-40th in a Series-

Exit 13 A, Spring Street, La Mesa, California – ‘La Mesa Village’

By Donald H. Harrison

LA MESA, California – In the quaint shopping village on both sides of La Mesa Boulevard stands a furniture and accessory store that identifies itself as “Mostly Mission.” A plaque further identifies the building at 8340 La Mesa Boulevard as the one-time home of The American Film Manufacturing Company, which was known by its symbol of a winged, flying letter ‘A.’ The plaque explains that the company produced silent films in 1911 and 1912 under the leadership of director Allan Dwan. A check of the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) reveals that among the numerous films Dwan made in 1911 was The Yiddisher Cowboy, although that one was made in Lakeside before Dwan moved to La Mesa.

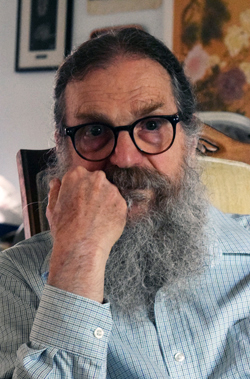

In the process of researching this one-reel silent movie — in which a brand-new Jewish ranch hand, who is made sport of by “real” cowboys, turns the tables and becomes master of the bunkhouse — I learned that a musician who plays cello with the San Diego Symphony and who also had one of the earliest klezmer bands in San Diego, Ron Robboy, had decades ago encountered the American Film Manufacturing Company in what became a combined quest to learn more about his cultural background, Yiddish literature, and the historic experience of the American Jewish left.

Robboy’s story began when he was rehearsing a work by Paul Ben-Haim in 1973 at San Diego’s Main Library, then located on E Street in downtown San Diego. Cantor Henri Goldberg, who came to San Diego in his retirement years, suggested to the ensemble that for the performance they dress as Israelis, which may have meant no dress code at all. However, tenor Howard Fried, who was performing as a vocalist, was wearing a Mexican guayabera, and joked that he would wear a similar shirt at the performance and come as a Jewish cowboy. The idea of a “Jewish cowboy” struck many of the musicians as funny, but thinking about it, Robboy wondered whether indeed there had been Jewish cowboys. Maybe the term was not such an oxymoron, he remembered wondering.

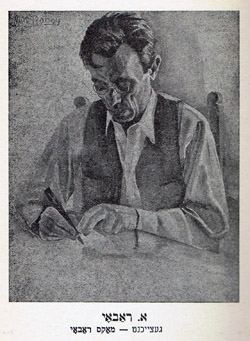

As he left the subsequent concert to go to his car, Robboy was hailed by an elderly, Yiddish-accented man who identified himself as Saul Stock. He wanted to know if the cellist was any relation to the Yiddish writer A. Raboy. “What did he write?” inquired Robboy. “Jewish cowboy stories,” Stock responded. The coincidence of Fried’s and Stock’s comments intrigued Robboy, but it wasn’t until a year and a half later that his odyssey germinated. One morning in the pre-dawn hours, he awakened from a dream and asked his then companion, Molly, “Whatever happened to Flying A gasoline?” She didn’t know but later, on that same day, she saw an advertisement in the San Diego Reader offering to sell a Flying-A Gasoline sign. Robboy drove from his home near North Park to Ocean Beach to purchase the 4-foot diameter sign for $10.

Why did he dream about ‘Flying A’? Robboy wondered. A friend and composer, Warren Burt, suggested that somewhere in his subconscious, Robboy was launching a quest to learn more about the writer “A. Raboy.” The funny thing is that Raboy’s first name, in English, was Isaac, but when he spelled it in Yiddish, it wasn’t the transliteration for “Yitzhak” but rather one for “Ayzik” starting with the Hebrew letter aleph rather than with a yud. The Aleph thereupon became the “A” in “A. Raboy.”

Subsequently, Robboy was alerted by another article in the Reader that the Flying A also was the symbol of the American Film Manufacturing Company, and that the company had made movies here. The article mentioned two films “The Yiddisher Cowboy” and “The Cowboy Socialist.”

The IMDb website, quoting a synopsis from Moving Picture World, describes the plot of that film directed by Alan Dwan as follows:

Ikey Rosenthal finds peddling a bum business in Wyoming. Consequently he is highly elated when John Darrow, foreman of the ‘X Bar’ outfit, offers him a job punching cows. He is fitted out at the ranch in chaps, spurs, sombrero, etc., and feels that he is a regular cowboy. On his first appearance in his new outfit the boys work their game of gun music on him and, in this instance, are treated to a genuine Yiddisher dance. Ikey is very angry, but bides his time until he can even up the score. He learns the work on the ranch and one day succeeds in roping a cow, thinking he has roped a steer. Payday the boys follow their time-honored custom and go to town to celebrate. Ikey, however, with true business instinct, remains at the ranch and, during the cowboy’s absence, gets out his old peddling pack and sets up a pawn shop in a corner of the ranch yard. The boys return from town broke and when Ikey shows them his pawn shop they decide to ‘hock’ their guns. Ikey gets possession of every gun on the ranch and then starts to do a little shooting himself. The boys scatter at his approach and the Yiddisher cowboy is monarch of all he surveys.

