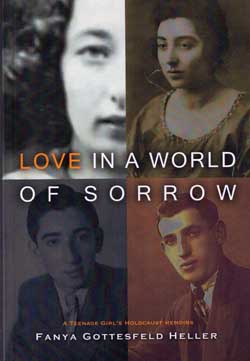

Love in a World of Sorrow by Fanya Gottesfeld Heller, Gefen Publishing House © 2015, ISBN 9780965-229-839-3l 252 pages.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –There are many authors like Fanya Gottesfeld Heller who tell their survival stories from the Holocaust at school assemblies and other forums. In San Diego County, the names of Gussie Zaks and Rose Schindler come immediately to mind. Each of the survivor’s stories is different, and all merit special attention. Heller lives on the East Coast, where she has had occasion to meet and be photographed with such political celebrities as Hillary Clinton, Margaret Thatcher, Antonin Scalia, Colin Powell, Chaim Herzog, Michael Bloomberg, Edgar Bronfman , Robert Dole, Norman Lamm, Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, Elie Wiesel, and Robert M. Morgenthau.

SAN DIEGO –There are many authors like Fanya Gottesfeld Heller who tell their survival stories from the Holocaust at school assemblies and other forums. In San Diego County, the names of Gussie Zaks and Rose Schindler come immediately to mind. Each of the survivor’s stories is different, and all merit special attention. Heller lives on the East Coast, where she has had occasion to meet and be photographed with such political celebrities as Hillary Clinton, Margaret Thatcher, Antonin Scalia, Colin Powell, Chaim Herzog, Michael Bloomberg, Edgar Bronfman , Robert Dole, Norman Lamm, Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, Elie Wiesel, and Robert M. Morgenthau.

In reviewing this memoir, reissued from 2005, I am mindful that it has received critical acclaim and even was the basis of a film narrated by Richard Gere called Teenage Witness: The Fanya Heller Story. Yet, I found myself troubled by Heller’s account, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there were a division of opinion on the points I will make, depending upon whether the reader is male or female.

Living in Skala, Ukraine, Fanya was just 18 when the Nazis invaded her town. A Ukrainian man 10 years her senior, named Jan, took it upon himself to protect her and her family, bringing them food, hiding them during roundups, and risking his life on numerous occasions. Jan evidently idolized Fanya, treating her with respect and caring, even nursing her through bouts of sickness. He was a member of the Ukrainian militia, and what he did elsewhere – whether he helped the Nazis or only pretended to – is left to our imagination.

After a year of being together under the most trying circumstances, Jan and Fanya became lovers. From today’s perspective, I suppose, one might wonder what took them so long; Fanya had depended on Jan who never let her down. It was natural that under such circumstances affection and sexual attraction would develop.

Yet, once the war ended, their relationship went sour. Fanya’s father disappeared and some people blamed Jan, who initially had come into Fanya’s life because of his respect and affection for her father, Benjamin. No proof is offered in the book that Jan had anything to do with Benjamin’s disappearance, but Fanya and her family chose to believe the rumors. They left town for a displaced persons camp, where Fanya was introduced by a shadchan to the Jewish man that she would marry.

Fanya’s memoir puts readers into a quandary. Throughout her narrative, Jan acts like a perfect gentleman, who is caring, protective, considerate and who always acts kindly toward her and her family at great risk to himself. He is not a Jew; she is; and this weighs heavily on her mind. With the rumors—perhaps planted by people who wanted to break them up—that Jan was in some way responsible for her father’s death, Fanya breaks away from Jan, and marries one of the first eligible men she meets thereafter. Jan, in other words, was unceremoniously dumped.

I can’t go beyond Fanya’s narrative to know whether there were other circumstances—some shred of proof about Benjamin’s death, or reports about Jan’s militia activities contrasting with Fanya’s experiences—that might indict Jan’s character. I only can go on what Fanya herself reported. And on that basis, I believe Fanya acted unfairly toward a man who saved her life again and again. Maybe other readers will disagree, and I would welcome their comments.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com . Any comment in the space below must be accompanied by the letter writer’s first and last name and by his/her city and state of residence (for those outside the U.S., city and country.)

From Michael Berenbaum:

As I read Donald Harrison’s review of Fanya Heller’s work Love in a World of Sorrow, a Yiddish phrase came to mind “a blemish the bride is too beautiful.” Harrison points out the blemish in Fanya Heller’s memoir: She is too candid, too revealing of the many shades of gray that were at the core of the struggle to survive. Yet, those of us who are non-survivors should be humbled. No less a figure than Elie Wiesel admonished us, “only those who were there will ever know.” The Talmud cautioned, don’t judge your friend until you have stood in his place” and common American wisdom suggest that we not judge a man until you have walked a mile in his shoes.” So I, who have read Heller’s work many times and even taught it, would not dare to judge her. I do judge the work — and respect it — as one of candor that told a difficult and unvarnished truth – and for this I am most grateful.

Michael Berenbaum

Professor of Jewish Studies

American Jewish University

Los Angeles, CA