-21st in a series-

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Two of my grandsons were born at the Kaiser Permanente Hospital that towers over the intersection of Mission Gorge Road and Zion Avenue. Given that the hospital’s address is 4647 Zion Avenue, I sometimes joke that these descendants were natural born “Zionists.”

SAN DIEGO – Two of my grandsons were born at the Kaiser Permanente Hospital that towers over the intersection of Mission Gorge Road and Zion Avenue. Given that the hospital’s address is 4647 Zion Avenue, I sometimes joke that these descendants were natural born “Zionists.”

But no such flights of fancy are needed to tell the “Jewish story” of this hospital. Because this hospital, as well as all the Kaiser-Permanente facilities, were an outgrowth of the innovative spirit and farsightedness of a young Jewish physician from Los Angeles—Dr. Sidney Garfield—who in 1933 established a 12-bed hospital in Desert Center, in the far reaches of the Mojave Desert, to tend to the health of 5,000 Metropolitan Water District workers who were building an aqueduct to bring water to Los Angeles from the Colorado River.

Dr. Paul Bernstein, San Diego medical regional director for Kaiser Permanente, is quite knowledgeable about Garfield, having told his story in the novel Courage to Heal. While some of the conversations and the love story in that book were products of Bernstein’s fertile imagination, he said he hewed strictly to the facts in describing Garfield’s progress as a doctor and Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) administrator.

Bernstein told me that as a boy Garfield wanted to be an architect. But his mother thought him becoming a doctor was more fitting. He trained as a surgeon at Los Angeles County Hospital, which today is known as USC Medical Center, “where they were bringing injured workers from the aqueduct on a six-hour ride to treat them for trauma, and a lot of them died on the way,” Bernstein said. Workers called the ambulance “the oven on wheels.”

So Garfield went out to Desert Center because “it was the Depression and there weren’t a lot of other jobs, and second because there were thousands of workers who needed health care. With a $2,500 loan from his father and by getting a lot of incentives from some companies — surgical companies, air conditioning companies, General Electric — he was was able to create a small hospital in the desert. By the way, this was the first hospital in America to have air conditioning where the patients were and not where the doctors were. It was unique, caring about how the patients were feeling.”

For the next part of the story, Bernstein depended on “Kaiser lore” rather than on documented facts. According to the oft told story, industrialist Henry Kaiser, who had been a prime contractor on the Boulder Dam (now called the Hoover Dam), literally jumped off a train near Desert Center to get in a successful bid for the Six Companies consortium to build the Parker Dam. He suffered minor injuries and, accompanied by his insurance executive Harold Hatch, encountered Garfield at the desert hospital.

Kaiser and Hatch learned that rather than wait for patients to be hospitalized, Garfield was an advocate of pre-payment for health care. Workers were asked to contribute 5 cents per day to insure themselves against huge medical bills in the event of an accident. Well over 90 percent of the workers did so, enabling Garfield to further capitalize his small hospital.

For an additional nickel a day, workers were able to pre-pay the costs for treatment for non-work-related illnesses that might befall them. This plan also proved to be a success, not only financially, but more importantly, in how it gradually changed the outlook of the hospital world. With income already assured via prepayment, hospital personnel needn’t hope that enough sick patients would be wheeled through the doors to defray expenses and salaries, nor were they tempted to order unnecessary tests just to jack up the fees. Instead the doctors and nurses could emphasize preventative medicine, helping enrollees to stay healthy, and –as is said in KP’s advertising slogan voiced in TV commercials by actress Allison Janney (The West Wing, Mom) —to “thrive.”

After the aqueduct construction was completed, Garfield was invited by Kaiser to set up a similar plan at the construction site of the Grand Coulee Dam, enrolling 6,500 workers and family members. Not long after the dam was completed, the Japanese attacked the U.S. Naval Fleet at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii, precipitating American entry into World War II. There was tremendous urgency to rebuild America’s naval fleet and to win back control of the Pacific Ocean from the Japanese. Some 30,000 workers were hired by Henry J. Kaiser, under a U.S. military contract, to build ships at six facilities in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Once again Kaiser wanted Garfield on his team. Together they set up first aid stations at the shipyards, as well as a field hospital in Richmond, and a major hospital in Oakland for the most serious cases. This was the beginning of Kaiser-Permanente, into which members of the public were permitted to enroll as World War II wound down. The era of the health maintenance organization (HMO) had begun, and Kaiser-Permanente Hospitals branched out from the San Francisco Bay Area to other parts of the nation, including San Diego.

