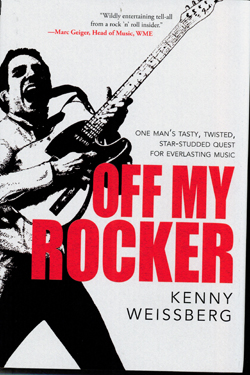

Kenny Weissberg, Off My Rocker, Sandra Jonas Publishing House, 2013, ISBN 9780985581565, $26.95, 305 pages.

SAN DIEGO– For more than two decades Kenny Weissberg was the concert promoter who brought to Humphrey’s By the Bay an eclectic mix of talent, some being big names in the music industry, and others who never lived up to their promise. Weissberg also worked as a disc jockey on various radio stations around town, with corporate takeovers typically forcing him to end his gig at one station and move his independent brand of music appreciation to another.

In Off My Rocker, Weissberg tells the story of his early life quest for sex, drugs and rock n’ roll and assures us that he later kicked the cocaine habit, married and stayed faithful to his wife, and therefore was able to devote almost all his energies to advancing the cause of good music in various genres.

Although we read about his interactions with numerous music stars including Joan Baez, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, Ray Charles, B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Dionne Warwick, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, and Whitney Houston as well as with comedians such as Gallagher and Roseanne Barr, one of the more memorable personages in this book is Robert Bartell, an owner of the Bartell family’s chain of properties that includes Humphrey’s on Shelter Island.

Perhaps that is because Weissberg only met the recording stars and comedians in the context of their performances at Humphrey’s. He tells stories about some of their more interesting demands — for example, a room without carpets for James Brown, who worried about static electricity messing up his hair. However, Weissberg really didn’t get to go below the surface with any of these stars — their encounters being too brief– so what we get are a series of anecdotes, rather than very deep insights.

Bartell, on the other hand, was Weissberg’s boss, with whom he had a long working relationship. Although Weissberg didn’t use this term, Bartell was a “square” who didn’t really understand the music business. As far as he was concerned, everything should be done by the book. You negotiate a price for an act, pay the fee, promote the act, the act performs, and everyone goes home happy and with a little profit. Bartell didn’t like the idea of providing inducements to agents and managers in the form of gifts, tickets, complimentary passes and the like to encourage them to keep sending the good acts to Humphrey’s. So, without Bartell’s knowledge, Weissberg created a little slush fund by selling unused complimentary tickets to latecomers to the concerts. He says he used the cash so derived to keep providing such goodies for the decision makers. However, an accountant eventually found the discrepancy, prompting Bartell to fire Weissberg.

Devastated, Weissberg mounted a campaign to get his job back, getting the movers and shakers in the business to write and call Bartell in his behalf. He contended that every dollar he diverted for such purposes were to build the business and not for his personal use. Bartell eventually relented, taking Weissberg back for another 15 years. When Weissberg finally did leave in 2006, after 23 years with Humphrey’s, he reports it was because concert promotion had lost its luster for him. In his learned opinion, concert promotion today is a money-driven business in which everyone–the managers, the artists, the venues–chase profits and no one has loyalty to any other person or idea. So he simply had enough.

In describing Bartell, Weissberg noted that the family business was responsible for seven hotels and one thousand employees. Richard Bartell, he wrote, “was meticulous and honest and had seemingly bottomless pockets. Deposits went out like clockwork, vendors got paid on the day of the show, and he agreed with my recommendations that he pour a small fortune into upgrading the venue, doubling its capacity in the process.”

From Weissberg’s point of view, Bartell’s shortcoming was in having no interest whatsoever in helping young talent along. He was only interested in booking acts that were already proven. He wanted Weissberg to focus on Humphrey’s bottom line, and not try to be someone’s mentor.

When Weissberg deviated from this formula, “I have little doubt that he would have fired me if we hadn’t been making so much money.”

Although Weissberg makes reference to his Jewish upbringing from time to time, this is a part of his life that is not well-represented in the book. He shares little about what Jewish values–if any– helped inform his life’s decision. He does not disclose any involvement with the local Jewish community. Throughout the time span covered in this memoir, his affiliation–in fact his identity–remained fully with the music industry.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Pingback: Concert promoter shares music anecdotes in memoir | Tickets for you