Story and photos by Ilene Lerner

BOSTON– “We are here because the meek shall inherit the earth,” stated Steven Greenberg, the executive director of the Vilna Shul, Boston’s Center for Jewish Culture, as we sat on the Vilna’s front patio. The Vilna Shul is a synagogue museum on the backside of Beacon Hill, and is the only surviving intact synagogue building of the 50 synagogues located in Boston in the 1930’s. I had expected to see the inside of the shul right away, but instead, after greeting me as I climbed the last stair to the old building, Greenberg walked us to a wicker couch and chair on the patio where he indicated we should sit.

(Photos: Ilene Lerner)

As he relaxed into a chair on the patio shaded from the sun by the red brick shul, Greenberg began a narrative. “The story of the Vilna Shul is not only the story of the Jews, it is the story of the neighborhood.” Greenberg directed me to look across the street, pointing at two narrow, four-story brick buildings, noting that they were both over 100 years old. I looked at the now fashionable buildings and could see that they had once been tenements where immigrants and working people had lived – Black, White, Irish, Italian, Jewish, survivors all. I could imagine the people, dressed in the clothes of that era walking in the streets, going to work, the shops, and school speaking Yiddish, Italian, Lithuanian and other languages as they struggled to learn English. I ‘recalled’ how the West End had looked, sounded and smelled because I had been born into a similar immigrant community in the Bronx, N.Y. twenty-five years after the Vilna was built in 1919. At that time the former West End would hardly have been the desirable real estate district that it is today.

As we sat talking about history on that beautiful sunny day, Greenberg began painting a picture of the West End before the city filled in the peninsula, and prior to the arrival of the Jews. Originally, Boston was no more than a two-mile long island, with two major coves. It was connected to the mainland by a narrow neck to the south, now Washington Street. The ocean was to the east and the mosquito-infested Charles River Back Bay to the west. Boston’s earliest settlers first lived on the eastern half of the peninsula in what became known as the North and South Ends, north and south of the cove that they transformed into a harbor. The western half of the peninsula was agricultural. Behind the Vilna, on the other side of the hill, the Boston Common was just that, a common grazing area. Private farms were located north of Beacon Hill in what would become known as Boston’s West End. As early as the 1700’s, a mixed-race, working-class community lived here.

During the Colonial and Federal Eras, 30 percent of the women in Boston were either never married, or widowed, and needed to be their family’s breadwinners because so many men had died at sea aboard merchant and military ships, and as soldiers during Massachusetts’ several wars with Native Americans and Canadians, both French and English. For two hundred years, Boston’s early Puritan town fathers attempted to train these women, many of them single mothers, as textile spinners (spinning wool, cotton, flax, etc., by hand to make thread); thus the term “spinster” became the word for an older unmarried woman.

But as the spinning trade filled up, the unemployed and under-employed women became desperate to find support for themselves and their children in order not to have their children removed by the town. Orphans and children of indigent families too poor to provide for them became wards of the town of Boston, which placed them in the care of farming families in nearby towns. But the women were determined to avoid this fate! “They had lost their husbands,” said Greenberg, “and were not about to lose their children!” The women became prostitutes and set up brothels in the West End. I was impressed that Greenberg spoke of these women with uncomplicated understanding and respect.

Although laws prohibiting prostitution had existed in Puritan Boston since its settlement in 1630, Boston Puritans did not have the financial resources to enforce those laws. If mothers were unable to provide for their children or were arrested, their children, now wards of the town of Boston, would burden the treasury. Boston’s town fathers chose to ignore the prostitution, which became a thriving trade in the West End. The area became known as ‘Mount Whoredom’, a jab, Greenberg explained, “as much at the monarchy as at the world’s oldest profession.”

The West End neighborhood, located next to the mosquito-infested Back Bay swamp, and featuring a lively Red Light District was of little interest to Boston’s wealthy, (although it was where they put its hospital, Massachusetts General, and its jail, now, the Liberty Hotel). However, it was very attractive to Boston’s immigrants, Blacks, and working class in the mid and late 1800s, offering housing “at the most affordable rents.”

The first Jew recorded to have arrived in Boston was in the 1600’s, but it was not until two hundred years later that a large migration from Eastern Europe came to the East Coast. As the cities of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania filled with immigrants, jobs and housing became easier to find in Boston, first in the North End, then in the West End. Jews, along with Irish and Italians, began arriving and settling in the two neighborhoods during the 1800’s.

