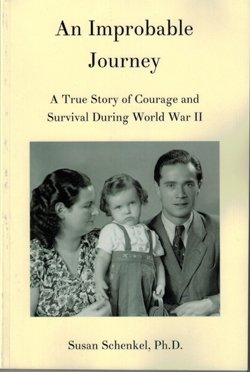

An Improbable Journey: A True Story of Courage and Survival During World War II by Susan Schenkel, Ph.D; ISBN 978-0-9894377-2-1, 183 pages, $12.95

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – After her mother’s death, author Susan Schenkel decided to research the lives that her parents, by then both deceased, had led during World War II and the several years between its end and the family’s new beginning in the United States.

SAN DIEGO – After her mother’s death, author Susan Schenkel decided to research the lives that her parents, by then both deceased, had led during World War II and the several years between its end and the family’s new beginning in the United States.

No doubt Schenkel would agree that had she commenced this task while her mother was alive, information for this biography would have been so much easier to come by. Nevertheless, over the years, her parents and relatives had shared sufficient information with her to point Schenkel in the right research direction.

Schenkel’s mother was born Siddi Fedelheim in 1918 in Berlin to a Lithuanian Jewish father and a German Jewish mother. They died while Siddi was still of elementary school age, but there were many relatives and older siblings to keep the family together enjoying German culture during the days of the Weimar Republic.

After Hitler came to power, however, the Nazis ruled that because the Fedelheims’ father had come from Lithuania, his children were aliens, ineligible for the rights and services extended to other Germans. This was good news in disguise, as it prompted the family to scatter to other countries before Hitler had a chance to enact the draconian laws prohibiting Jews of any nationality from numerous activities and still later leading to the forced labor and murders of the Holocaust.

Siddi followed a brother to Kovno, Lithuania – a first step in an odyssey that would later see her flee, ahead of the Nazis, from Lithuania to Russia from whence she was deported to Samarkand in Uzbekistan. Married by a rabbi to an idealist, Pifcus Dembowski in Lithuania, Siddi many years later told her daughter that she was given a divorce decree by another rabbi in Uzbekistan. It was in Samarkand that Siddi met Leon Schenkel, who would many years later record details of his life for the Kupferberg Holocaust Resource Center at Queensborough Community College in New York City.

Nine years older than Siddi, he had been born in Tarnow, Poland, the son of a Hebrew school teacher in a Hassidic community. At age 16, he left home to live in Bielsko with the privileged, assimilated family of his aunt, Mrs. Adolph Danziger. Under their tutelage, he became a successful salesperson for a company that sold elastic. His cultured lifestyle was similar to what the Fedelheim family had once experienced in Berlin. If it was not a total repudiation of Orthodox Judaism, it was a rejection of his abusive father and the lifestyle that had kept his family mired in poverty.

After Hitler and Stalin partitioned Poland, Leon made his way to Lvov in the Russian sector, from whence he was deported by Soviet authorities to a labor camp in Gorki. He was released from the labor camp after the Germans invaded the Soviet Union. He made his way to Tashkent, the largest city of Uzbekistan, located about 175 miles from Samarkand. He purchased bread in Tashkent and sold it in Samarkand, then purchased tobacco in Samarkand and sold it in Tashkent. Such enterprise was illegal under the controlled Soviet economy, but such black market dealings kept him alive.

Leon spotted Siddi at a café, and brazenly sat down at her table. “Don’t eat by yourself,” he told her. “Eating alone makes one fat. Share your berries with me.” What he lacked in polish, he made up in rugged good looks and the projection of strength. In addition, wrote Schenkel, “He was persistent. He courted her. It was a courtship, wartime style. Instead of flowers, Leon brought Siddi food. Sometimes he stole food for her…”

Before the advent of the Nazis, both Leon and Siddi had partaken of the finer things in life—art, culture, good conversation, gourmet food. Now, in a country where Muslim customs were in marked contrast to those of Christian, pre-war Germany, the young Jewish couple had to scratch for a living, They often suffered hunger, and made do without many of the amenities which they once had taken for granted.

After marrying, the couple eked out a living in Samarkand, where Siddi became pregnant with the author, her first and only child. When the tides of war reversed, Leon and Siddi worked their way behind advancing Soviet troops back to Poland, later crossing into southern Germany, to a displaced persons camp in the city of Ulm. There, Susi spent the first several years of her life, often in the company of a kindly Christian German family, whom her parents warmly befriended notwithstanding what Germany had done to Jews. Eventually the Schenkels immigrated to the Forest Hills section of New York with the help of relatives who had preceded them.

The hardships the couple overcame in their “improbable journey” helped to shape their personalities. Siddi, it seemed, thereafter was always trying to recapture the fun, culture and gentility of her youth. She was notably standoffish in the company of less worldly neighbors. Her relatives, who had arrived in America well before her, were even more snobbish, at one point suggesting to Siddi that she divorce Leon, whom they considered to be beneath her. Leon overheard and gave them a piece of his mind, and thereafter the relationship between the two branches of the family remained tense.

I found myself wondering as I read the book, and followed the couple’s travels, how much a biographer can really learn about someone who has already died, even if it is a relative. Yes, we can follow a person’s physical movements, understand the forces like war and depression that drove their actions, report upon the documents and verbal interviews the person left behind, and incorporate into our narrative commentaries by contemporaries about that person. But such information can take us only so far. It doesn’t allow us, so to speak, to get behind that person’s eyeballs, to see what they see, nor into their brains to process information as they did.

As I noted at the outset, the biography would have been so much easier for Schenkel to write if her mother was still alive. So, one takeaway from the book, besides that her parents led interesting lives, is that if you want to understand someone still living, there is no time like the present to capture as much information as you possibly can, be it in correspondence, audio tape or videotape.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. Your comment may be sent to donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com, or posted on this website, per the instructions below.

__________________________________________________________________

Care to comment? San Diego Jewish World is intended as a forum for the entire Jewish community, whatever your political leanings. Letters may be posted below provided they are responsive to the article that prompted them, and civil in their tone. Ad hominem attacks against any religion, country, gender, race, sexual orientation, or physical disability will not be considered for publication. Letters must be signed with your first and last name, and you must state your city and state of residence. There is a limit of one letter per writer on any given day.

__________________________________________________________________