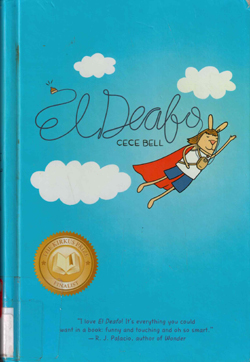

El Deafo by Cece Bell, color by David Lasky; Amulet Books; © 2014; ISBN 978141-9712173; 233 pages plus a note from the author; price not listed.

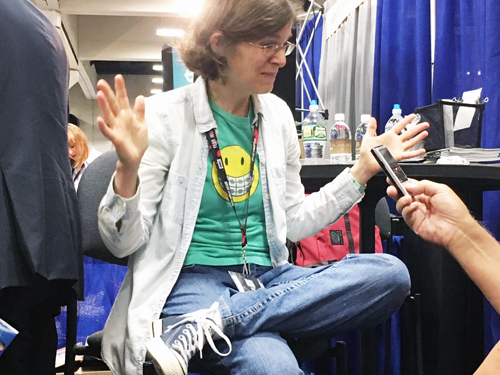

Story by Donald H. Harrison; Photos by Shor M. Masori

SAN DIEGO — Written for elementary and middle school audiences, El Deafo tells the story of author Cece Bell becoming deaf at the age of two, her visits to the audiologist, the molding of hearing aids for her; the limitations of the hearing aids; her assignment to a special class for deaf children, who were just like her, and later, the development of a special transmitter that her teachers could wear, so that Cece, wearing a receiver on her chest, could be mainstreamed in a neighborhood school.

Like most children, Cece wanted her classmates to like her, but sometimes that meant putting up with annoyances. One overbearing child treated her like an assistant; another slowly articulated each word – syllable by syllable—whenever she talked to her. At last, she found a neighborhood friend, a year younger, with whom she was able to play normally, but after Cece had a childhood accident, in which she bruised her eye, her friend, with whom she had been playing, was overwhelmed with feelings of guilt and avoided her.

The transmitter that her teachers wore proved to be Cece’s passport to popularity. The teachers were unaware that its broadcasting range covered the entire school and beyond. Thus when the teacher left the students on their own for quiet study, Cece could hear what the teacher did thereafter and could alert her classmates when the teacher was about to return to the class room. So while the teacher was away, the pupils would play, but at the moment she opened the door, they were all quietly studying—much to the teacher’s surprise and delight, and to the enhancement of Cece’s reputation.

Cece also could hear her teacher talking to other teachers in the lounge; giving a disciplinary talk to a fellow student, and even going to the bathroom. Except for the latter, which made her giggle, she kept such information to herself.

Instead of thinking of herself as disabled, Cece began to envision herself as a super hero – El Deafo! – whose unusual, technology-assisted hearing powers could be extended to the games she could play with other children. A cute neighbor boy, whom all the school girls had a crush on, took a liking to Cece, much to her delight.

Bell draws herself, as well as the other characters in the book, as having big rabbit ears. Hers had cords dangling from them, which connected her hearing aids to her receiver.

*

At the annual Comic-Con in San Diego, I had the opportunity to interview Bell, whose book had received the 2015 Eisner Award as the Best Publication for Kids, 8-12. She had me put around my neck a special microphone that would help her hear my words, while reading my lips. Following is a slightly edited transcript of our interview:

Q. Well I expected you to have rabbi ears.

A. Yeah,well most kids do. I wish I did

Q. Why do your characters have rabbit ears?

A. The book is very much about hearing right and hearing loss, and so the rabbit has giant ears, really good hearing, so I wanted to make a visual metaphor for feeling like the only rabbit in a whole school of rabbits whose ears don’t work. And then visually it was much better to have – you know in real life the cords that I wore with my hearing aid just went up the sides of my head, but in the book getting to draw them over my head makes them that more visual for them – which is much closer to how I felt, very conspicuous, everyone looking at me. So that was probably the main reason.

Q. Was writing this book cathartic for you?

A. Yeah, it was! It was my attempt to finally own up to the fact that I was deaf. It was really hard for me to tell people that. It felt really good to have a thick calling card, ‘Hey do you want to know more about this and about me?’ and so it has been very empowering for me, just to get it out.

