By Goldie Morgentaler

LETHBRIDGE, Alberta, Canada– My mother, Chava Rosenfarb, was liberated at Bergen-Belsen by the British army on 15 April 1945. At the time, she did not know that she was free because, like many of the inmates, she had typhus. The British took her to a makeshift hospital on the grounds of the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp and there she slowly recovered.

The British encouraged a return to normality after the horrific conditions they found in the camp by providing venues for concerts to be staged by the former camp inmates. Once recovered, my mother, her sister and their mother – my grandmother was one of the few older women who survived the war – went to one of these concerts. Waiting for the show to begin, my mother noticed a British soldier sitting alone in the row in front of her. She wondered how he would understand what was going on, as the concert was in Yiddish and she assumed – correctly as it turned out – that he was not Jewish. She tapped him on the shoulder and offered her services as translator. Her English was rudimentary, but good enough to start and maintain a conversation because by the end of the concert she and the soldier had become friends.

Where my mother learned enough English to communicate with the British soldier is a mystery I will never solve now that she is gone. She was born in Lodz, Poland and educated in Yiddish, Polish and German, but not in English.

Who was this out-of-place soldier who decided to spend his free evening attending a Yiddish variety concert, despite knowing that he would not understand the language? His name was Douglas Jensen and he was the youngest son of a baker from Sheffield. Before being drafted he had trained as a graphic artist, an occupation to which he would return after the war. Douglas was a shy man of moderate height, athletic and good-looking with a snub nose and pale blue eyes, but reserved – very English, my mother would say. Despite his shyness, he had an eye for pretty women and my mother, even with her hair shorn, was a beauty.

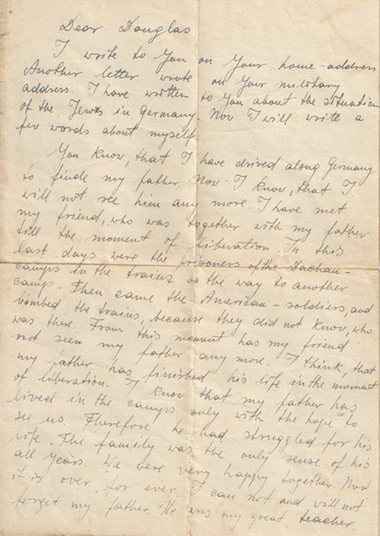

They started exchanging letters as soon as he was posted away from the camp. Her first letter to him is dated 5 June 1945, less than two months after her liberation. Not surprisingly, it is about the nightmare she had just lived through:

“I remember that a year ago I was still in the ghetto. A cold and dreary day. We have no coal for fire to warm our bodies. We are hungry and we have not to eat. We are so weary, so tired of our hopeless, senseless life. I am lying in the bed and with stiff fingers I am writing my poem. I’m no more in prison, I am no more a girl of a poor, humiliated, insulted nation. I am a victorious free soul. Happy moments!

“Now I am alone. My good friends – they remained in Auschwitz. It was the longest and darkest year of my life. Now is that terrible year past. The English army has freed us from the murderer’s hand. In this time I met you. You have offered me the door to the world. Thank you. You often asked me why I am smiling. It was because I was remembering the good old time, when I walked with my friends, hand in hand. Then it was good to be. Now I have nobody.

“But the darkness has not completely returned. I walk each evening in our wood near the camp. And when it rains I stand under the trees and smile. I have the sun in my heart, the wind in my hair and the rain in my eyes.”

In another letter, dated 28 October 1945, she tells him that she has learned of the death of her father, one day before the liberation, when an American bomb struck the train on which he and other Dachau inmates were being transported by the Nazis deeper into Germany. She writes: “I cannot find freedom for my weeping soul.”

Occasionally, a note of exasperation enters her letters that illustrates the distance between the survivors, struggling to return to normality, and the rest of the world. She feels that Douglas, despite having seen the conditions in Bergen-Belsen with its starving, diseased inmates and ubiquitous mounds of dead bodies, does not fully grasp what she has just lived through, nor the sense of displacement and homelessness that she feels. “How can you expect me to go back to Poland, where even now we have heard of a massacre of Polish Jews? I am a Jew and I am proud that I belong to this unlucky but intelligent nation. I don’t want to go to a country where I am a citizen of the second category.”

My mother’s early letters to Douglas hint at a failed romance. She is flirtatious at first, but that tone changes when my father appears in the camp. My parents grew up together, sat on the same bench at school, won the same prizes, were high school sweethearts and hid together with their families in a secret room when the Nazis liquidated the Lodz ghetto in August 1944. The entire group was caught and transported to Auschwitz, where the men were separated from the women; my father and grandfather were sent to Dachau. Until my father arrived at Bergen-Belsen looking for her, my mother had no idea that he was alive. It was he who brought the news of her father’s death.

Time passed. The romance may have cooled, but the friendship did not. Douglas had a gift for friendship, especially for friendship with women. During all my mother’s postwar wanderings, until she made Canada her home in 1950, Douglas sent her newspapers and books. He sent her a gilt-edged copy of Shakespeare’s plays, which she cherished her entire life and which I still have. He sent her his drawings, usually illustrations of poems, including a lovely watercolor illustration of William Blake’s The Sick Rose that she kept in her work room until the day she died. In 1948, after she published her first book of poetry, she was invited to London to give a reading at a Yiddish literary soirée. Douglas accompanied her, although he did not understand a word of what was said. Every year, he sent flowers on her birthday including her last birthday, 11 months before she died in 2011.