When I expressed surprise that Jews would move to an area where prostitutes lived and worked, Greenberg explained that while houses of prostitution still existed, their business was conducted behind closed doors “and was not obvious to the community.” He added, “The prostitutes, wanting, at all costs, to avoid causing irritation to the authorities, employed bouncers to toss out or otherwise ‘take care of’ troublesome clients, and to protect the West Enders, providing one of the safest working class neighborhoods in Boston.”

The Vilna Congregation was founded in 1893. It met for 14 years in congregants’ homes and empty storefronts until 1906 when the Lithuanian immigrants purchased the vacated Black Twelfth Baptist Church building at 45 Phillips Street. With dirt poor immigrant Jews and other immigrants moving into the neighborhood, the slightly more affluent Blacks moved out to better neighborhoods, and at least three West End Black churches were sold to newly founded Jewish congregations (including the nearby African Meeting House, which had also hosted the most well attended Abolitionist rallies). Religious services and ceremonies were held at the Twelfth Baptist for 10 years “until the city took the property in 1916 by eminent domain to enlarge the Phillips School.”

The congregation then met for three years at the nearby Anderson Street Hotel; and in 1919, the Vilna bought property a block away at 14-16-18 Phillips Street, leveled the three tenement houses on the site, and built the present L-shaped Vilna Shul. The red brick Shul served the religious, spiritual and community needs of the Orthodox Jews of the West End for six decades, until 1985.

After the First World War, the United States put severe restrictions on all immigration from Europe, ending the stream of Jews seeking housing in the West End. Boston’s Jews went to college, got better jobs and moved to areas with more housing options, as the old West End buildings were cut up into smaller and smaller units. In the seventies, the West End was facing the prospect of Urban Renewal that would destroy much of the community.

In 1985, after 60 years of service and in deplorable condition, the last member, Mendel Miller, held a lonely service, locked the Vilna’s doors and gate and closed the Vilna Shul. The Vilna community had moved to Roxbury, Mattapan, Dorchester, Chelsea, Brighton and other communities. According to Greenberg, the 93-year-old synagogue building owes its improbable survival, initially, to its undesirability as a property; later, to the tenaciousness of Mendel Miller, the last member and president of the Shul who refused to sell it for years; and currently, to it being a revered and protected historic site in a treasured historic neighborhood.

Finally convinced the shul building should be sold, and with a potential buyer who wanted to build a parking lot, Vilna President Mendel Miller, appeared at court in 1988 to dissolve the shul’s legal corporation. When the judge learned that the Vilna Corporation had less than the three required members, he found the corporation to have expired, the property and its contents without an owner, and the court placed it all into receivership. During years of litigation, homeless people and pigeons lived in the Vilna, and the building suffered leaks that almost destroyed the building. Realizing that the property was in jeopardy, Jews and non-Jews, members of the historic and preservation community came together. The Vilna Shul, Boston’s Center for Jewish Culture, organized in 1991 to rescue the building, preserve the history and continue its legacy, was awarded the property and contents in 1995.

With the Vilna Shul in somewhat better condition in 2001, Aaron Mandel and Andrew Perlman climbed over the fence around the Vilna’s patio, pulled off some boards and managed to gain entry. They thought it would make a good place for their Havurah prayer services. The Havurah on the Hill, as they named themselves, still meets one Friday night a month and for the High Holidays.

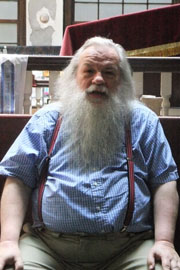

At this point Mark Nystedt, a bearded volunteer with long white hair who looks like a Torah patriarch, joined us on the patio. He soon revealed he was not Jewish, but had a great interest in history and research. “I wandered in one day in 2005 and have been here ever since.” Greenberg told me that Nystedt would now give me a tour of the shul. We entered and climbed a flight of stairs on the left. A huge round stained window featuring the Star of David presided importantly over the lobby at the top of the stairs.

I entered the sanctuary and saw a nineteenth century synagogue, observing that despite its age and obvious need of restoration and repair, it looked similar to Orthodox synagogues of previous and current generations. But it was also unique. In the middle of the large room were two huge skylights: bright sunshine filled the sanctuary. Surprised, I asked Nystedt if skylights were common in synagogues of that era. He answered, “They were common in factories.”

