-58th in a series-

Exit 30, Tavern Road, Alpine, California: Dream Rider Equestrian Therapy

By Donald H. Harrison

ALPINE, California – A head-on automobile collision near her home in this mountain community alongside Interstate 8 put Catherine Hand into a wheel chair and ended her first career as a set and costume designer for major productions of the ballet and the opera. But riding a horse got her out of her wheelchair and into the profession of therapeutic horsemanship—using horses to help people overcome both physical and mental disabilities.

ALPINE, California – A head-on automobile collision near her home in this mountain community alongside Interstate 8 put Catherine Hand into a wheel chair and ended her first career as a set and costume designer for major productions of the ballet and the opera. But riding a horse got her out of her wheelchair and into the profession of therapeutic horsemanship—using horses to help people overcome both physical and mental disabilities.

No longer needing a wheelchair, Hand today walks around the arena adjacent to her home on Anderson Road, offering instructions and encouragement to children with disabilities as well as to survivors of breast cancer for whom bonding with horses can be a pathway to wellness.

With the permission of 16-year-old Alise Yamamoto’s mother, Samantha, I recently attended an hour-long session designed to improve the girl’s sense of balance while strengthening her memory and ability to follow instructions.

“My daughter is developmentally delayed,” Samantha Yamamoto told me. “She speaks in one and two words, not even sentences. Sometimes, if prompted, I can get her to speak in full sentences. She is orthopedically impaired, and she is about a third-grade level in reading. Her comprehension and receptive language is there, but it is very hard for her to get across what she needs. But you talk to her and she understands every word.”

Alise’s brother Ryan, 11, is a natural athlete, good at golf, good at soccer, and very comfortable on a horse. On the day that I visited, he rode in the same arena as Alise – a first—and the experience of doing the same thing as her brother obviously delighted Alise. “I think that is why she is so giggly today,” he mother said.

Hand, a Jewish American who learned many of her teaching skills at the Wingate Institute, Israel’s National Center for Physical Education and Sport located in Netanya, set out a program for Alise and Ryan that included, among other activities, performing stretching exercises on their horses; reaching for rings on posts alongside the arena and depositing them into low buckets; knocking a ball into a net with a field hockey stick, and leaning over to withdraw letters from a mailbox.

Alise, who had been riding off and on for nearly 10 years, was aboard a 21-year-old mare named “Ginger Sparkles.” Previously she had ridden Hand’s personal horse, the late “Treasure.” Ryan was mounted on a young mare named “Daisy Mae.” They performed their tasks accompanied by their favorite music. For Ryan and his mare, it was Ennio Morricone’s theme for the movie The Good, the Bad and the Ugly that starred Clint Eastwood, while for Alise, it was Carmine Coppola’s theme from the movie The Black Stallion that starred Kelly Reno.

Turning on a boom box with The Black Stallion tune, whenever it was Alise’s turn to perform, was one of the jobs that the children’s mother volunteered to do during the hour-long session in this picturesque setting.

Other volunteers included two teen girls who are approximately the same age as Alise – which gladdened Alise’s heart – and four local women who were attracted by the opportunity to do volunteer tasks that involve helping a child with special needs and working with horses. The girls were Katelyn Mangum, 16, and Bea Wygant, 15, while the adults included Bea’s mother, Christina; Stacey King; Marilyn Bach and Nancy Edwards. A couple of them told me they learned of the volunteering opportunity through nearby churches, while another saw a notice on a bulletin board at the Alpine Community Center.

The volunteers walked alongside the young riders; made sure their horses were positioned properly near a stand for mounting and dismounting; modeled the stretching exercises; and generally offered encouragement to the riders under Hand’s watchful eyes. You could include Ryan in the corps of volunteers as well because he demonstrated on a barrel the exercises that Hand teaches her clients to familiarize them with the muscle groups needed in horseback riding.

Hand told me that “Alise started coming here when she was 6 years old. She had fused feet requiring multiple surgeries and wore leg braces before she was brought to Dream Rider Equestrian Therapy, the non-profit organization that Hand heads. “She had to be carried here and was wearing diapers,” Hand said. “After six lessons she was no longer incontinent. The reason for that was that I had her doing exercises on the horse that stimulated the nerves in the pelvic area, awakening her sense of when she needed to go. Before that she didn’t have that. She was non-verbal but responded to music. In the womb she had Baby Einstein played for her, and she loves “Fur Elise” by Beethoven.

“At the age of 13, Alise experienced a major setback when it was determined that her skeletal frame was not developing properly and she had to spend a year in a full body cast,” Hand said. “We have been working on developing her flexibility since that operation.”

Alise initially “couldn’t button her clothes, tie her shoelaces or do anything with her hands, and she didn’t have to because her family took very good care of her. Now at 16, she is riding, controlling the horse, holding the reins, making the horse turn to the right and turn to the left. In order to exercise her brain, we do a lot of left and right, left, right, left, right to stimulate both sides of the brain, to cross the midline between the two hemispheres in order to get the communication going.”

