–16th in a series–

Exit 6, Qualcomm Way, San Diego ~ Qualcomm Stadium,

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — In 1997, Qualcomm, a telecommunications industry giant co-founded by Jewish electrical engineers Irwin Jacobs, Andrew Viterbi and others, paid the City of San Diego $18 million for San Diego Jack Murphy Stadium to be renamed for 20 years as Qualcomm Stadium and for Stadium Way, which runs from Interstate 8 north to Friars Road, to be renamed as Qualcomm Way.

By taking Qualcomm Way to Friars Road and turning right, travelers can within a short distance access the parking lot of the stadium where the San Diego Chargers play in the National Football League and the San Diego Aztecs play college football. The stadium once housed the San Diego Padres of baseball’s National League, but that team moved to its own stadium in Petco Park in downtown San Diego in 2004. In 2015, the Chargers were entertaining offers to play at a new stadium in Los Angeles County.

Qualcomm, an abbreviation for “Quality Communications,” was created in 1985 after Jacobs and Viterbi left Linkabit, a company they previously had founded, to serve as consultants in the telecommunications industry.

During their reign, Linkabit consulted to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on methods of sending data and photographs from space probes; with the U.S. military to relay information to aircraft anywhere in the world; and with such commercial entities as Holiday Inns, 7-11, and Walmart to enable their headquarters to transmit videos to their companies across the nation. They sold the company in 1979 to M/A-Com, and decided to leave in 1985 to form another communications company.

Initially, Qualcomm sold Omnitracs software to trucking companies to enable them to stay in touch with their fleets, wherever in the country their trucks might travel. They also acquired Eudora, a company whose email program was compatible with Omnitracs. For a while, Qualcomm also manufactured cellphones, but sold that business to Kyocera. The reason: Far more profit could be made in developing communications software that could be sold to multiple cellphone manufacturers. In this Qualcomm had a distinct advantage, in that Viterbi had patented the Viterbi algorithm for separating telecommunication signals from noise in the atmosphere. Building on this knowledge, Qualcomm developed code division multiple access (CDMA), a proprietary technology for use in cellular communications.

The company thereafter grew by leaps and bounds, becoming one of San Diego County’s largest employers.

The street name “Qualcomm Way” corresponds to the ethics statement of Qualcomm employees, which they call “The Qualcomm Way.” In it the employees makes four pledges. 1) “We act with integrity in everything we do.” 2) “We lead by example with transparency, and by encouraging each other to raise concerns and ask questions.” 3) “We trust each other and are responsible and accountable for our actions, while interacting in a collaborative, respectful and professional manner.” 4) “We have a collective drive for success and are constantly thinking of new and innovative ways to do things.”

*

(Following adapted from Schlepping Through the American West: There Is a Jewish Story Eveywhere by author Donald H. Harrison.)

Qualcomm Stadium, as it is called in its third incarnation since opening in 1967, is a massive concrete structure described as “modernist” by some architects, “brutalist” by others. Either way it is a celebration of structural forms and building materials. Its massive slabs of unadorned concrete give the impression of overwhelming power, not unlike that of a 320-pound tackle advancing on a 180-pound quarterback. Modernism is an architectural style that was made popular in San Diego four years earlier when polio vaccine discoverer Dr. Jonas Salk and architect Lous I. Kahn, two admired Jewish leaders in their fields, unveiled in La Jolla the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, an eye-arresting complex of buildings starkly beautiful and overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

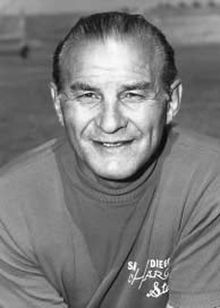

(Photo: Wikipedia)

When the stadium opened for business, it was called simply San Diego Stadium. On Sept. 9, 1967, the San Diego Chargers, then of the American Football League, played the first official game of the season here. They had a Jewish coach by the name of Sid Gillman, who previously had led them through their paces at the now demolished Balboa Stadium. In 1963, under his guidance, the Chargers won the league championship with a commanding 51-10 defeat of the Boston Patriots. Perhaps because of all the excitement engendered by a new stadium, it looked like the Chargers would dominate the league again in 1967. In their first ten games, they ran up a record of 8-1-1, but then disaster, in the form of the Oakland Raiders, struck. Having handed the Chargers their only loss earlier in the season, the Raiders did it again 42-21. The dispirited Chargers then lost the next three games to end up in third place with an 8-5-1 record. When Gillman and his all-American lineman Ron Mix, also Jewish, looked at each other, there was really only one thing to say: “Gevalt!”

If Gillman had something to cheer about, it was that NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle took him up on his idea of having a game played between the champions of the National Football League and the American Football League. Today the Super Bowl is an American institution.

Another Jewish sportsman, Gene Klein, had purchased the Chargers in 1966 and held onto the team until 1984. He also owned the Seattle Supersonics of the National Basketball Association and raced thoroughbred horses. A friend and fan, Lou Harris, recalls that when Klein was asked to compare football and horse racing, he responded that when his horses win, they never ask for an increase in salary.

In 1968, the Chargers got some professional sports company at the stadium. A new tenant was the minor league Pacific Coast League team known as the San Diego Padres. In 1969, the Padres were accepted as an expansion team in the major leagues and were assigned to the National League.

In the first game of its major League season, the Padres won 2-1 against the Houston Astros, but after that things just got worse and worse. The Padres wound up their season dead last with a record of 52-110.

