By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Like many Israelis, Asaf Hanuka and Boaz Lavie served in the IDF, meeting each other on the staff of an Army newspaper. Hanuka had learned to draw by copying comic books sent to him by relatives in Santa Monica, California. Lavie had studied screen writing at a special high school for the arts in the Tel Aviv area. Together, they not only covered and illustrated the news but invented a comic strip about an Israeli soldier lost in Lebanon.

SAN DIEGO – Like many Israelis, Asaf Hanuka and Boaz Lavie served in the IDF, meeting each other on the staff of an Army newspaper. Hanuka had learned to draw by copying comic books sent to him by relatives in Santa Monica, California. Lavie had studied screen writing at a special high school for the arts in the Tel Aviv area. Together, they not only covered and illustrated the news but invented a comic strip about an Israeli soldier lost in Lebanon.

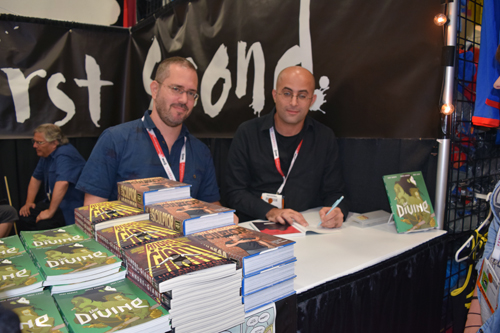

Hanuka said although the strip raised troubling questions about the welfare of soldiers, they were not taken as anything more than entertainment because the medium for the message was a comic strip. Here, at San Diego’s annual Comic-Con Convention, which may be attended by as many as 130,000 persons through Sunday July 12, the power of comics is understood and revered. And here Lavie and Hanuka will be debuting to the American audience The Divine, a graphic novel on which they and Hanuka’s brother, Tomer, collaborated for over five years.

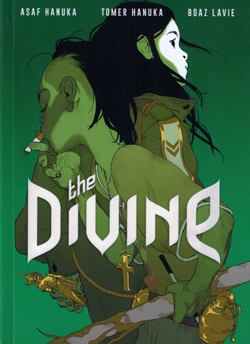

The story, mixing realism, gore, and fantasy, was inspired by a photograph taken in 2000 by Associated Press photographer Apichart Weerawong of war-weary 12-year-old Burmese twins Johnny and Luther Htoo, who headed what other children called “God’s Army, a resistance movement of youngsters-turned-guerrillas fighting against the take over of their family lands. Asaf’s brother Tomer was moved by the photograph, and eventually he and Hanuka did some concept drawings. The project jelled after they recruited Lavie to write it.

Lavie utilized the concept of children-soldiers to create a story about an American military veteran with mounting debts and a pregnant wife being lured by a mercenary to make some quick money by participating in a military action in a far-off Asian country.

After the American arrives, he is lured by an injured child back to the camp of the “enemy” whom he learns are also children. The idea of fighting children sickens him, but his mercenary pals are relentless. Eventually, invoking “divine” powers, perhaps better described as supernatural powers, the children defeat the mercenaries while sparing the American recruit.

In over 150 pages of illustrations, and text, the Hanuka brothers and Lavie reflect on questions that trouble soldiers the world over.

“There is the issue of the mercenaries who go there – that is a question about global politics; the way that people are unaware of the meaning of their actions, and very easily go places, take part in so-called adventures without giving thought to the implications of their actions,” Lavie said during an interview at the beginning of the Comic-Con convention.

“In this story we try to shed some light on the possibility of being involved, as a regular person living a very simple life, in such a difficult, horrific situation. That is a situation where your moral decisions, your consciousness starts working at a high level. Daily decisions have a very deep meaning, because you deal with the lives of people.”

It is not only the mercenaries who can wreak damage, Lavie pointed out, it is also the people at home who passively support such operations, knowing very little about the people who are being described as an enemy.

Hanuka said that as an artist he had a visual perspective on the story: “It was interesting to find the contrast and the distance between the western world, which is the first third of the book, and happens in Texas somewhere, and the rest of the book which happens in this imaginary jungle of Quanlom and so there is the question of the color palette and the fact that the western world is built with straight lines in an environment that is urban, and the jungle which is Asian is much more abstract. And I think that is something that reflects, in the story, that usually western society has a set of rules, and really believes in these rules like a religion: ‘this is how this world works, there is profit, there is gain, everything has a price, this is what you need to do to be a good man or to make money.’

“You confront this set of beliefs in a different society that believes in something very different that for a westerner might look like an imaginary story or a kid story, or fantasy,” Hanuka continued. “Sometimes you must respect this difference if you are to avoid destroying it.”

I could not resist asking why they set their story in a fictional east Asian country rather than in Israel or other parts of the Middle East. They responded that while some of the themes are universal, Israeli society is so polarized that the book might be interpreted as being “for” or “against” one side or the other and wind up being controversial from the get-go.

“I think in Israel today, after last summer (the Gaza war), it is very easy for people to judge you if you are going to tell a story that touches the conflict,” responded Hanuka. “They are going to say that you are taking sides, so it is either that you are with them or against them. The judgment will come before the story. The only way to talk about the conflict is to put it somewhere else.”

At this Comic-Con, where many fans wear the costumes of their comic book heroes – and those who don’t. happily photograph those who do—Stan Lee, an icon of the industry who created many of the world’s well-known super heroes is among the “big names” appearing on panels.

Lavie and Hanuka expressed surprise when I told them that Lee at past Comic-Cons proved himself an easygoing fellow who is quite approachable. They imagined because he sits at the apex of the world of super-hero creators, he might be far more remote.

Hanuka said that Lee’s fame and creations are known so globally that they prompted two twin brothers in Tel Aviv to start drawing and to dream of one day of creating their own heroes. Lavie said nothing would give him greater pleasure than to meet Lee and to present him with a copy of The Divine.

At a magical place like Comic-Con, this is no fantasy.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. You may comment to him at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com, or post your comment on this website provided the comment is civil and that you identify yourself by full name and your city and state of residence.