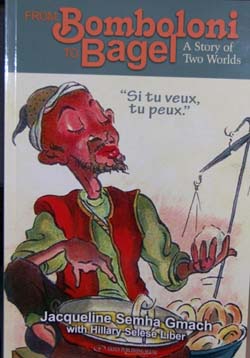

Jacqueline Semha Gmach (with Hillary Selese Liber), From Bomboloni to Bagel: A Story of Two Worlds, Gefen Publishing House © 2014, ISBN 978-965-229-641-2, 288 pages including glossary and epilogue.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –This is a difficult, shockingly honest book, by the woman who helped to engineer, and who perhaps even personifies, San Diego’s emergence as an important arena for Jewish culture through its Jewish book fairs, movie festivals, art exhibits, and stage productions. To one degree or another, and most especially for the book fair, Jackie Gmach nourished and helped develop these events, which many of us Jewish San Diegans now take for granted. Although her hard work resulted in professional success after success and accolade after accolade, we learn that she was so miserably unhappy in her adopted country of the United States that she at least twice was on the brink of suicide.

SAN DIEGO –This is a difficult, shockingly honest book, by the woman who helped to engineer, and who perhaps even personifies, San Diego’s emergence as an important arena for Jewish culture through its Jewish book fairs, movie festivals, art exhibits, and stage productions. To one degree or another, and most especially for the book fair, Jackie Gmach nourished and helped develop these events, which many of us Jewish San Diegans now take for granted. Although her hard work resulted in professional success after success and accolade after accolade, we learn that she was so miserably unhappy in her adopted country of the United States that she at least twice was on the brink of suicide.

From a public relations standpoint, this will not be the easiest book to sell in San Diego, a city for which she often expresses a dislike so intense that a San Diegan, upon reading her sentiments, may be tempted to shout at the pages, “Who’s forcing you to stay, then? Go back to Tunisia or to France or to French Canada, any of those places where apparently you were happier!”

But the San Diego—“the land of the bagel”—that she so vociferously protests against is not really our city of bays, gulls, and canyons, of ocean sunsets, Mexican heritage, pioneer ingenuity, and modern technology. It is rather, for her, a place of unfamiliar language and customs, in which she is separated from generations of her family to whom she still wishes to prove herself, and where, notwithstanding her mantra “si tu veux, tu peux” (If you want, you can), she is beset with frustration.

Her husband, David, decided to take a job here, and—true to her Tunisian upbringing in which major decisions are made by the man of the house—Jackie went with him. To her sorrow, she learned that American families do not have the strong bonds of the Sephardic families of North Africa and Europe. As she separated from her Tunisian parents, so too did her American children move away to form their own lives. Shabbat dinner gatherings still are possible, but more often with friends than with family. Notwithstanding her achievements in education, in teaching, in forging new programs for the community, Jackie is desperately lonely for her parents, siblings, uncles and aunts, and cousins.

There is a sense in this book that Jackie’s move to America interrupted her campaign to prove herself to her parents. Her father, a respected dentist, admired in the mixed Muslim-Jewish society of Tunisia where they lived, was disappointed in her from the day she was born. She was a girl, and he wanted a boy. So Jackie tried to please him by being as close to a boy as she could – a tomboy. This, in turn, disappointed her mother, who wanted her to be a refined young lady. On top of these childhood conflicts was a learning disability that prevented Jackie from reading, at least until a new teacher gently looked into the girl’s eyes, and assured her she would learn to read if she wanted to – si tu veux, tu peux. Not only did Jackie learn to read, she would go on to earn a PhD in the sciences, and through willpower learn to teach those subjects in both French and Hebrew.

Along the way of this book, we share some of Jackie’s adventures and heartbreaks. Her first real love was a French Catholic, and she might have married him, but for her father’s firm no. In the land of Bomboloni (a donut which street vendors fry up while sitting on their haunches), one must receive a father’s blessing. This is not the case in the land of the Bagel. Periodically, Jackie traveled, lived and learned in Israel – and had the pleasure of witnessing Prime Minister David Ben Gurion clearing the dishes from tables in the dining hall of Kibbutz Sde Boker, and on other occasions helping future Prime Minister Golda Meir carry packages to her home from a bus that they both routinely rode.

One wonders why some familiar people mentioned in this book are fully identified with first and last names, while others are referred to only by their first names, and still others are given no names at all. We read of some the details of her romance with David, her special relationship with his mother, but we learn very little about David the husband, or the father. Jackie’s three daughters make only cameo appearances in this narrative. There are other gaps in this book, missing puzzle pieces, if you will. She tells us how she almost jumped off the Coronado Bridge, but omits any reference to her sudden parting with the Lawrence Family JCC, with whose cultural programs she was almost synonymous.

The book is as complex and as layered as Jackie herself is, and her co-author Hillary Selese Liber deserves compliments for an easy-to-read presentation.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com