Q. How so?

A. For one thing, it has just made me feel a lot better about being different, and meeting a lot of people who are just like me because of the book and so in meeting people just like you – ‘Oh, you’re doing just fine; I’m doing just fine.” — it was a good boost.

Q. You have had a successful and interesting life before this book was published.

A. Yes, I do a lot of picture books and early reader books that aren’t necessarily graphic novels but lots of illustrations.

Q. When did you decide to write this book and what was your motivation?

A. I have a specific answer for that. I had been doing picture books for a long time and not really addressing that fact because I didn’t need to. But I had a really awkward interaction with a grocery store cashier, and she was very – just really really rude to me. In large part when you can’t hear somebody, they get frustrated with you , and instead of being more helpful , they turn into (inaudible) – and that is what she was doing. So it just really upset me, and I never during that interaction said, ‘hey lady, I am deaf; you’re going to have to live with it, and help me out here.’ But I never said those words because I wasn’t comfortable with it. So later, I got really angry with myself for not speaking up about it. That was kind of the motivation for this book…. You know what, it was time to tell this story.

Q. Can you remember that conversation in a little more detail?

A. For me, when I go to the grocery store , I have some things memorized – what they are going to say; they usually say “paper or plastic” and “credit or debit” and “did you find everything okay.” Well she was saying different things that I wasn’t ready for, and every time when I simply didn’t hear her, or misunderstood her, she would say things along the lines – just repeating herself but very rudely. ‘I SAID THIS’ – and at the end of the whole thing I was so flustered that I forgot my receipt and I was pushing my buggy out to my car and she actually followed me and ran after me and yanked on my sleeve, and shouted: ‘YOU FORGOT YOUR RECEIPT’ and that’s when I lost it –uh wah – I actually cried all the way home; I was so angry. I never got around to speaking up.

Q. In what city did this occur?

A. This was Blacksburg, Virginia, where Virginia Tech is.

(The book) was sort of revenge; it didn’t actually start as a book ; it actually started as a blog, and the blog was more for adults to read. It was about my current pet peeves about conversation problems I had as a deaf adult. But then I started to write a part about how I became deaf and what that was like and then a friend of mine read that and said, ‘oh man, you need to be saving this up for something else’ and I was reading Reina Telgemeier’s book Smile (about a girl whose broken teeth left a big gap in her mouth) around the same time and I thought ‘oh man this is the perfect medium for this story because of the speech balloon and being able to use the speech balloon to show what I was hearing or I wasn’t hearing.’

Q. In your book , you instruct us about some of the things we don’t have to do, or shouldn’t do, when talking to someone who is deaf. You don’t want us to ar-tic-u-late? (draw out each syllable)

A. Right, that is a big one

Q. And you don’t want us to shout

A. Right..

Q. And these are things that people commonly do, I suppose.

A. Right

Q. Are there any other tips that you would pass along?

A. If you are a man, shave your beard and shave your mustache – get rid of them! That would be one. Speak to them the way you do normally, and then you make adjustments afterwards if you feel that person needs it. Sometimes I will have to ask ‘Can you repeat it? Can you speak a little louder? Slow down. Speed up!” But the articulation thing, it just makes you feel like you’re really stupid. Another one would be if you speak with your hands, don’t cover your mouth while you speak. Eating is okay, I can read lips through that.

Q. This wasn’t only a book about deafness; it was also a book about a young girl finding her way and winning acceptance, and that also seems to be an important story. But not everybody is going to have a microphone that will hear the teacher while she is returning to class and be able to alert all the kids. If you were going to be an adviser to a young girl or boy who was deaf and was trying to mainstream in class, what would you tell them, since they can’t exactly follow El Deafo’s example?

A. I would mostly say not to be ashamed of the technology and to actually show the kids early on what they’ve got. The truth is kids actually think that technology is really cool and even back then I think the other kids thought it was really cool, but I didn’t see it that way. Kids love technology, they just eat it up, they really love it. Most of the kids that I see now with hearing aids actually seem to feel kind of proud of it. There are all these little neat things that you can put on your hearing aid, they can be different colors, or fluorescent, and they even have little things that you can attach to your hearing aids that look like earrings. So my main advice would be to just share about that stuff, just right away and not be ashamed of it, because it’s just a fact, it’s not a bad thing.

