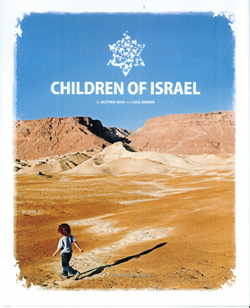

Aletha Gold and Luca Zordan, Children of Israel, Gefen Publishing House, 2013, ISBN 9789652296238; 191 pages.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Here is a photo book portraying the multi-ethnic character of Israel while expressing the wish that the children pictured can grow up together in peace. It is a volume with voluminous purposes: to acquaint the people of the world with the Israel they do not often encounter in the headlines, to promote tourism throughout the country, and to spread hope.

Australian writer Aletha Gold and Italian photographer Luca Zordan are so committed to these causes–and to Israel–that they are donating the proceeds from this 191-page photo essay to an organization for the absorption of Ethiopian immigrants to Israel.

How foreigners see a culture is, of course, interesting, but there is a difference between those who retire to subsidized hotel rooms each night, as Gold and Zordan did, and someone who lives among his or her subjects. I asked Art Prof. Paul Turounet, chair of Visual Arts and Humanities at Grossmont College and a photographer who immerses himself in the lives of his subjects, to look Children of Israel over and to share his reactions with me. Turounet has won accolades for his study of the risks that undocumented migrants take when they attempt to slip across the border into the United States. He portrayed their experience by journeying with them. .

As he looked through the book, Turounet pronounced himself far more interested in the single-subject portrait shots, from the waist or shoulders up, than in some of the photographs picturing children at play or at other activities. “The portraits are more piercing for me,” he said. “I think people are interested in psychology and emotion.”

Many of the photographs in the book have the children smiling as they look at the camera, and these Turounet passed by quickly, explaining that while sometimes such a posed shot is appropriate “because it forces the viewer to have direct contact, eye-to-eye, with the subject, and that can produce psychology and discourse” very often such an approach “feels a little forced.”

He explained: “The smiling kids–some come off as genuine–but adults have a tendency to say ‘smile for the camera’ which makes you wonder if that is really how kids feel at the time?”

So, it was the portraits in which the children were looking off camera where Turounet’s gaze naturally lingered. For example, there is an Ethiopian boy in profile and in orange shirt and colorful kippah staring off to the photographer’s left. He is in sharp focus while the barren landscape behind him is out of focus, and you can almost hear him wonder what it is exactly that he is looking at. Another image is of a boy in Pardes Hanna at a school for children at risk because of abuse or violence in their homes. The boy’s blond locks cascade below his white and blue kippah, a care-free hair style that contrasts with the pensive expression on his face.

Another engaging shot, is of a three-year old boy with shoulder length hair. He is wearing a dress shirt, and in a few minutes he will have his first haircut–or upsherin–and it is clear, as he looks off camera, that he’s not looking forward to the occasion.

Turounet was particularly engaged by the shot of a Circassian child, dressed in that ethnic group’s folkloric costume. The little girl is looking up at somebody, slightly to the left of the photographer, and what she is thinking is a mystery. Her red, white and gold costume, with long silken scarves flowing from a pillbox hat, are not the kind of images one typically associates with Israel. The Circassians are Sunni Muslims who after being displaced from Russia resettled in the Middle East, and now form a community of 4,000 centered in the Galilee region of Israel.

The art professor lingered again near the end of the book over a photograph of three girls running through a wheat field, each holding up a single stalk. They are having a great time, and the photographer stationed somewhere near them for an instant has been forgotten. “Oh this is a nice picture,” Turounet said. “This is a book that is definitely educational, embracing the joys of life, there is no doubt about that.”

Turounet has never been to Israel, but he has formed impressions. “My girlfriend is of Jewish heritage. I am of French heritage, Catholic, and I have Palestinian friends,” he said. “Anytime I see something like this I want to see it from my own eyes, see what it is all about.”

He expressed the wish that the photographs could have been more candid, more like those made last century of children in the streets of New York by Helen Leavitt, or those of children of pre-Holocaust Europe, immortalized by Roman Vishniac.

Turounet’s overall impression of Children of Israel: “Although there is joy, there is also a layer of sadness to it– a veil of sadness–that speaks to me about a desire to get back to the simple things of life and a peaceful existence. Politics, history, memory interfere with that. It is almost as if people are at the stage where they are very conscious of having lost hope.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com