In the Summer 2006 issue of Permanente Journal, a peer-reviewed quarterly journal of medicine, doctors pondered the contributions to the medical profession made by Garfield, who since and before his death in 1984 had attained legendary status.

Dr. Jay Crosson recalled that Garfield “was a fount of ideas—virtual intellectual fireworks—admittedly igniting a few duds among the brilliant rockets. The ideas ranged across the entire spectrum of health care, from delivery models to financing to hospital design.”

He suggested that four ideas, in particular, resulted in innovations for which Garfield will be remembered. In addition to pre-payment, these included: group practices with multiple medical specialties; an emphasis on keeping people healthy; and utilization of technology for accurate medical record keeping.

Crosson quoted Garfield as saying “The computer cannot replace the physician, but it can keep essential data moving smoothly from laboratory to nurse’s station, from x-ray department to the patient’s chart and from all areas of the medical center to the physician himself.”

In a personal remembrance, Dr. Robert Feldman wrote:

Over the 15 years of our collaboration, I spent a great deal of time with Dr. Garfield working on research regarding health care delivery. I saw him almost daily under many different circumstances. He was a remarkable man – patient, tolerant, always considerate, soft-spoken, almost shy, but strong – a complete gentleman. He treated construction workers as he would important administrators or physicians. He was generous and unpretentious. I never heard him gossip or criticize his medical colleagues. He said he sought out and tried to employ the strengths of the people he worked with. He readily acknowledged a good job, and if he didn’t have anything positive to say he didn’t say anything. He was dapper and dressed well in custom-made clothes. He didn’t carry a wallet, just a credit card and a few large bills—he had class.”

Bernstein never met Garfield personally but he was a resident at the Zion Avenue Kaiser Hospital in 1978, the same year that Garfield popped into the Emergency Room at 2 a.m., identified himself, and asked to be shown around so he could see “how things work in San Diego.” Dr. Jeffrey Selevan, a fellow Jew, was serving as chief of the emergency room at the time, and he showed him around. “He was obviously excited to meet him,” said Bernstein. Seleven incidentally went on to become the chief financial officer for the Kaiser Medical Group for a number of years.

After World War II, Kaiser-Permanente became more and more successful as a result of labor unions and businesses enrolling their members in the pre-payment plan. While Kaiser and Garfield agreed on many things, “like brothers, they had their differences too, which resulted in 1955 in our famous civil war between Sidney Garfield and Henry Kaiser, that was between the medical group and the business arm, which we call the ‘health plan.’ They had a disagreement that almost disintegrated the Kaiser-Permanente plan back in the 1950s,” Bernstein related. “Henry Kaiser felt strongly that he could do a better job of controlling outcomes and costs than physicians could, so he started to want to control it just like his businesses of steel, aluminum, shipbuilding and cars, to name a few, because he was very controlling. He wanted to make medical decisions and the doctors pushed back. The doctors believed they should make all decisions about patient care, whereas Kaiser felt that businessmen could make those decisions as well, and more cost effectively than the doctors.”

“They came to impasse,” Bernstein continued. “Henry Kaiser said ‘great I will sell you the whole program. Give me $3 million and I will give you the hospital and everything.’ Doctors at that time were making $600 per month, so they couldn’t afford anything near that. The doctors, Henry Kaiser and his business group got together at Henry Kaiser’s famous mansion at Lake Tahoe, called Fleur du Lac (Flower of the Lake) where years later they filmed a segment of The Godfather movie — the part where the Godfather’s brother is taken out to the lake and is done away with. That meeting in 1955 resulted in our current medical services agreement on structure…. The doctors make all the medical decisions, and they work with the health plan to make business decisions, a fully integrated system of care. Sidney Garfield had been head of the medical group at the time, but he stepped down as part of the agreement and went over to work with Kaiser on the health plan side.”