As I looked next at the electrified gas crystal chandelier hanging from the ceiling, my eyes lingered on a surprisingly large crystal Star of David with light bulbs attached to its points. Nystedt said at some point electricity had replaced the earlier gaslights. I turned to the tall windows topped with stained glass, the ark containing the Torah, the Ten Commandments on the Ark, the two marble plaques with the membership roll of the congregation carved in Yiddish and English, all with Hebrew letters, on a wall. I felt moved by the consciousness of an unbroken history of Jewish life. As I walked around the sanctuary, taking photos from different perspectives, I could see the synagogue filled with people at countless weddings, bar-mitzvahs, funerals, religious celebrations and ceremonies. How sad it must have been for Mendel Miller to see the congregation to steadily dwindle to one!

Nystedt sat on a pew and gestured for me to sit opposite him. After I was seated, he informed me that these wooden, high-backed pews had come from the converted Twelfth Baptist Church where members of the Civil War Union Army’s Black 54th Regiment, (made famous by the movie “Glory,”) had once worshipped. “You might be sitting on a pew that a 54th Regiment volunteer sat on,” suggested Nystedt. “Wow!” I responded; and with a twinkle in his eye, Nystedt, agreed, “Yes, Wow!” He then showed me the ends of the pews where the arms of the large crosses that had decorated the pews had been removed when the church was converted to a synagogue.

Looking up again, I realized that the Vilna lacked the traditional balcony where the women, their hair covered by kerchiefs, would sit. I asked Nystedt, “Where did the women sit?” He indicated the pews behind me in an adjacent area. The rabbi had stood in the elbow of the L-shaped room, on the platform bimah, clearly visible and audible to both sections of the congregation, the men in front, and the women to the left.

“How many members did the shul have in its heyday?” I asked. While pointing at marble plaques listing the Vilna’s membership, Nystedt answered, “One hundred and twenty official male members, and one hundred and twenty in the Ladies Auxiliary.” “The ladies weren’t even official members!” I exclaimed! I remembered my mother telling me how her brothers were sent to the Orthodox synagogue for religious instruction while she and her sisters learned what they could of Judaism at home and in the community, only being expected to cook, clean, wash and iron the family’s clothes. A Jewish education was for men only, and women were second-class citizens in the shul, separated from the men during worship services. Years ago, as a child, I had felt marginalized sitting with the women in the balcony, as I watched the men below conducting the services. As if further testimony were needed, in the front of the sanctuary, under the windows, was an exhibit of quilt squares honoring strong Jewish women, made by Jewish women, testifying to changing values regarding the role of women.

Grants from philanthropies and foundations have aided the restoration effort; and the partial uncovering of three different period murals (underneath an overcoat of beige paint) has excited interest. But much more money is needed to restore the murals and the synagogue. Today the shul offers young Jewish professionals and older retirees, who are returning to the city, speakers’ series, prayer services and community events. It appeals to both secular Jews as well as the religious, and continues to attract visitors and tourists.

As Nystedt and I were finishing our tour, an Irish mother and her adult son from Belfast joined us in the first floor exhibit space. I asked them what had brought them to the Vilna on their first visit to Boston. The son responded that he lived in Belfast where there were “probably about ten Jews”, but he had met one and gotten along well with her. Since then, he had met more Jews and always had a good rapport with them. We agreed the Irish and Jewish sense of humor go well together. Now, whenever the son travels somewhere, he always makes sure to visit sites of Jewish culture and life. Mark Nystedt concluded, “Half of my enjoyment here is in conducting tours and explaining the history to non-Jews.”

As I left the shul, I reflected that people from other countries had been visiting the Vilna for years, yet this vital piece of Jewish history had been completely invisible to me for the 40 years I have lived in Massachusetts. Although I am a member of the African American Museum, just a few streets away, I had been ignorant of the Vilna Shul! I turned around and looked back at the shul from across the narrow old street, thinking about how the history of Boston’s Jews and Blacks was intertwined, and this simple building represented one link in that important story also. I stood there a few minutes rejoicing that the Vilna Shul, this last of Boston’s immigrant synagogues, like the Jewish people, still survives today.

*

Lerner, a freelance writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, may be contacted at ilene.lerner@sdjewishworld.com

What a nice article! I live across the street from the Vilna Shul and I love it. It is such a gem in our neighborhood.

I know all about the Vilna Shul. I grew up on the hill. My grandparents were active in the Shul and he was president of the Shul in the 1950s. All that is left of us that prayed at the Shul is my aunt who turns 100 years young in September, her brother, my brother and myself.

Vivian (Getz) Fleitman