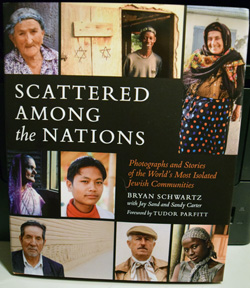

Scattered Among the Nations by Bryan Schwartz, Joy Sand and Sandy Carter; Weldon Owen publisher, Visual Anthropology Press, 251 pages, cover price $60.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –I’m going to rearrange the sequence of Bryan Schwartz’s narrative and photography book so that we can always travel toward the east, almost around the world, starting in San Diego and ending 16 stops later in Kangpokpi, India, close to the Myanmar (formerly Burma) border. While the longitude of the places we will visit will be in sequence, the latitude literally will be all over the map.

SAN DIEGO –I’m going to rearrange the sequence of Bryan Schwartz’s narrative and photography book so that we can always travel toward the east, almost around the world, starting in San Diego and ending 16 stops later in Kangpokpi, India, close to the Myanmar (formerly Burma) border. While the longitude of the places we will visit will be in sequence, the latitude literally will be all over the map.

While visiting five continents (North America, South America, Europe, Africa and Asia), Jewish readers will find themselves feeling at home, recognizing many customs that they too practice. Yet some customs, indigenous to the areas we visit, will intrigue Jewish readers. The book’s narrative, along with a rich assemblage of photographs, will help us feel that we are experiencing life in these communities. Some Jewish forshpeiz follows

Our first stop in Venta Prieta, Mexico. For San Diegans, this stop may feel very similar to what cross-border visitors have seen in Tijuana: People who once appeared to be Catholics but secretly practiced Judaism or believed themselves descended from and spiritually connected to people who were openly Jewish. As there has been tension between the new Jews of Tijuana and those from long-established families, we learn that in Venta Prieta, there is resentment about the attitude of the Jews of Mexico City, who consider the residents not to be authentic Jews. At the same time, people in this community are feeling uneasy with strict Orthodox Judaism which is being exported to their community.

Next, we stop in Trujillo, Peru, where Inca Indians have decided to convert to Judaism from Christianity after one of their leaders preached that Judaism, rather than Christianity, was closer to God’s word as expressed in the Bible. There is a cost to their religious beliefs. Jewish children often are picked upon in schools, not only by fellow students but also by teachers. Like many of the communities that we will visit, there is a great desire here to immigrate to Israel.

Moises Ville, Argentina, was settled by Jews in the late 19th century with the assistance of Baron Maurice de Hirsch, who created a fund to find agricultural homes for Eastern European Jews. Moises Ville was named in the Baron’s honor, because Moises (or Moshe) is his Yiddish/ Hebrew name. This is the town famous for “Jewish gauchos,” the cattle ranchers who supply beef to a meat-hungry nation. Its problem is that its youngsters, in search of an education and new opportunities, migrate to cities like Buenos Aires, and many don’t return except on vacations.

Obidos, Brazil is one of several locations along the Amazon River where Jews have established themselves as merchants. The population is dwindling, and those of a marriageable age have a problem: either they can marry a cousin (which genetically isn’t a good idea), or they can marry a Catholic (the religion practiced by most in the region), or they can move to Sao Paulo where there is a larger community.

Belmonte, Portugal, is a community with a long history of hidden Jews, who often were called “Marranos” (Pigs) by contemptuous people. While a good number of the town’s Jewish community are now openly Jewish, some prefer the old ways, which were built upon the need for caution in a country that once embraced the Inquisition and burning heretics at the stake. For example, when behind closed doors, a Torah was lifted from its hiding place, it would remain rolled and inside its mantle, in case it had to be quickly hidden from intruding authorities. A device for making matzo was cleverly constructed from roof tiles, so as not to raise suspicion.

Ourika, Morocco, in an area mostly populated by Berber people, is rich with legends about a local tsaddik, or wise man, named Rabbi Shlomo Ben Hensh, who crossed the North African deserts centuries ago to raise money for Jewish communities in Palestine. Attacked and wounded by thieves, he miraculously turned into a fearsome snake and prevented the brigands from stealing his possessions. Turning back into human form, but knowing he would die, the rabbi washed himself for burial, and vowed to be buried at whatever spot his mule stopped walking. To allow the tsaddik to reach Ourika before the onset of Shabbat (when neither man nor beast may carry objects), God stopped the sun in its path for several hours, not allowing it to set.

