By Donald H. Harrison

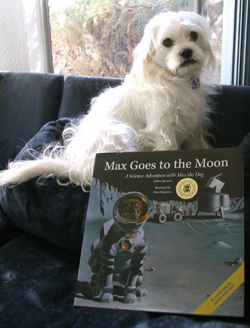

SAN DIEGO– It is too bad that our dog Benji can’t read, because if he could, Max, the Rotweiler who is the hero in four books of space adventures, might become one of Benji’s favorite characters in literature.

In a series of four stories by San Diego-raised, University of Colorado astronomy professor Jeffrey Bennett, Max visits the Space Station, the Moon, Mars, and Jupiter. While the stories, themselves, are easy for elementary school students to follow, they are accompanied by side panels that anticipate some of the questions about science that children might ask. By referring to these information boxes, parents who are not themselves scientifically trained can answer many dozens of questions like “Why are astronauts weightless?” or “How do you tell time in space?”

Not only parents, but older children as well, may peruse the side panels to learn the “real science” behind Max’s fictional adventures, so this truly is a series of books intended for readers of different ages. The series has been honored with awards from the American Institute of Physics and the International Reading Association, among other organizations.

In a recent telephone interview, Bennett told me that as a teenager growing up in San Diego, he was inspired to teach by Helene Schlafman, educational director at Congregation Beth Israel’s religious school. According to that congregation’s sesquicentennial history book, Schlafman started what is believed to have been the first-in-the-country madrichim program in which teens were trained as assistant teachers. They learned leadership techniques, child development and group dynamics as part of the “mad” program at the Reform congregation.

Bennett went on to become a teacher’s aide at Sunset View Elementary School in San Diego while obtaining a bachelor’s degree in biophysics at UCSD, where he graduated magna cum laude. From there he transferred to the University of Colorado, where he obtained his master’s and doctoral degrees in Astrophysical, Planetary, and Atmospheric Sciences, and soon joined the faculty.

Bennett’s mother Tamara wrote a selection that was published in a book commemorating Hadassah’s recent 100th birthday, so evidently the writing gene runs within his family. Long before he started on the fictional series about Max, Bennett authored textbooks on mathematics, astronomy, statistics and astrobiology. “I have those four subject areas and those books are all in multiple editions,” Bennett told me.

Bennett said back in the 1970s when he was a teaching assistant at Sunset Elementary School, “I just wasn’t impressed with the offerings that were out there for kids in science.” In his view, science textbooks all seemed to be either mini-encyclopedias — “a bunch of non-fiction facts” — or were replete with inaccuracies. “So what I wanted to do was address those problems, give to kids real science that was accurate and dealing with ideas, and do it in a way that wouldn’t appeal just to kids who already had that interest. So I needed to have a story to go with it. And that was the hard part because I couldn’t think of a story for about 20 years.”

And then one day he and the real Max, the family’s Rotweiler, were taking Bennett’s son, Grant, who was then about six months old, out walking. “You are supposed to talk to babies and so I was talking and I ran out of things to say,” Bennett recalled. “I looked up in the sky and the moon was up there, and I thought, ‘Hmmm, maybe I will tell him a story about Max going to the moon,’ so I just started making it up as we walked along. By the time we got home, I realized that it was the idea that I had been searching for all those years.”

In the first book in which Max visits the Space Station, the dog comes to the attention of scientists because he has the ability to jump on and off a revolving merry-go-round on the playground, a not inconsiderable talent. His family agrees to let him train to be an astronaut under the watchful eye of Commander Grant, who is named after his son but who is modeled on Lado Jurkin, one of the “Lost Boys of Sudan” who ended up in Colorado. Explained Bennett: “I thought it would be nice to have someone who had come from such difficult real-life circumstances end up in a position of such great responsibility and inspiration to children.”

When Bennett searched for a dramatic situation in which to place the fictional Max on the Space Station, he turned to astronaut Alvin Drew, with whom he became friendly during various collaborations with the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA). Drew told him the most likely problem to occur might be some malfunction in the cooling system. As a result, here is how the story reads after Max becomes acclimated to life on the Space Station:

Max would not stop barking no matter how much Commander Grant tried to calm him. Then Commander Grant noticed that Max was looking intently in one direction.

