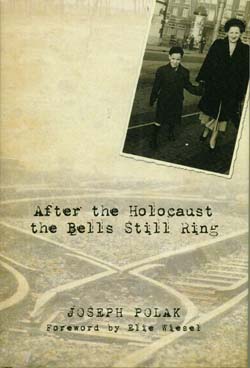

After the Holocaust the Bells Still Ring by Joseph Polak, © 2015 Urim Publications, 141 pages, ISBN 978-965-524-162-4, $19.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—When Rabbi Joseph Polak and his mother were liberated from Bergen-Belsen, he was not yet three years old. He says that he has no actual memory of his early childhood in that concentration camp, nor in the Westerbork camp in the Netherlands where his parents previously had been interned. Yet, he says, the Holocaust lives inside him.

SAN DIEGO—When Rabbi Joseph Polak and his mother were liberated from Bergen-Belsen, he was not yet three years old. He says that he has no actual memory of his early childhood in that concentration camp, nor in the Westerbork camp in the Netherlands where his parents previously had been interned. Yet, he says, the Holocaust lives inside him.

“You never ‘get over it’” he writes in the book’s introduction. “You can lead a reasonably healthy and productive life, while constantly feeling that it can happen again, at any moment. In the early 1950’s, Mother and I never failed to be terrified whenever the doorbell rang unexpectedly.” His Father? He died of disease shortly after liberation and is buried in a mass grave in Troebitz, Germany.

Polak’s memoir, which has drawn an appreciative foreword from Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, is interestingly constructed. As an adult, he retraces his family’s ghastly Holocaust procession, from their home in the Hague; to Westerbork; to Bergen-Belsen; to a “lost transport” that was liberated on the way from Bergen-Belsen to Theresienstadt; to Leipzig, where he was temporarily adopted; to Eindhoven, Netherlands, where he was reunited with his mother; back to the Hague, where he and his mother lived as displaced persons; to a New York-bound ship, to resettlement in Montreal.

It is no ordinary travelogue because Polak sees these places not only with his eyes, nor feels only with his heart, but also summons from deep within his sub-consciousness the emotions, the ironies, the reflections, and the examples, good and bad, of human behavior under extreme stress.

The Nazis came for Polak’s parents before he was born, when for the purpose of keeping their deadly designs secret, the Nazis perpetrated the myth that resettlement simply meant Jews being required to move to another place, where families might work and live together. Thus when Polak’s mother said she was too pregnant to travel, the Nazis were willing to delay the family’s incarceration temporarily. But first Mrs. Polak had to prove to the Nazis that she was indeed pregnant. It was, in Polak’s words, “a double humiliation – Father’s powerlessness, and Mother’s belly-baring.”

In keeping with the policy of hiding their ultimate designs, the Nazis allowed inmates at Westerbork various freedoms. They could have concerts. They even could leave the camp on temporary passes. But every Tuesday, the trains were loaded and quotas had to be filled. A relatively pleasant place, certainly by Holocaust standards, Westerbork was “the mouth that sucked you into the vortex of the Holocaust, from which nearly 100,000 Dutch Jews were deported to Auschwitz, Sobibor, Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt, with no notion of where they were going, except that it wasn’t good,” Polak writes.

In contrast, Bergen-Belsen was a place where “nothing was left to the imagination,” Polak tells us. “Whereas in Westerbork, through bureaucratic paperwork and Monday night lists, we sacrificed the children of friends to save our own, in Bergen-Belsen, at the end, when food had disappeared for weeks, we finally consumed those sacrifices.” Another survivor, seven years older than Polak, never could rid himself of the horror of seeing cannibalism at Bergen-Belsen when “people died while talking to you.”

In Polak’s book, not every survivor was a hero, nor was every Nazi guard a monster. One officer made little Polak his mascot. “Every morning he collected me from Mother’s hut, and brought me to the Appel, from which Mother, because of her advanced arthritis, was exempt. I sat on his shoulder during the counting, she related to me. When he brought me back, Mother said, she would find me counting rhythmically: einz, zwei, drei…”

There are many more insights in this book, which is also laden with a deep knowledge of Judaism. Polak serves as the chief justice at the Rabbinical Court of Massachusetts.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. Your comment may be posted in the box below this article or may be sent directly to the author at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com