Not all my mother’s letters are as dramatic as the ones she wrote right after the war. But they all trace the lineaments of her life, and taken together they form an autobiography in letters. Unfortunately, I have only her side of the exchange. I have not found Douglas’s letters to her.

For 65 years, my mother and Douglas kept up their correspondence; she in Canada, he in England. She announced the birth of her daughter, then her son; he announced his marriage to a fellow artist. She sent him all her Yiddish publications and he advertised in the British press for someone who could translate so that he could read them.

Then, strangely, their marriages fell apart at the same time and for the same reason – the infidelity of their respective spouses. One day my mother impulsively bought a ticket to England and stayed with Douglas for several weeks. She made him chicken soup, tended his house and wrote poetry. They wandered around London when he was not working, went to plays and flower shows. I would like to think that they became intimate, but I doubt it. They were both bitter about relationships then; and romance can poison friendship. But what do children ever know of their parents’ sexual lives? What I do know is that my mother returned to Canada, to her children and her home, but not to her husband.

A few months after that encounter, she wrote to Douglas: “How good that we can cry on each other’s shoulders! Douglas, tell me what is in your heart. In England you let me glimpse your frightening loneliness, which you are trying to deepen still further, because, you said, animals hide when they are wounded. But we animals are also human. I too feel like hiding, but there is nothing more meaningful for me than contact with people close to my heart.”

When I was old enough to travel on my own, my mother insisted that I look Douglas up when I visited England and she wrote to tell him that I was coming. I was 21 and newly graduated from college. I was sitting on a wall outside my London B&B when I first laid eyes on this man about whom I had heard so much. He was white-haired by then, still spry, very polite, very reserved, and very witty in an understated English way. He showed me around London. He took me to the theatre. He let me watch as he drew his animated cartoons, a labor-intensive process in the days before computers. He apologized for not offering to let me stay at his house, but he lived there alone and it wouldn’t be proper. This was in the early 70s, and with the smug superiority of youth, I found his anxious respectability very quaint.

After that, whenever I went to England, I visited Douglas, and, in the end, I did often stay at his house. My mother too visited Douglas, sometimes with her second husband, an Australian travel agent. Douglas never remarried, not even after the premature death of his ex-wife, whom he always hoped would return to him. All his life, he was a recluse, a man of deep feeling and profound reserve, who mistrusted people in general, but relaxed in the company of women. He was athletic and, until the age of 80 when back problems made it difficult, he liked to go for day-long hikes in the Yorkshire Dales, where he had moved after he retired. But my mother’s worries about him cutting himself off from human contact were not unfounded. After he retired, he lived alone in a cottage in a tiny village in Yorkshire, far from the nearest town. He was, he claimed, a contented recluse, surrounded by his books and paintings.

He died alone in hospital, not far from his cottage. He had just turned 95. He had no children and as he was the youngest of his siblings, they had all predeceased him. I learned this from the solicitor who called me, in November 2012, to tell me that Douglas had left everything – his money, his paintings, his house and its contents – to me. In Douglas’s house, after his death, I found all the letters that my mother had written to him over the years, as well as copies of her books in Yiddish and in English translation. He appears never to have thrown out a word she wrote.

So I come back to the letters and the iridescent line they trace between the past and the present. In those letters I can hear the voice of my mother as a young woman, full of pain at the loss of all the people she had loved in her youth and of the irretrievable life that she had known before the war. And I can hear her as a new immigrant to Canada, feeling her way through the maze of the alien world in which she found herself, apologizing for her poor English. I can hear her as a middle-aged matron boasting about her children’s accomplishments. And I can hear her as a wronged wife in despair over the breakup of her marriage. Most of all, I can hear her as the writer, discussing her books, proudly proclaiming, “I love to write!” and ending her letters to Douglas with the peremptory, “Jensen, write to me!”

As for Douglas, he is everywhere in my house. His self-portrait hangs over my fireplace, his hand-drawn birthday cards decorate all my bookshelves, his paintings hang on my wall.

I was born in Canada and have lived a comfortable life there. I have never been poor, gone hungry, lost friends to war, experienced persecution, seen people murdered before my eyes. Yet the dark shadow of the Holocaust has hovered over all of my life. Sometimes, however, that shadow lets through a ray of sunshine.

My mother’s friendship with Douglas, immortalized in the form of letters, has been passed on to me as a gift from the past to the future. From youth to middle age to old age, they moved through life together, separated by an ocean, by different countries, backgrounds, faiths and political outlooks, but always in sympathy. I am on the periphery of their story and yet I am its beneficiary, the heir to a life-long friendship that arose out of the ashes of genocide and devastation long before I was born.

*

Preceding was originally published in The Guardian. It is reprinted here with the permission of the author, who retains the copyright. Comments intended for publication in the space below MUST be accompanied by the letter writer’s first and last name and by his/ her city and state of residence (city and country for those outside the United States.)