Sefwi Wiawso, Ghana, is an area where formal Judaism came into being when Aaron Ahomtre noted that Jewish practices described in the Bible were startlingly similar to those practiced by members of the Sefwi tribe. Among such practices are keeping kosher, menstruation separation, not working on Shabbat, and holding no funerals on Shabbat. Ahomtre and his followers decided that their long-ago ancestors must have been Jews who came either from Israel or perhaps Ethiopia.

Djerba, Tunisia, is an island in the Mediterranean off the coast of Tunisia. The Jewish quarter there is very ancient, with some families believed to have arrived about the time of the destruction of the first Temple; others after the Expulsion of Jews from Spain and Portugal. There is a tradition that the world’s oldest Torah is hidden in Djerba, and that a piece of the First Temple found its way to Djerba. Special ceremonies during Lag B’Omer attract tourists from Europe and the West. One of the customs is for women to place hard-boiled eggs with the names of unmarried girls written upon them along with warming candles, symbolic of the hope that the girls will find husbands and be fertile. Arabs and Jews still live alongside each other in Djerba, although at the time of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war many Jews fled the open hostility.

Oudtshoorn, South Africa, located on the African veldt, is a place where Jews, who originally hailed from Lithuania, for generations have made a very good living raising ostriches and selling their feathers and their meat. The Jews of Oudtshoorn hew closely to Orthodox practice, which means that while they produce ostrich meat, they never eat it because it is not kosher. Like the Jews of Moises Ville, Argentina, these ranchers worry about their children moving away to the big city.

Vinnystsia, Ukraine, is a community that is being regenerated in an area that once birthed the Chassidic movement. The Jews here survived the Holocaust, and endured the oppression of the Soviet Union. When Ukraine became independent, the open practice of Judaism began to sprout anew.

Rusape, Zimbabwe, has a Jewish community that started as a transplanted Christian sect from the United States. However, the more people studied the Bible, the more affinity they felt with Judaism, which had customs and beliefs paralleling some of those of the indigenous Shona culture.

Mbale, Uganda, is the home of the Abayudaya people, whose ancestors followed King Kakungulu, who first converted to Christianity in deference to the British colonial regime. Later, in an act of defiance, he tore the New Testament out of his Bible and declared himself a Jew. Thousands of his male followers underwent circumcision in a conversion ceremony. Jewish visitors from other parts of the globe gradually taught the Abayudaya more and more about normative Judaism. Hostility from Ugandan dictator Idi Amin forced many of the Jewish Abayudaya underground, but after he was deposed the community grew stronger. Three hundred Abayudaya were formally converted by Conservative rabbis from the United States in 2002.

Krasnaya Sloboda, Azerbaijan, celebrates Passover with foods that will make Ashkenazim’s mouths water. Typical dishes are a beef and potato stew called ashkana; fried spinach, eggs, beef and onions called khoyagusht, and kharosut (known elsewhere as charoseth), a mixture of apples, walnuts and wine. During Pesach, powdered sugar is banned, but not sugar cubes—apparently in the belief that forbidden grain might slip into the powdered sugar.

Bukhara, Uzbekistan, developed traditions during Soviet times of masking Torah learning. If two boys were at the home of their Torah teacher, and a visitor wanted to know what they were doing there, they would say “playing.” If only one boy was with the teacher, he would say that he was a “houseguest.”

Alibag, Maharashta, India is a community where many Bene Israel people lived before their migration to Israel. The Bene Israel have a malida ceremony in which they honor the Prophet Elijah with bowls of fruit and flowers, and special prayers and songs. Some favorite imagery is Elijah ascending to heaven in a golden chariot.

Kangpokei, Manipur, India suffers so many earthquakes that a tradition has arisen to run from a building with a prayer that means in translation “We are alive. We are well. We are the Children of Mannasse.” The people are known as the Benei Menashe.

San Diego Jewish World trumpets the motto that “There is a Jewish Story Everywhere.” The book Scattered Among the Nations helps to validate and illustrate the concept.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com . Comments below must be accompanied by the letter writer’s full name and city and state of residence (or city and country if outside the U.S.)