The basic agreement, still in effect today, has generated the Kaiser concept of “the right care based on medical guidelines and outcomes and what is going to help that patient get well, and not just order tests randomly to generate fees,” Bernstein said. “It’s health care based on wellness and prevention and not the traditional sick care based on treating patients only when they are ill. We want to do everything we can to keep the patient healthy, so that if you look at our testing rates for colonoscopies and mammograms, we lead the nation in preventive care, and this is in contrast to ordering inappropriate tests, such as MRI’s, for anyone with a headache, where it is not always indicated.” Such decisions, he said, are based on national studies and guidelines.

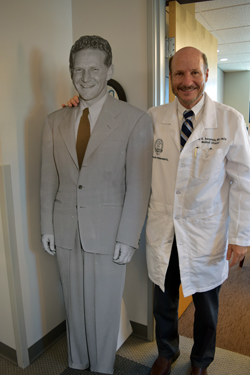

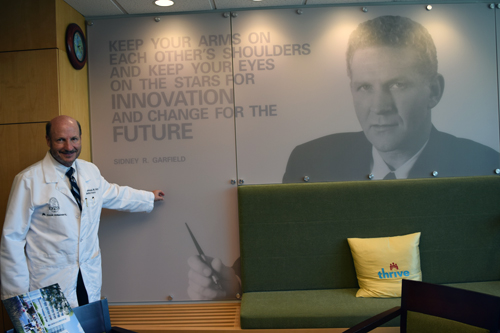

In Bernstein’s office is a large photographic mural of Sidney Garfield, together with his saying: “Keep you arms on each other’s shoulders and keep your eyes on the stars for innovation and change for the future.” Outside Bernstein’s office is a full size stand-up poster of Garfield, his hero.

“Almost everything we do in American medicine today was really developed by him,” Bernstein said admiringly. “Think about it, prevention and wellness, he came up with in the 1930’s. Focusing on a patient from everything from air conditioning in the patients’ rooms to providing care that keeps them healthy, to getting them in sooner for care rather than later. … back then our morbidity and mortality from pneumonia were significantly less than any hospital in California because patients came in before their colds and upper respiratory infections turned into pneumonia. At the same time patients with appendicitis did well because they came in before their appendix ruptured because they didn’t have that barrier in terms of fees. They came in sooner so we had the best care and outcomes. The same thing applies today in terms of prevention.”

A new Kaiser Central Hospital near the intersection of Interstate 15 and Clairemont Mesa Drive is scheduled to open in 2017, at which point some of the specialties will be housed there and others will continue to be housed at the Zion facility, according to Bernstein. “Our Central Hospital in Kearny Mesa will be more advanced and innovative than any hospital in San Diego. It will include a neurosurgery center of excellence, cardiac center of excellence, and, a maternal and child center of excellence. Zion will become a center for orthopedics, hematology and oncology, and other centers still under development. We will have emergency rooms at both.”

*

Next: A world champion’s tennis club

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. You may comment to him at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com, or post your comment on this website provided that the rules below are observed.

__________________________________________________________________

Care to comment? We require the following information on any letter for publication: 1) Your full name 2) Your city and state (or country) of residence. Letters lacking such information will be automatically deleted. San Diego Jewish World is intended as a forum for the entire Jewish community, whatever your political leanings. Letters may be posted below provided they are responsive to the article that prompted them, and civil in their tone. Ad hominem attacks against any religion, country, gender, race, sexual orientation, or physical disability will not be considered for publication. There is a limit of one letter per writer on any given day.

__________________________________________________________________

Pingback: Kaiser Children Health Insurance | INSURANCES

Pingback: Alameda County Water District Insurance | INSURANCE

Pingback: American College Physicians Disability Insurance | INSURANCE

Very Interesting! — Mimi Pollack, La Mesa, California