Though a typically developing pre-teen today, Ryan had difficulty adjusting earlier in his life to all the attention that Alise required from their parents. According to his mother, he was quiet, hard-edged, and uncommunicative, but like his sister, he benefitted greatly from therapy with horses. He came to accept that although younger, he was Alise’s “big brother” and today cheerfully accepts extra duties.

I asked Samantha whether she felt the therapy with horses had helped her daughter physiologically. She said it has made a difference in “the way she moves and walks. She gets off the horse and she is more comfortable in her own skin. She can move better. She has had several orthopedic surgeries, and this is helping. It has been the best thing for us.” Furthermore, “she is more verbal on the horse, more animated, although she is not usually so giggly. When we come home from a lesson, she will be talking in the car, not full sentences, but more engaging. It just brings that out in her. She is excited.”

As the lesson ended, the children reached into the mail box and found addressed to them letters with presents inside – a blue ribbon and stickers for Alise and a “million horse dollar” bill for Ryan. Once the Yamamotos and the volunteers headed for their respective homes, Catherine and I sat down for an interview in which she told me of some of the high points of her life.

She said that up until age 6, she lived in Toronto, Canada, with her mother, the former Bertha Shoichet, who came from a shtetl in Poland, and father Louis Coldoff, an aspiring sculptor. Later the family moved to Orange County, California—a culture shock for her mother who had been a labor organizer and felt out-of-place in the politically conservative area to which they relocated. Her mother and father were divorced before Catherine went off to study music and literature at UC Berkeley. She married and divorced young—her first husband George Hand, and father of her son Peter, was related to the famed jurist Judge Learned Hand and was a descendant of immigrants who came to America on the Mayflower. She said she retained the surname Hand because “it suited everything about me. I always loved my mother’s hands. She was a very distinguished woman, but she had the hands of a stevedore. She worked hard all her life. I don’t have those hands; I have little hands. I thought ‘I am going to work so hard in my life someday my hands will be like hers.” Aged 73 in 2015 when I interviewed her, her hands still were not particularly rough, but she said, “I think I’m getting there.”

She graduated from UC Berkeley and moved to Pennsylvania where her then-husband taught history at a private college for boys. There she became involved in helping to paint sets for the drama department. In the summer of 1967 she went to New York for an opportunity to work under New York Public Theatre director Joseph Papp as an apprentice at the New York Shakespeare Festival in Central Park. In New York City, she met actor Stacey Keach and set designer Ming Cho Lee, each of whom positively influenced her career. Returning to the San Francisco Bay Area, her work with Ming Cho Lee helped win her a job as a stage and costume designer for the Marin County Shakespeare Festival.

“The designs got great reviews so I was on my way,” she reflected. “I met Davis West after being hired as a junior designer and draughtsman by the San Francisco Opera. When I saw opera paintings for the first time, I was so excited by the scale and grandeur of these paintings, I had to learn to do that… and I did.” Fifteen years after West and Hand began working together, they were married.

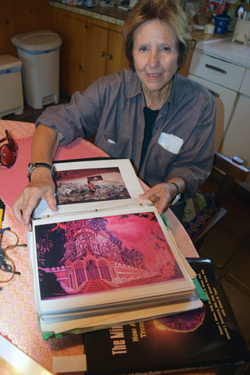

Hand flipped through a photo album in which she showed me various backdrops that she had designed for opera and ballet, pausing lovingly over the designs for The Nutcracker, which instead of in Bavaria or Victorian England, she set in an imaginative interpretation of Russia, in which the onion domes of the Kremlin were transformed into strawberry finials atop a strawberry shortcake Kremlin wall. This was the era of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, and little jelly beans fly through the painted sky. Other backdrops included a Doctor Zhivago-esque dacha and a horse and carriage reminiscent of one that had been painted on a lacquer box her mother had brought back from Russia in the 1930s.

During the early 1980’s, Hand traveled extensively, even moving to Israel for an extended period, where she sampled kibbutz life and worked in Israeli television as a set designer. Career opportunities persuaded her to return to California, where Hand’s reputation for designs reached the ears of rock singer Jon Bon Jovi. He asked her to design a set of 40-foot high curtains to drape in front of the large speakers he would use in his group’s 1989 appearance at a “peace concert” in Moscow. She said he asked for a design showcasing famous American movie gangsters as portrayed by actors Edward G. Robinson, George Raft, Jimmy Cagney and the like. Bon Jovi sent Hand a deposit check, which she picked up at her post office box in Alpine. On the way home, her car was hit head-on by a car driven by a speeding teen driver. The force of the collision broke her jaw as well as both ankles. She thought her productive life was over.