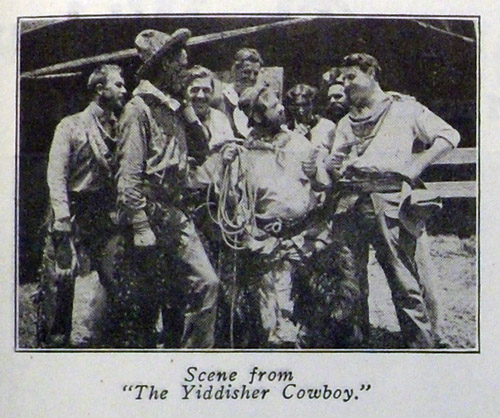

No copies of the movie are known to remain in existence, but in the same issue of Moving Picture World a still life photo from the movie was featured along with an advertisement that began: “’Yiddisher’ and ‘Cowboy’ do not jibe. There are complications uproariously laugh-provoking…”

In April 2011, one hundred years after the film was made, Robboy delivered to the Western Jewish Studies Conference in San Diego an analysis of the film in which he focused on the perceived “oxymoron” of a Yiddish cowboy.

On the one hand, Robboy wrote, there is

the cowboy, the weather-beaten icon of self-sufficiency: the leather-faced, rugged individualist; the emblematic strong silent type. Yes, the man of few words who knows how to live off the land, he is at home anywhere and everywhere on the land.

On the other hand, Robboy continued

there is the Jew, the pre-Zionist one, that is, the goles-Jew of Diasporic Exile; powerless, puny, pale-faced. And though he or she may be the world’s archetype for one who is at home nowhere on the land, he or she is anything but the man or the woman of few words.

Looking at the photo, Robboy suggested that it “reveals a short, stubble-faced outsider, hopelessly out of place among the threatening he-men surrounding him. His hat is too small, and his pants are too big, which taken together…would seem to symbolize his sexual inadequacy. In his confrontation with the cowboy to his left, he’s offering a paltry and tangled lasso in response to the cowboy’s six-shooter (one being the penetrating object and the other the potential receptacle.) The derby, baggy pants, and whiskered near-beard were conventions of the vaudeville ‘Hebe’ comic, an analog of the blackface entertainer, who was a legacy of the invidious American minstrel tradition in which (usually) white performers would mimic and exaggerate racial stereotypes of African Americans….”

A scholar who briefly considered The Yiddisher Cowboy in her book The Jew in American Cinema was Prof. Patricia Erens of the Communications Arts and Sciences Department at Dominican University. In a telephone interview, she characterized the film to me as one in which an underdog gains his revenge, a “Jewish revenge” story if you will.

Dwan was not a Jew, and his characterization of the Jew is one of someone who prevails by being a pawnbroker – a stereotype that might be considered anti-Semitic, according to Erens.

Robboy related that he interviewed Dwan by telephone in 1979, two years before the latter’s death. Dwan said he typically went to a location – in this case the hills behind the now defunct Lakeside Inn, where his company was based before moving to La Mesa – and would improvise a script based on the surroundings. For example, if he spotted a rugged cliff, he might have the hero –usually played by J. Warren Kerrigan—fight with a bad guy up there, then build a script around the scene for a 10-minute movie also featuring Pauline Bush, whom Dwan later married and divorced.

Asked how he came up with The Yiddisher Cowboy, Dwan wisecracked to Robboy that it was “in honor of Kerrigan’s nose.” Robboy didn’t take the snarky answer for fact; for one, Kerrigan played a ranch hand in that movie, not the Jewish cowboy – who was played by a much shorter man, not identified in the credits. Secondly, the size of Kerrigan’s nose was ordinary. And third, if Dwan had intended the film as a slur on the Jews, there was a much more likely target. Before joining The American Film Manufacturing Company, Dwan worked for a film company named Essanay—which stood for S and A, the initials of partners George K. Spoor and Gilbert M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson. Broncho Billy starred in 1903 in what is considered the first great silent western, The Great Train Robbery. But Gilbert “Broncho Billy” Anderson was a double pseudonym; in reality “Broncho Billy” was Anderson, and Anderson actually was Max Aronson, a real-life Jew who played a cowboy!

Robboy noted that Dwan went on to become a successful Hollywood director of such silent movies as Robin Hood with Douglas Fairbanks; and talkies like Heidi and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, both starring Shirley Temple; Suez with Tyrone Power and Loretta Young; The Three Musketeers with Don Ameche and the Ritz Brothers; The Sands of Iwo Jima with John Wayne; and Cattle Queen of Montana starring Barbara Stanwyck and future United States President Ronald Reagan.