Q. Kids will be more accepting than we give them credit for?

A. Yes, much more accepting!

Q. Were you ever bullied because of your deafness.

A. I’m not 100 percent sure because I might have been—but I didn’t hear it! (Laughs). If it was coming from behind. But I really don’t think so. I grew up in a really small town (Salem, Virginia) with sweetheart kids. <ost of the kids were just really nice.

Q. This book has had amazing success, won the Eisner award. Isn’t this your first book?

Q. This book has had amazing success, won the Eisner award. Isn’t this your first book?

A. My first graphic novel, yeah.

Q. Did it win because of the message, or the drawing ?

A. Not because of the drawing. I actually think it was because the material probably seemed new to a lot of people, and I think because of the use of the speech balloon – I didn’t invent that, everyone uses speech balloons—but it worked real well for showing deafness. I think probably it was more of the speech balloon and the story itself. And the drawings are pretty good, but there are people who draw way better.

Q. Does the graphic novel format help you to reach new audiences?

A. Yes, I hear a lot from teachers and parents both, saying ‘my kid does not like to read, or has trouble reading, and this is the first actual book they read all the way through, or that they finished.’ I remember being a kid and any time a book had a more candid thing in it, that was when the book really resonated with me. ‘Oh that’s a real feeling! I know that feeling’ and I think that is what is happening with the kids. It is deeply personal but what the kids are going through is deeply personal, and they go ‘Oh yeah, I know exactly what that feeling was like.’ It sort of validates those feelings in those weird times of being a kid, and I think a lot of kids need those pictures. When you read prose and then what people are saying as in, “’I’m going to the park!’ said Barry.” For some kids all that extra stuff is confusing while having a picture of Sally talking to Barry, the kid is right there, part of the conversation.

Q. The graphic art community is a fan of yours, but what about the deaf community? What kinds of reactions are you receiving?

A. Really, really wonderful reception to the book. I was very nervous about putting it out there – and I say this in the afterword – there are so many ways that you can be deaf, there is a whole spectrum of it, and I am more on the end of deaf person who uses hearing aids, reads lips and doesn’t use sign language, and then the other end of that is deaf person, who does not want to wear a hearing aid. He uses signing, and I was worried that some people in the Deaf community, with a capital ‘D,’ would reject the book. They might say ‘this isn’t me’ but that has not been the case at all. It’s almost ‘oh, this is somebody who had similar experiences but went a different path.’ So I have spoken to many people in that community who really loved the book because it still touches on some of the stuff that we all go through together. And then on the other end, the folks who do wear hearing aids, on a path close to mine, they ate it up. “Oh this is the first time I have ever seen myself in a book!”

Q. Are you asked to speak to various groups?

A. Yes,

Q Can you sign – do you use sign language?

A. I do not sign.

Q. So you couldn’t talk to that community.

A. There would have to be an interpreter there, which always makes me feel, aggh (embarrassed), but I have been in the hearing world so long, it is not something that I felt like I needed until now, and now I am thinking, ‘you know, I’d better learn something!’

Q. Tell me about your next project.

A. Right now, I am actually illustrating books for Abrams Books (Publisher); they’re a series of early chapter books that my husband, Tom Angleberger, wrote. My husband wrote the Origami Yoda series. Those are middle grade, funny novels, but the books I am illustrating are different. These are called Inspector Flytrap, and there are totally gonzo illustrations…

Q. As an illustrator, when you are dealing with someone else’s work how do you go about imagining the scene that someone else is giving to you in verse?

A. I just try to figure out what I can actually draw. Usually when you are given the words of someone else’s work, especially if you don’t know them personally, publishers keep you in the dark a little bit because they want you to keep your own vision and not worry about what you might think the writer wants. …

Q. Do you hope to write and illustrate another book of your own?

A. Yes, I have several books coming out that are completed. I have an early reader book that also has a rabbit in it—Rabbit, Robot and Ribbit — for much younger kids. I am working on picture books and all kinds of projects. And I do hope to do another graphic novel in the future, definitely. Maybe even another El Deafo, I’m not sure.

*

Harrison is editor and Masori is a staff photographer of San Diego Jewish World. Their emails are donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com and shor.masori@sdjewishworld.com, Comments intended for publication in the space below MUST be accompanied by the letter writer’s first and last name and by his/ her city and state of residence (city and country for those outside the United States.)