Third in a Series

Story and photos by Donald H. Harrison

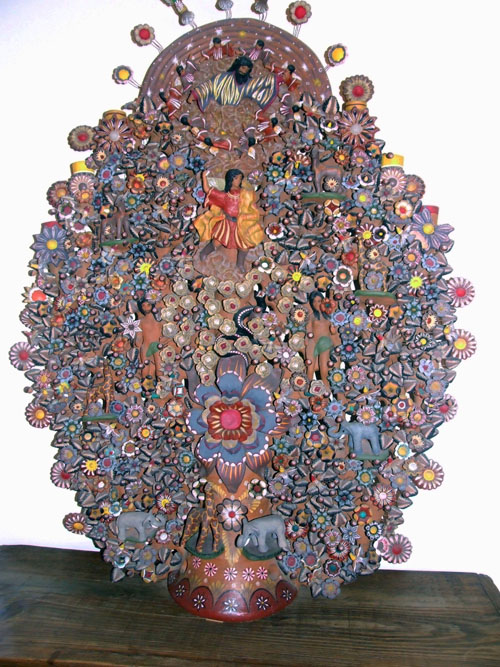

TECATE, Mexico — Looking at a ceramic ‘Tree of Life’ in the gift shop of Rancho La Puerta, I discerned that it depicted Noah on his Ark. In the Administration Building was another ‘Tree of Life,’ this one picturing God, the Archangel Michael, and Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. And in the Dining Hall, there was what might be called a “Finding Nemo” Tree of Life and, not as paradoxical as it sounds, a “Day of the Dead” Tree of Life as well.

Jennifer Brandt, artist-in-residence at Rancho La Puerta, escorted me on an art tour that included sculptures by Francisco Zuniga and other Mexican sculptors who were influenced by him; stained glass windows and iron works by James Hubbell; and a carmine dye such as that used by Rembrandt in the portrait of “The Jewish Bride.” The dye was created by a cochineal, an insect that she plucked off a cactus.

A major portion of the tour dealt with the folk art of Mexico, helping me to make sense of the riot of color and the seeming chaos of the various “Trees of Life.” As a point of clarification for my fellow Jews, I should note that notwithstanding the allusions to two stories appearing early in the Book of Genesis, “Tree of Life” does not symbolize the Torah to which a synagogue song urges us to hold onto fast, but rather it refers to an element in the cosmology of indigenous Mexican peoples prior to being conquered by the Spaniards. The term did, however, stimulate my curiosity.

Brandt explained that before the conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico in the 16th century, a phrase in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, that was equivalent to “our father,” referred not to God above, nor to a human progenitor, but to a tree in a creation story upon which all manner of life grew. The tree, literally, was a “tree of life”–giving sustenance to human beings, to animals and to other kinds of plants.

Under the influence of Jesuit missionaries, the tree-of-life concept was adapted by artisans in southern Mexico to illustrate many stories of Judeo-Christian origin. Subsequently the Tree of Life format grew according to the folk artists’ imagination. These ceramic “story boards” sometimes were decorative in function, designed to sit on a mantle or a table somewhere, or sometimes were carried in processions to celebrate various Mexican holidays and feast days of Catholic saints. In the latter case, candle holders and incense burners often were built right into the design of the symbolic trees.

The Garden of Eden Tree of Life (above),features God the Father up on top, Michael the Archangel, Adam and Eve in the branches, the serpent, and other animals in “a very Old Testament kind of feel,” Brandt said. In variations on the theme, the stories depicted may be Noah’s Ark, or Jonah and the large fish that swallowed him.

Analyzing what she referred to as the “Finding Nemo” Tree of Life, so nicknamed for the very popular, animated, 2003 movie about a father clownfish braving the dangers of the ocean to find his son, Brandt commented that to untrained eyes, “this is so chaotic and so right-brained (creative) that with our very left-brained (logical) cells, we are overwhelmed initially. But I think all that is really required to suck the juice out of these pieces is to stand in front of them for about 10 minutes and just look and give them your attention. After a very short time, things start to jump out.”