Commander Grant instantly realized the problem. The Space Station’s cooling system was leaking, which meant that poisonous ammonia gas was getting mixed into the air they breathed. Max and the astronauts would all be killed if they didn’t do something quickly. Fortunately, the crew was well-trained in how to stay calm and focused during emergencies.

Quite coincidentally, astronauts currently aboard the International Space Station have been doing a space walk to fix the cooling system. The cooling problem aboard the Station delayed what for Bennett will be a very special mission, one in which the astronauts plan to read aloud the four books about Max as well as another Bennett creation, The Wizard Who Saved The World. Now scheduled for launch on January 7th, the first commercial resupply mission to the International Space Station by Orbital Sciences, will among its other activities, produce a video of the reading sessions “that will be edited and posted on line for anyone to look at anywhere on the world,” Bennett said.

My 6-year-old grandson Sky, anticipating the interview, wanted me to ask Bennett where Max will travel to next. Bennett responded that he hasn’t decided yet, but that Saturn seems a likely possibility. He noted that the Cassini spacecraft with its Huygens Probe “has been orbiting Saturn since 2004, so in 10 years we have learned an enormous amount about Saturn and its moons.” This gives him, as an author, a tremendous amount of scientific material to work with.

One wonders if perhaps Max should also go to Pluto, especially since that space rock–downgraded by scientists from its former status as a planet–has the same name as one of Walt Disney’s beloved cartoon dogs. Isn’t that the kind of place Max might find interesting?

“I actually want to do Pluto if I continue the series,” Bennett said. “The New Horizons spacecraft was launched in 2006 to go to Pluto and it will arrive in July 2015 and fly by, and so I will need to wait until after that because I will need the scientific information from what we have learned to be incorporated in the story.”

Another grandson, Shor, 12, wondered if Bennett thinks dogs actually will accompany humans on space flights.

The author responded that dogs preceded man into space, with the Russian dog Laika being the first to go into orbit, although it died during the course of the mission. Another Russian space dog, Strelka, returned home safely, and had puppies, one of which, Pushinka, was presented in a bit of Cold War diplomacy by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to U.S. President John F. Kennedy. The puppy was given by the President to his daughter Caroline, who today is the U.S. Ambassador to Japan.

“Certainly you can imagine reasons it might be worth having dogs go… the sniffing capabilities, the companionship on long voyages,” Bennett said. “In reality, you have to balance that…against the costs and the difficulties that would be created.” It might be very difficult, for example, to teach a dog to use a vacuum device for toileting on long space flights. However, he speculated, if ever space colonies should be built, it is likely the settlers would demand that they be permitted to bring their pets.

In Bennett’s stories, all the space crews are international, much like the crew of the original Star Trek television series conceived by Gene Roddenberry, who was an important influence on Bennett.

“Everybody knows how to find the moon in the sky,” Bennett reflected. “You look up at the moon and if you are an Israeli kid or a Palestinian kid, you look up and you say ‘gosh there are scientists from both of our countries working together up there and they are not having any trouble getting along. What is our problem down here?’ I think it could make a real difference in the way people view the world!”

Bennett said he tries to incorporate three important criteria in the stories and textbooks that he writes. These are education, perspective and inspiration.

Education means the facts involved in the science–for example, how weightlessness works or why there is less gravity on the moon. Bennett describes “education” in this context as “the content ideas that we want the students to learn.”

However, “unless you explain to kids why that should matter, why will they bother to learn it? The ‘why bother’ is what I call the perspective, and you will see a lot of that in these books when you look back from the Space Station at Earth, or from the Moon, or Mars. It shifts the way you think about yourself and your planet.”

“Inspiration,” adds Bennett, “is the third piece” when a student resolves “to do the hard work” necessary to learn the material. “Students tend to think everything should come easily and quickly, especially when you look at some of the issues with girls and minorities not doing as well in math and science. What I found a lot of times is that that it gets hard, and when it gets hard, they think, ‘Oh, I must not be any good at it,’ when, in fact, it gets hard for everybody, and if someone just told them, ‘yes, it is supposed to get hard,’ they would realize there is nothing wrong with them.”

We know Bennett’s feelings about dogs going into space, but what about himself? Would he like to travel to somewhere out there?

He responded without hesitation: “I would love to go someday.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com