By Donald H. Harrison

SAN FRANCISCO — When I visit science museums, I have come to expect to see interesting optical illusions such as a picture that looks like Marilyn Monroe when viewed from one vantage point, but becomes Albert Einstein when seen from another perspective.

I enjoy watching educational games such as the one my granddaughter Sara played in which she had to keep track of three moving blue balls on a screen as they gradually turned to the same green color as the other balls on the screen. She had to remember which balls had started off blue. The game illustrates the difficulties encountered when you divide your attention. It’s a good lesson for anyone who thinks they can drive a car and text at the same time!

There are more than 600 interactive exhibits, including some in the social sciences, at the Exploratorium, which is located at Pier 15. My wife Nancy and I found the social science exhibits so fascinating that we devoted much time during our recent visit to them.

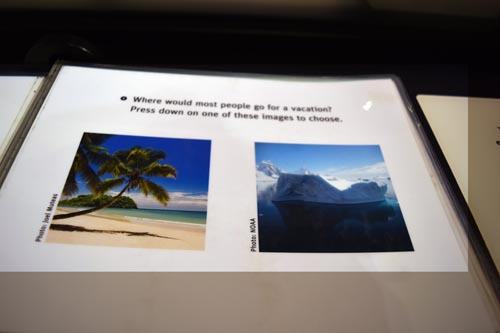

One of the experiments reminded us of the daytime television show, Family Feud, in which contestants have to predict how most people would answer simple questions. In our case, we were shown two photographs, one of a tropical island, the other of icebergs and glaciers. Sitting across from each other, but looking at the same set of photographs, Nancy and I each pressed our thumb on the photo of the place we thought most vacationers would want to go.

I pressed the picture of the tropical island; she pressed the icebergs and glaciers. The computer indicated that Nancy was right and I was wrong, so what else is new? She is a travel agent who specializes in cruise ship vacations and she knows how popular cruises to Alaska and to the Scandinavian fjords are. It turns out more people would like to go there on vacation than to go to a sun-soaked tropical beach.

At another exhibit, we each looked through a deck of cards bearing different pictures and were asked to pick four cards that we thought best illustrated an important concept — like trust or collaboration.

The photos we independently chose included a couple getting married, a child looking at her pregnant mother’s stomach, a toddler, and a mother pig nursing her young. Married nearly 48 years, Nancy and I do have some ideas in common!

Next, we were posed with what was described as the diner’s dilemma:

You and a group of friends meet for dinner. You agree whatever the final cost, you will split the bill equally. Now the dilemma: How expensive a meal do you order? You might reason that you should eat extravagantly because the extra cost of your expensive dish will be shared and result in only a small increase in the total bill. However, if everyone reasons this way and orders an expensive dish, the bill will be high enough to offset your enjoyment of the meal.

So what do Nancy and I do? Neither of us order extravagantly, typically preferring to stay in the low to medium price range on the menu. When we go out with other couples, we sometimes split the check and other times arrange for two separate checks, depending on what seems more comfortable. If, when splitting the check, the other couple orders well above our normal price range, we pay our half of the bill without objection, but quietly resolve that on the next occasion that we all go out, we will arrange for separate checks.

At yet another exhibit station, we were asked to consider some life or death moral dilemmas.

Scientists and philosophers often pose difficult social questions to learn how we make moral judgments. The Trolley Car Problem asks you to imagine five people on a track as a train approaches. The only way to save them is to pull a lever to divert the train to another track — but if you do, it will hit and kill another person. What do you do?

Many say they would divert the train, reasoning that saving five by killing one is morally sound. But when the problem is changed to say that the only way to divert the train is to push a person onto the tracks, responses change. Even though the outcome is identical — one person is killed to save five — the action of pushing a person onto the tracks feels less morally acceptable than pulling a lever to accomplish the same goal.

I found myself agreeing with this analysis, but Nancy demurred. “You could jump onto the tracks yourself,” she said. She always has been self-sacrificing, and if the people needing to be saved were friends or relatives I perhaps could see her point, but for strangers? Honestly? I don’t know that I could do that. Could you?

Another quandary asks you to imagine coming upon a drowning child. You can jump in to rescue him, but that would ruin your $500 suit. People commonly say that they would certainly save the child, that it would be wrong to ignore the situation. But research suggests that very few people donate such a sum to organizations that save lives through the provision of food, water or medical treatment.

Why do we behave so differently in logically similar situations? One answer is vividness: We act differently when decisions are described in statistical terms or require impersonal actions than when we can see the effects of our actions on real people. Another is framing: We are more likely to take risks when decisions are presented in terms of losses (for example, lives or money lost) than in terms of gains (lives or money saved.)

I accepted this analysis, but Nancy felt it didn’t go far enough. We can understand the direct action of saving a drowning child, but with charities one’s contribution may go through so many levels of administration, it may end up doing no good at all, she said. We’ve all heard the horror stories of charities supposedly devoted to worthy causes that forward only a tiny percentage of their receipts for the cause, keeping the rest for themselves.

We believe, therefore that it’s best to utilize “Charity Navigator” to determine how effective individual charities are in actually meeting their stated goals.

Another exhibit dealt with what the museum described as The Really Big Questions. One of those questions was “why do we tell stories?”

And the answer offered by the Exploratorium is:

Many scientists believe that all humans tell stories. But why? When we tell a story, we’re sharing more than just the plot. Telling stories lets us share survival strategies, learn cultural practices and form closer relationships. Through stories people deal with complex or disturbing ideas and reveal their deepest thoughts and fears. Humans are born storytellers, and we can find a good tale in any situation.

“When we are immersed in a story, we become connected to its characters and feel what they feel. In fact, our identification with a character in crisis may let us learn new ways of meeting challenges and solving problems. But whether we call this feeling narrative transport or empathy, stories can arouse deep emotional responses in all of us.

So now I know why I write stories. Better yet, I have a hint as to what you may be looking for when you read them!

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com. Any comments below should be accompanied by the respondent’s full name and city and state of residence. Those living outside the United States may provide city and country.