She said the marine Tree of Life “is very contemporary except when you look at the mother and child mermaid. She is wearing a crown so this tells you who they actually are. This is the Madonna and Child being recast as mermaids” and with them “are the attendant agents.” This particular Tree of Life is “very bilaterally symmetrical. You can tell that the small pieces were pressed into molds.”

Brandt noted that “none of this was done by machine. All this is the work of human hands, one family, and very often four generations of one family, working together around one table.” In the United States, she said, it is often assumed that one either has the “artistic gene” or not, but in Mexico, the ability to make art in many cases is considered a standard human attribute. “If you marry into that family, no one says, ‘Okay show us where your artistic skill is.’ It is assumed that everyone has this, it is something that you get when you get a body– the impulse to make beautiful things. So you are given a seat at the table and ‘today we are making fish.'”

If you look above the central figure, the mermaid representing the Madonna, you can see little berries. “It took me a while to figure why these are on almost all Trees of Life, and while I was watching the work being done, I suddenly realized, ‘oh this is what four-year-olds can do,'” Brandt said. “This is like the first task of every little person in a ceramicist’s family: to learn to roll little balls of clay. And these are incorporated into the design.”

The base, which can be seen from the back, is typically designed by one of the elders of the family. “Then they put it outside and let it dry until it hardens. “It is sort of like the Goldilocks story ,” in which the visiting little girl wants the temperature of her porridge to be just right. “It has to be dry enough that when you push a wire in, it doesn’t just fall out when you put some weight on it, but not so dry that it won’t accept the wire,” Brandt explained. “While that is drying, all these tiny pieces are pressed into two-part molds, and also put out in the sun to dry.” Then when it is all at the right point, they stick the wire into the piece and the other end of the wire into the base “and then it goes into a homemade, backyard, wood-burning kiln, very often really rudimentary. Then it comes out. There is about a 20 percent explosion rate in the kiln, a pretty high rate of attrition, but what can you do? It is the nature of the beast. They do a little fixing–sometimes they send it in for a second firing–and then it comes out and it is painted with an acrylic paint developed in Mexico in the 1950s. It is a paint that will have this color forever, and this is the pallet of Mexico. There is a world of color here.”

The figurines may be moved out of the way on their wires to permit painting of the creation — and “this is an epic, incredible amount of work,” Brandt said.

Brandt walked from the marine Tree of Life to the one invoking Mexico’s celebration of the Day of the Dead. To understand the piece, she said, one must have an appreciation of the contrasts between Halloween, as it is known in the United States and other countries in northern latitudes, and Mexico’s Day-of-the Dead celebration.

Halloween, she said, occurs on Oct 31 at that time in the northern latitudes “when it seems as if the earth is dying, the year is dying, light is draining out of the sky more and more every day, the trees are bare, and everything looks dead. Human thought turns to our own impermanence.” In various western traditions, Death is pictures as the Grim Reaper, a male skeleton who carries a scythe, the idea being that “death whacks you off at the ankles to take you off to hell presumably, so death is the harvester of humanity,” Brandt said. “There is a secretive malevolence about him.”

“The dead of Halloween are malevolent and scary,” Brandt continued. “The dead are walking among us this night that the veil between the world of the living and the dead is so thin and porous. This night it is passable. The dead slip into our world, and it is a very dangerous night, so the Celts believe, to be on the street in case the dead see you. Because if they see you they will hate you and be jealous and they will retaliate. So, God forbid, if you were seen on the street, you dressed as one of them. That is why until the 1930s, your only choice of costume were ghost, ghoul, witch, goblin, something spooky.”

Brandt said that the holiday began changing during the Depression when municipalities decided to take back their streets from vandals and other ne’er do wells who were setting buildings on fire, and trashing cars and causing other destruction. Halloween was transformed into a family holiday, with children dressing up in all sorts of costumes, from super heroes to nurse, and people eventually forgetting the holiday’s origins.”