She said she messaged Bon Jovi that she would have to send back his deposit; she didn’t believe she would ever design another set. But the singer demurred. She could use her hands, couldn’t she? She could still see? Keep the deposit, he said, and work on it when you can. He asked her to send him faxes showing the progress of her work. So with the help of husband Davis West, she placed a door on top of a couch and, wheeling alongside the couch, created a gangster collage that Bon Jovi liked and subsequently had transferred to lightweight scrim curtains through which sound could travel and that could be seen, or seem invisible, depending on the lighting.

Hand said remaining in a wheelchair for months was physically and psychologically painful for her. When you are in a wheelchair, she said, “people will shout at you because they think you are deaf. They will stoop very low because they think you can’t see well, and they will speak in baby talk because they think you are simple-minded sitting down there. I made up my mind after that experience that I would never talk to anyone who is handicapped that way.”

Although her ankles were held together with plates and screws “and still are” Hand said “I had to get out of the wheelchair. My husband would bring the horse to the front door and wheel me down a ramp, and lift me onto the horse, and let me walk up the mountain behind our house on the horse. What that did was stimulate the spine; it kept me from atrophying. It built up the muscles in my legs so that I could support my weight despite the damage to my ankles.”

She would ride the horse and then be lifted off by her husband. “One day, I said ‘don’t put me in the chair. I want to try to stand.’ I did, and I was able to stand. And the next day, after he put me down, I said ‘I want to take a step.’ It was one baby step at a time. When I could finally walk, all I wanted to do was run. And I went back to Israel (Netanya) to take a two-year-course to study therapeutic riding.”

In the meantime, Hand and West decided to divorce, agreeing that their marriage was a mistake. “His 1950s idea of a wife was not me,” Hand said later. “We were better off as colleagues and best friends.”

In 1995, while still in Israel, West had a stroke, and Hand flew back to Alpine to take care of him and to remarry so she could have the legal right to speak for him to obtain treatment. “We were still best friends,” she said. Besides, he had taken care of her after the accident, and now it was her turn to reciprocate.

“He couldn’t paint, he couldn’t talk, he was paralyzed,” she said. “I discovered that if music was playing, and it was a song that he knew, he could sing the words of the song, and so we started to sing to each other. I sang to him to the tune of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” a question, and he sang back to me his answer. There are two parts of the brain where speech resides: the left-hand hemisphere where we have the spoken word, which was damaged, but on the right hand side of the brain, there are words, if they are connected to music. That is why I use music in the horse therapy program.”

Singing questions to her ex-husband “triggered an awakening in the brain and the synapses began to regrow in his brain, eventually to the point where he could read and paint again but he still had to do it with one side of his body. He could drive a car, but he had to pass the (usually written) test with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers, which I asked them to do. He was rehabilitated with the music” and had several productive years of life before he died.

Hand went through another crisis of her own in 2007 when she had a mastectomy following the discovery of breast cancer. Hooked up to an oxygen tank, on hospice, weak, and believing she would die, she wheeled herself out to her horse, “Treasure.”

Forcing herself to stand up from the wheel chair and to remove the oxygen mask, she climbed up a mounting block and lay down backwards upon her old friend Treasure’s back. “As I lay there taking shallow breaths, I felt her taking deep breaths, her barrel expanding and contracting as she inhaled and exhaled,” Hand wrote in an article prepared for a therapy journal that she shared with me. “Instinctively, I matched her breathing. I stayed that way for about a minute. I pushed myself up from her back and inexplicably discovered that I could breathe on my own and was able to walk back to my house without using the oxygen tank.

“The next day the hospice nurse came to take my vital signs. Amazed, she said, ‘all your vital sign readings are normal. What have you done?’ I answered, ‘I went out to say good-bye to my pony, lay down on her back and hugged her.”

Hand and the nurse compared the phenomenon to a premature baby with respiratory and circulatory problems being laid on its mother’s chest. “Through skin-to-skin contact, nerves in the skin transmitted the mother’s respiratory rate and heart rate to the infant brain to regulate and kick-start those systems thus eliminating the need for incubation.”

Having survived, Hand and her therapy horses work with other breast cancer patients. She explains her work in a pamphlet entitled Your Guide to Equine Assisted Rehabilitation for Breast Cancer Patients, which can be ordered from her at catherineh@prodigy.net

Once-a-week lessons over a six-week period cost $210 paid in advance. Because lessons require considerable advance set-up time, and coordination of volunteers, this fee is non-refundable, Hand said. Dream Rider Equestrian Therapy seeks tax-deductible donations for clients who can’t afford that amount, and also seeks donations to defray such expenses as insurance and the $4,000 annual cost of maintaining a therapy horse. Those wishing to donate may do so via the website, www.dreamriderequestriantherapy.com, or by check to Dream Rider Equestrian Therapy in care of Hand at 543 Anderson Road, Alpine, California 91901.

*

From the I-8 exit at Tavern Road, turn left to Victoria Drive, and continue to a left on Anderson Road. The horse arena may be visited by appointment only. Hand may be reached via info@dreamriderequestriantherapy.com or 619-445-2576.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com