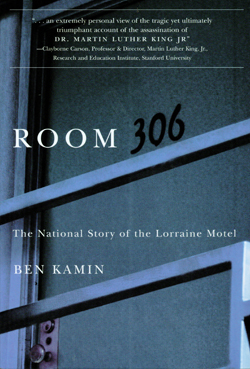

Room 306: The National Story of the Lorraine Motel by Ben Kamin, Michigan State University Press, 2012, ISBN 97801061186-049-8; 186 pages including bibliography, $24.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — As a modern parallel to the ancient Exodus, the march of African-Americans from slavery to freedom has thrilled Rabbi Ben Kamin’s Torah-loving soul. See how he writes about the period following the April 4, 1968 assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., when the Lorraine Motel in Memphis–where the assassination had occurred–was allowed to decay.

SAN DIEGO — As a modern parallel to the ancient Exodus, the march of African-Americans from slavery to freedom has thrilled Rabbi Ben Kamin’s Torah-loving soul. See how he writes about the period following the April 4, 1968 assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., when the Lorraine Motel in Memphis–where the assassination had occurred–was allowed to decay.

“Slave and master, Hebrew and Egyptian, came from the glaring sunlight of America’s national story –all through the oratory, mettle and martyrdom of a modern Moses, and our country at last made a contrite pact with its own ‘manifest destiny’ and supremacist institutions. And this man, for whom postage stamps have been issued, in whose name streets and parks and schools and buildings have been branded, in whose name white housewives, students, priests and rabbis and reverends were brutalized, maimed, or publicly and anonymously snuffed out of existence — this man’s legacy would be allowed to crumble and decompose in and around a little motel on Mulberry Street in Memphis, Tennessee? And no one, no state, no federal agency, no national commission would even raise a hand in defense of this heritage?”

Kamin’s latest book, Room 306: The National Story of the Lorraine Hotel, recounts through interviews with witnesses the tragic events surrounding King’s assassination during his attempt to help black sanitation workers win more humane working conditions. Additionally, through interviews with participants, he relates the story of the successful, though turbulent, campaign to transform what was one of the few motels where African Americans could stay in Memphis into the National Civil Rights Museum beckoning to people of all races.

Rabbi Kamin’s column runs in San Diego Jewish World, a publication emanating from the city he has made his home. San Diegans who know Rabbi Kamin, perhaps more than readers in other parts of the world, may tune into one of Kamin’s self-revelatory passages in which he reports his comments to Beverly Robertson, president and executive director of the National Civil Right Museum, who had been lamenting some of the infighting and pain that had accompanied the museum’s birthing.

Rabbi Kamin told her: “Look, Beverly, I have to tell you. Speaking as just one devotee of the history, as a white guy from San Diego who loves this place and has been mentored by the legacy of Dr. King, there just isn’t that much awareness, if there’s any at all, about this out there, generally. When I have studied the written and video records of the fortieth anniversary of the assassination {in 2008} and all that happened here at that milestone, you saw a fair amount of D’Army Bailey {the first president, who had been ousted from the board}. There were interviews outside Room 306 with him, and he was always dignified, and in many cases he was the face of the museum and was often referred to as ‘the founder of the National Civil Rights Museum.’ But this rancor and this infighting, it’s just not part of what came across.” “‘That’s lovely,’ she said, a bit flatly.”

I was fascinated by how Kamin addressed two author’s issues in the formulation of the book. The first issue concerned the format. Imagine that you’re telling the story of an event. One approach is to relate it chronologically, letting the calendar and the clock provide for you the sequence for the events you wish to narrate. While this approach allows you to bring sharp focus to an event, it nearly forces a writer to discard facts about the interviewee that are tangential to the main story, lest the main point be lost to digression. Quite often some of the rich tapestry of the interviewee’s life regrettably must be omitted.

Somewhere along the line, Kamin decided that the people’s stories, digressions and all, deserved to be recounted, and that required him to take a different approach. Instead of a chronological recitation, he chose to introduce the witnesses and participants one by one, and report their recollections. But this approach, too, has its pitfalls. A lot of the same information had to be tracked over about the events — different people saying essentially the same thing. For some readers, I fear, the repetition may prove wearisome.

The second author’s issue for Kamin was what to do about the Amalekite, the one whose deed was so foul we wish for his name to be blotted out. The realization grew upon me as I read Room 306 that though the assassination was mentioned frequently–how could it not be? — the name of the man who pulled the trigger was being scrupulously avoided. I wondered whether the blotting would be sustained through the entire book, and the answer came on Page 174 in the afterword when Kamin related that the museum now includes items “associated with the accused killer, James Earl Ray…” The museum includes both the motel where King was the target and the rooming house where the assassin found his deadly vantage point.

Enough about writer’s choices. Why should the reader choose this book? Kamin humanizes the story of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., teaching us that a man with fears, faults, and foibles can rise above them and help to refashion not just his own but a nation’s self-conception. And he shows us, through their words, the transformative effect King had both on those who shared in his life and those who studied it.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com