In Mexico, the Day of the Dead actually stretches over three days. The first, coinciding with Halloween, is for children who died. The second day, Nov. 1, is for people who did not die natural deaths. And the third day, Nov. 2, the most festive, is for everyone else. “It is a totally different idea,” said Brandt. “The dead are not some strangers, they are your dead. They are waiting all year for the chance to come visit. So Day-of-the-Dead is an invitation to the dead, your dead, your parents and grandparents, anyone you loved and lost, to come home. So it is the big party that happens in the cemetery that to Americans is freakish and crazy — you bring food, and booze, and love and prayer, candlelight, and mariachis into the cemetery. You wake them up. You bring armloads of marigold flowers, which is a new-world flower that the Aztecs considered the flower of the dead, literally. You pluck the petals and you leave them as a trail for the dead to follow. It is interesting that the petal of the plant becomes the seed of the next generation, so imagine the number of repetitions from one grave to the cemetery fence. You eventually sow a living path which comes back every year at that time.”

The dead follow their families home from the cemetery and “candles are lit in the pathways going up to people’s front doors.” Brandt said. “There is a tradition that you put a bowl of keys in the doorway, in case the door is accidentally locked, so that the dead can come in.”

Knowing this is essential to appreciating the “Day of the Dead” Tree of Life, in which the central figure is not a male Grim Reaper, but an elderly woman known as Katrina. (The symbolism of calling the great hurricane of 2005 by this name was not lost on the Mexicans).

Unlike the vicious Grim Reaper, “Katrina is a party girl,” Brandt says. Her figure on the Tree of Life demonstrates a “hilarious whimsy. She is kind of sexy, but at the same time she is ridiculous and funny, showing a bunch of femur (instead of a fleshy leg), or the deep plunging cleavage revealing sternum,” Brandt said.

“There is something intimate about this figure, grandmotherly almost. She is dressed in the clothing of a time gone by, so you have the sense of an older woman who might, once you died, take you by the hand and walk you across — as opposed to the reaper who might cut you out of the field and drag you to hell.” Katrina’s origin “is much more recent than you might think . About 1910, during the Revolution in Mexico, she was the creation of a specific artist, Jose Guadalupe Posada, (who) made her as a political cartoon. He dressed her in the garb of the landed aristocracy of Mexico clinging to a certain colonial fabulousness which did not reflect the extreme poverty of everyone else” nor the coming land distribution.

“By dressing her in the style of the past, she was a wealthy landed woman. By making her dead, the political commentary was that ‘you people don’t know it yet, but you are dead, you are already dead.’ After the revolution she was embraced. She became one of the great icons of the country. She has a husband, and you see these well-dressed dead together very often, you see them sometimes walking a little skeleton dog.”

Unlike the “Finding Nemo” Tree of Life, the “Day of the Dead” tree is “not bilaterally symmetrical,” noted Brandt. “There is one thing going on over on the left or life side, and there is another thing going on over on the right, or death side. On the life side, here in Mexico, even though it is not Africa, the big five game animals represent life on earth–they include lions, giraffes and elephants — and if you look, they are two by two. And if you notice, the sun flower, the symbol of life, appears on both sides. The calla lily, a symbol of the eternal cycle, a perennial that comes back year after year, also is on both sides of the tree of life, so in a way this is a visual depiction of the fact that you cannot have one without the other. You cannot extract life and have it separate from death.

“Part of the visual of this is the balance between life and death. I think death is what messes us up in the U.S. We think if we take the right classes and think the right thoughts, and get plastic surgery, we can avoid the whole thing. In some ways, I think it is a first-world versus a third-world question. A few months ago I was driving through town (Tecate) and there was traffic–which is unusual in this one-horse town — and I realized that I was behind a funeral. I had no idea it was a funeral because the coffin was in the back of a pick-up truck, with about 20 people in the back too, and they were singing, celebrating in a way that would not be in our world.”

In the Celtic idea of Halloween, candy is distributed as a “bribe” to the dead:” take this, go away, go next door, kill someone else, here’s some candy, move along,” Brandt said.

