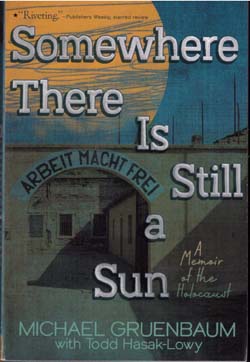

Somewhere There Is Still a Sun by Michael Gruenbaum with Todd Hasak-Lowy; Aladdin Books of Simon & Schuster Publishing; (c) 2015; ISBN 9781442-484870; 356 pages plus afterword and appendices; $8.99

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — This is a Holocaust memoir written for children of perhaps middle school age. It is narrated in present tense by a child who is 8 in 1939 and 14 when the Nazis finally are defeated. All of the narration is based on the memories of Michael Gruenbaum, who was shipped with his family from Prague to Terezin, where they were able to remain until the end of World War II.

SAN DIEGO — This is a Holocaust memoir written for children of perhaps middle school age. It is narrated in present tense by a child who is 8 in 1939 and 14 when the Nazis finally are defeated. All of the narration is based on the memories of Michael Gruenbaum, who was shipped with his family from Prague to Terezin, where they were able to remain until the end of World War II.

The actual writer of the book was Todd Hasak-Lowy, who started with Gruenbaum’s memories, researched the course of the Holocaust in Czechoslovakia, and in collaboration with Gruenbaum, masterfully narrated the combination of these two streams in the accessible voice of a youngster.

Thus, the book begins in 1939, with little Michael playing a game as he crosses a pedestrian bridge. He likes to see how many pedestrians he can overtake while running across the bridge. In other words, his life is relatively carefree.

But matters change after the Nazis take over Czechoslovakia. Soon Michael and other Jews aren’t allowed to go to parks, or to have non-Jewish employees working in their homes, or to buy certain types of desirable foods. Each week matters get worse, especially that week when two Nazi officials come to the Gruenbaum’s door and take away Michael’s father — permanently. Eventually, Michael, with his mother and sister, is forced to move to a ghetto in Prague, where to survive, they sell of most of their belongings.

Under such duress, Michael matures quickly, but there is still the child in him. One day, he removes his yellow star patch from his coat, and goes to a movie house outside the ghetto. He can’t enjoy the movie, however, so understandably paranoid is he that he will be caught. With relief, and a pounding heart, he returns to the ghetto. With Prague not much more than a prison for Michael, he actually looks forward to being relocated with his family to Terezin, where, according to the Nazis, things will be better. Michael does not know that Terezin is the “show ghetto” which the Nazis use to persuade a gullible world that Jews are being well treated under the Hitler regime.

At Terezin, Michael is assigned to a room with 40 other boys, who are supervised by a counselor (madrikh in Hebrew), who teaches them the value of teamwork, keeping clean, and caring for each other. Named Franta, this madrikh becomes a substitute father for Michael, who is nicknamed Misha. Michael is proud to be part of the team, which styles itself the Nesharim (Hebrew for eagles).

Within the boundaries of Terezin, people were allowed to go pretty much where they wanted to — the Nazis usually governing the ghetto through a Jewish council rather than directly. Soccer was a particular love of the Nesharim, and part of Michael’s life was taken up with learning ball handling techniques and defensive strategies. He also held different jobs in the ghetto — at one time working in the garden, at another time working in a bakery, where he occasionally could sneak a little extra food for himself and his mother and sister. Michael also performed in the children’s opera, Brundibar, in which two impoverished children needing to earn money for milk try to sing in the public square. However they are chased away by the mustached organ grinder, Brundibar. With the help of animals and village children, however, they are able to overcome Brundibar. Michael is surprised the Nazis don’t realize that Brundibar represents Hitler.

Juxtaposed with the more pleasant aspects of Terezin existence were times of terror, including the roll calls when the thousands of inmates would have to form lines of 100 and be counted over and over again in inclement weather. Worst of all were the transports, which took inmates “to the east,” which was the Nazis’ euphemism for the gas chambers and crematoria of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Michael was spared knowledge of what happened in “the east” until the very end of the war, when some of the survivors of Auschwitz, practically skeletons, were transported back to Terezin. Although Franta was Michael’s substitute “father,” it was his natural mother who saved Michael and his sister from the transports. Skilled as a worker in a factory where toys were made for the Nazis’ children, she and her supervisor were able to persuade the Nazi in charge of the transports that the teddy bears he was counting on as presents for his own children couldn’t possibly be finished without her.

So after a terrifying time of waiting for the transport, the Gruenbaum’s were permitted to return to the barracks. Franta, on the other hand, was transported to Auschwitz, which he survived. However, most of the Nesharim, still children, were murdered almost immediately after their arrival at Auschwitz.

The value of this book as a teaching device is manifold. It covers the progression of the Holocaust, and shows how children spiritually, if not physically, were able to resist their Nazi overlords. Franta shows the Nesharim that one stick can be broken, but that many sticks bunched together, cannot. That, he explained, is the advantage of being a team, of caring for one another, and not allowing outside forces to divide you. Under such guidance, the boys became brothers — and those who survived remained brothers long after the war. The book also teaches a few elements of soccer, providing young readers with observable truths and thereby fortifying the account of the historic Holocaust experiences.

If you are a parent wondering how to teach your child about the Holocaust, this is one book in which you can place your confidence.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com