By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –While I gravitated on Wednesday, April 5, to an exhibit featuring the image of Albert Einstein and another portraying the cells that I imagine Jonas Salk grappled with while developing the vaccine against polio, my grandchildren—Sky, 10, Brian, 8, and Sara, 6 – were transfixed by a room filled with toys patented in the late 1950s by the Kristiansen/ Christiansen family of Denmark.

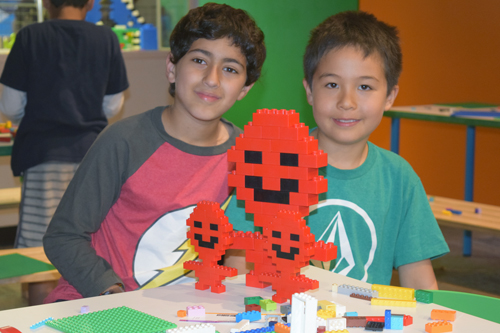

For well more than an hour, I wondered if my grandchildren would get around to exploring anything else at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center in Balboa Park, so happy were they fitting regular-sized LEGOs together on kid-sized tables or jumbo LEGOs on the floor in the “Fit-A-Brick Build Zone.”

With their grandma, and Sara’s and Brian’s mom and dad watching the children at their creative play, I visited the other exhibits and then came back to find my grandchildren still absorbed in their activity. I marveled at this because there are plenty of LEGOs at Brian’s and Sara’s house, as well as at Sky’s, so fitting the bricks together was no novelty for any of them. Yet, the LEGO’s had a near magnetic allure.

While they concentrated on what was both enjoyable and familiar, I studied a series of images taken through an electron microscope, then enhanced, that introduced viewers to the structure of viruses, how they wreak their havoc inside the human body, and how the body’s immune system try to fight them off. The large, colorized photographs, isolating these phenomena almost seemed as if they belonged in an art museum, rather than a science museum, but more and more today these disciplines seem to complement each other.

In an explanatory panel for the photograph above, written by Arthur J. Olson of the Scripps Research Institute, viewers are informed that “four different components combine to form this hollow shell of poliovirus. The four components, colored blue, yellow, red and green in this picture, assemble in a very ordered way to form the virus particle.

The storyboard continued: “The bumps on the outer surface match up with proteins on the surface of the cells the virus infects. Once drawn into the host cell, the shell opens up to release the genetic material (not shown) carried in the central cavity. The viral genes take control of the host cell, turning it into a virus-making machine. The infected host cells stop performing their normal job and symptoms appear in the infected person; the infected cells eventually die. This virus causes poliomyelitis, a rare and dangerous disease…”

Not far away, a light portrait of Einstein – created by punching holes into dark material to allow a light source to shine through – offered a lesson about perception.

If one looks at the Einstein picture up close, one cannot make out his face; all one sees is an undifferentiated series of dots. But stand back a ways, and Einstein’s face–comprised of 1200 pixels ranging from white to black with seven shades of gray in between — becomes quite evident.

The storyboard went on to explain:

“Computer monitor screens that convey vast amounts of detailed information, have anywhere from a few hundred thousand to over a million pixels, and each pixel can have 256 levels of brightness. Compare this with the information contained in the Einstein portrait made of holes; 1200 pixels, each with 9 levels of brightness. That we can recognize Einstein’s face with so little information points out how remarkable are the human powers of pattern recognition.

“How does our brain process so little information and come up, instantly, with a detailed representation of a particular face? The prevalent model is that the brain functions much like a computer that passes information simultaneously along a large number of connections among brain cells. Our brain has 10 to the 11th power cells (100 billion) and each cell has about a thousand connections to the other cells. These connections, which can have varying levels of strength, characterize the working of the brains. The simultaneous (also called parallel) style of computing of the brain is different and faster than the sequential (or serial) operation of ordinary computers.”

On reflection, my activity and those of my grandchildren were not so different. They happily focused on something they knew and enjoyed—LEGO’s—and I did the same thing, gravitating towards stories with a “Jewish angle.” Einstein and Salk were both famed Jewish scientists.

Eventually, our family migrated together to the Science Center’s IMAX Theatre where on its 76-foot wraparound screen, we watched Dream Big: Engineering Our World, in which we learned how engineers help us solve many of the problems we face in this world. For example, we saw a bridge being built over a wild river in Haiti that enabled children to go safely to the school in the next village; learned that spiraling construction on sky scrapers can increase wind resistance; and were educated about making structures earthquake resistant in the San Francisco Bay Area. Along with this, we watched as a robotics team from an Arizona high school, using only the simplest materials, was able to build an underwater robot that outperformed one assembled by students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The movie perhaps motivated the younger set of our family to explore other exhibits, including one extensive one in which visitors go from room to room to solve a Sherlock Holmes mystery. As for the oldest guy in the bunch—me – I was content following a bite to eat to sit at the outdoor tables of the Science Center’s café and watch other visitors to Balboa Park ride in vintage electric carts near the large Bea Evenson Fountain.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com