“Here in Mexico there is the same idea that the dead have a sweet tooth. I think it is metaphorical that what they really long for is the sweetness of having a body, a life. They like bananas and they like pan de muerto — the bread of the dead — which is a sugary, orangey, delicious bread. You build an altar in your home that has an arch of sugar cane on it, and on that altar you put fruit, flowers, candles, sugar skulls, photographs of the dead; things that they touched, their favorite jewelry or hobby — anything to make a welcoming space for them so that they will want to come to visit — it is just lovely.”

The sugar skulls, seen on the death side of the Tree of Life, are reminiscent of “Valentine’s Day, Easter and Halloween rolled into one,” said Brandt. “You go to the pastry store. You order your sugar skull, tell them you like orange, or pink, or birds or whatever, and they decorate the sugar skull. Flowers on a vine perhaps climbing into the empty eye sockets, birds in flight across the cheek bones in icing. You come to pick it up. You tell them the name of your sweetheart and they write the name across the forehead of the skull and you give it to your beloved on the Day of the Dead. ‘Happy Death! Here’s what is coming, the one thing that we all share.'”

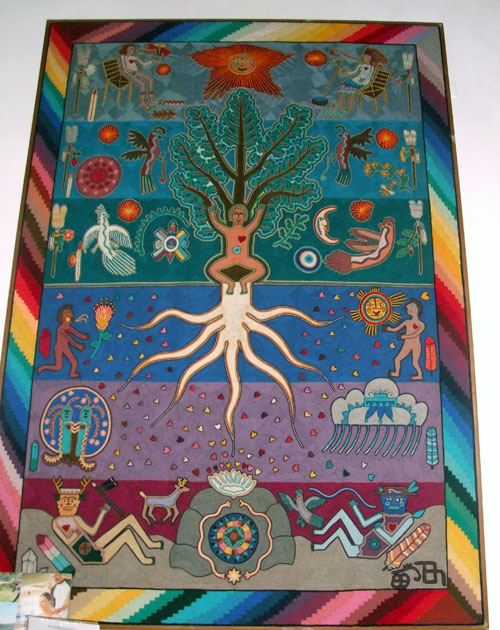

The Day of the Dead finds artistic expression not only in ceramic Trees of Life, but in other art forms as well, including yarn painting, which visiting artist Timothy Hinchliff demonstrated for Rancho La Puerta guests.

Originated by the Huitchal Indians, who live in the Tecate area and a little south, a yarn art Tree of Life looks like a tapestry “but under this is a piece of plywood that has tree sap that is troweled on, very, very sticky. Then a continuous yarn is taken out of the skein and pressed into the wax, and tracked back against itself a zillion times.”

Although Hinchliff uses a Huitchal technique, his yarn art looks quite different from the art of the Huitchal. “It is not a matter of better or worse, but it is an interesting way to see the cultural differences in a very visual and coherent sort of way,” Brandt said.

“You look at this and this has a very left-brained approach, the linear nature of line-by-line progression, top to bottom, bottom to top. Also the fact that there is something dead center (a human figure as the center of the Tree of Life), and objects radiating out of the center. Each one has the same amount of negative space around it. Here’s a heart, here’s a man, this is a very left-brained, very American lens.

“If you go the Huitchal originals, they are strikingly different. For one thing they are completely non-linear. Everything emerges from another form. There is a chaotic filling of negative space (much like the ‘Finding Nemo’ Tree of Life). There is no respite for the eye to relax and rest. Initially it is chaos, crazy.

“It is a fascinating way to get a sense of how our culture dictates how our minds work.”

*

Next: Part Four, Currying the guests’ favor with Indian cooking

*

Harrison, editor of San Diego Jewish World, seeks Jewish-interest stories wherever he goes. His wife Nancy is an agent with Avoya Travel/ American Express, who’ll be happy to answer questions about Rancho La Puerta accommodations and reservations at (800) 786 3265, or (619) 265-2909, or via nancy.harrison@avoyatravel.com

This article captures the exuberance, joy and meaning of this folk art. Day of the Dead is celebrated every year in Tecate at Parque del Profesor. It is a wonderful experience with dance, theater, many traditionally decorated altars and food.

Wow! I’m impressed.