Although there have been distinguished moments in the history of the two professional franchises, the sad fact of the matter is that since the Chargers’ establishment, the team has thus far played in only one Super Bowl. The Padres have a slightly better record, having fought their way to two World Series. However, the two San Diego teams lost all three of these championship contests.

In 1980 San Diego Union sportswriter Jack Murphy died, and in appreciation for the key role he had played in getting professional teams to move to San Diego, and persuading voters to approve the bond issue to build the 50,000-seat stadium (it has since been expanded to over 70,000 seats), the stadium was renamed in his honor as San Diego Jack Murphy Stadium, or “the Murph” for short.

Later on, in 1997, naming rights for the stadium were sold for $18 million to Qualcomm, but Murphy is still remembered because Qualcomm Stadium surrounds what is called Jack Murphy Field.

There is a statue of Murphy and his black Labrador hunting dog, Abe of Spoon River, standing between one of the entrances of the stadium and the platform of the San Diego Trolley Station serving Qualcomm. True, Murphy was Irish but in his Labrador, there was a Jewish story. Abe was short for Abraham. One of the puppies that dog sired was named Isaac. Alas, he wouldn’t hunt, so Murphy gave him away. The name of his third dog? You guessed it, Jacob.

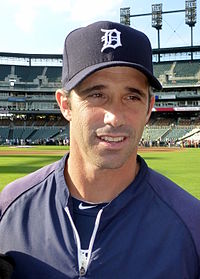

(Former Padre)

As the Chargers early in their franchise had a Jewish player in Ron Mix, so too did the Padres have theirs in Brad Ausmus, who made his major league debut as a catcher in the 1993 season and stayed with the team until 1996 until he was traded to the Detroit Tigers, the team for which he became the manager in 2013.

Gillman, Mix and Ausmus all have been inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in Suffolk County, New York.

Not all the Jewish stars who performed at Qualcomm Stadium are so kindly remembered. In 1990, Roseanne Barr decided to make a comedy act out of singing the National Anthem before a Padres game against the Cincinnati Reds. She screeched out the words, and then in imitation of a baseball player, scratched her crotch and spat. The crowd didn’t care for the satire and the booing, in the form of controversy, continued for many weeks thereafter.

Although the Chargers got to play in only one Super Bowl, the stadium has hosted three such contests featuring other teams. In 1988 the Washington Redskins defeated the Denver Broncos 42-10. Ten years later, in 1988, the Denver Broncos defeated the Green Bay Packers 31-24. And in 2003 Tampa Bay beat the Oakland Raiders 48-021. Many Jewish San Diegans have been privileged to attend all three games, among them Charles Wax, chairman and chief executive officer of Waxie Sanitary Supply.

There also have been two All-Star Games played here. The National League won 7-3 in 1978, in a game in which a fellow who was often thought to be a Jew–but wasn’t–played. That was Rod Carew, then a first baseman for the Minnesota Twins. When Saturday night Live’s Adam Sandler wrote his Chanukah song, one of the lyrics said that “Rod Carew is a Jew—converted”–but in fact he wasn’t and hadn’t. His wife was Jewish and their child was being raised Jewish, but Carew himself remained Christian. The other All-Star Game at “The Murph,” in 1992, saw the American League prevailing, 13-6. Another All-Star game will be played in 2016 in San Diego, but it will be at Petco Park, the Padres new home.

Jews have moved in and out of the Padres front office as a succession of management teams came and went, but one well-known Jew who has been more or less a fixture for the Padres has been radio announcer Ted Leitner, who used to be the TV sportscaster on KFMB-TV, Channel 8. Leitner has the knack of giving running play-by-play descriptions while filling in those moments between the action with anecdotes about almost every professional player in every sport ever played in San Diego.

The Padres moved from Qualcomm Stadium in 2004 to Petco Park in downtown San Diego, and the San Diego Chargers have been campaigning for a new stadium as well, sometimes broadly hinting if one is not forthcoming the franchise will be moved to another city. Meanwhile, Qualcomm Stadium remains the home field for the San Diego Aztecs as well as the host to two College Bowl games played in the winter–the Holiday Bowl and the Poinsettia Bowl — each of which has enthusiastic fans. It also has been the venue for numerous concerts, religious revivals, games of the short lived San Diego Soccers team, and has served as an evacuation center when major wildfires forced thousands of San Diegans to flee their homes.

A point of personal pride: When the late Tony Gwynn retired at the end of 2002 from baseball after playing all 20 seasons of his major league career for the Padres, there was a ceremony at Qualcomm Stadium that involved various VIPs followed by Tony and Alicia Gwynn walking through a 9-foot diameter baseball that had been crafted from balloons. The Jewish angle was that my daughter, Sandi Masori, and her husband, Shahar, owners of Balloon Utopia, made that giant baseball portal!

Next: Team Davis and the Tikkun Olam imperative

**

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. You may comment to donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com or post your comment on this website provided that the rules below are observed.

__________________________________________________________________

Care to comment? We require the following information on any letter for publication: 1) Your full name 2) Your city and state (or country) of residence. Letters lacking such information will be automatically deleted. San Diego Jewish World is intended as a forum for the entire Jewish community, whatever your political leanings. Letters may be posted below provided they are responsive to the article that prompted them, and civil in their tone. Ad hominem attacks against any religion, country, gender, race, sexual orientation, or physical disability will not be considered for publication. There is a limit of one letter per writer on any given day.

__________________________________________________________________