*

Robboy’s research didn’t stop with the Dwan’s The Yiddisher Cowboy, far from it. He learned that in 1909 another film of similar ilk was made in New York State. In this one, by Bison Films, a Jewish peddler heroically saves a stagecoach under attack by Indians, but we learn it is only a dream; after a hard day, the peddler had fallen asleep against a wall on which there was a poster for a movie western.

Digging into A. Raboy’s life, Robboy learned that about the same time that the two Yiddisher Cowboy movies were being made, Raboy who had studied agriculture at the Baron de Hirsch school in Woodbine, New Jersey, obtained for himself around 1910 a job on a ranch in North Dakota, where utilizing his knowledge of animal husbandry he tended to the rancher’s prize stallion.

This experience was the basis for a Raboy novella titled Herr Goldenbarg (1914) in which a Jew from the East comes to work for a successful Jewish rancher and promptly falls in love with his niece. Robboy, who researched the novel, explained that this made the rancher happy because he wanted to pass on the ranch that he built to a Jewish son-in-law. However, it made the non-Jewish son of a neighbor very angry because he also had his eye on the niece. The success of the Jewish rancher also was a cause of envy, resulting in an outbreak of anti-Semitism. The situation was calmed when Goldenbarg gave a speech to his neighbors underscoring their common humanity. But not all the hopes and dreams of the rancher were fulfilled; his niece and the young ranch hand decided to start new lives as kibbutzniks in pre-mandatory Palestine.

The novella, written in Yiddish, was first published in New YHork with editions following in Europe and even South America, and was made into a play for the Yiddish stage in New York City. Joseph Green, who acted in that play, went on to become a Yiddish film producer, his works including Yidl Mitn Fidl in which the great actress Molly Picon posed as a man.

Later in Raboy’s career, he wrote an autobiographical novel, Der Yidisher Kauboy (The Jewish Cowboy, 1942), in which the plot closely resembled some of the experiences he outlined in Herr Goldenbarg. In this book, a Jewish ranch hand from the East makes himself invaluable to a wealthy non-Jewish ranch owner, who nevertheless seems to be pushing him to leave his employ and to file for a homestead. This makes the ranch hand uneasy—why should the man be so anxious to lose his best employee? Perhaps, the rancher was aware that his wife, like Potiphar’s wife who threw herself at the biblical Joseph, had been making sexual advances toward the Jewish ranch hand, or perhaps the rancher’s eagerness to be rid of the ranch hand was because of something more sinister. The novel did not resolve the issue; it ended with the ranch hand returning to the East to resume his old life, even as Raboy did.

After reading the novel, Robboy – who is of no known relation to Raboy despite the similarity of their names—decided to travel to western North Dakota to see if he could find any document indicating that Raboy had planned to become a homesteader. He couldn’t find any such document, but he found something better. By comparing places and descriptions, he learned that the fictional rancher Hildenberg in the novel was based on a real-life rancher named Caldwell, who owned lots of property, but was murdered along with his mail-order bride by a ranch hand.

Meeting with a centenarian who lived at a ranch that adjoined Caldwell’s, Robboy heard stories about Stark County, North Dakota, that paralleled stories that appeared in Raboy’s Yiddish-language book, which the neighbor never read, nor had he ever heard of Raboy.

After Caldwell was murdered, law enforcement officers found disturbed dirt in his barn. When they dug in the barn, they found the bodies of numerous immigrants who had worked briefly for Caldwell, had homesteaded, and then “disappeared.” Their homesteaded properties subsequently were purchased at auction by Caldwell. From this Robboy concluded that had A. Raboy stayed in North Dakota, instead of returning to his family on the East Coast, his might have been one of those bodies.

The question of why the ranch hand killed Caldwell and his bride remains a mystery. The perpetrator was institutionalized for life in the North Dakota State Hospital, and nothing in available records indicated that he had ever homesteaded. So there is no evidence that it was a matter of self-defense against the scheming Caldwell.

Remembering Raboy’s story, Robboy suggested a possible solution to the mystery. Perhaps, he said, the mail order bride had made a pass at the ranch hand, even as she had made one at Raboy, and in he ensuing fight Caldwell was killed, but perhaps not before taking the life of his bed-hopping mail-order bride.

The odysseys of Raboy and Robboy were documented by the latter in the 1979 Der Yiddisher Cowboy — A Film in English, co-produced by Robboy with his friend Warren Burt.

From Spring Street exit proceed on Spring Street to left turn on La Mesa Boulevard.

Next: Grossmont Center

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. You may comment to him at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com, or post your comment on this website provided that the comment is civil and that you identify yourself by full name and your city and state of residence.

Pingback: Travel news: New Gilt site, Downton show, Taipei design - San Diego