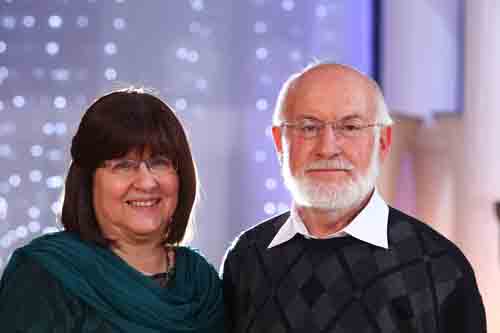

Editor’s Note: Yaakov and Toby Greenwald vividly remember what they were doing during the Six-Day War of June 1967. In these two articles, they relate their personal histories. Yaakov Greenwald is a veteran teacher of Talmud, History and Mathematics. They married in 1976, live in Efrat, and are the parents and grandparents of children spread throughout the land of Israel, from the north to the Negev. Toby Klein Greenwald is the award-winning director of Raise Your Spirits Theatre, a journalist, educator, poet and editor of WholeFamily.com.

*

I Fought 700 meters from my Home

By Yaakov Greenwald

(as told to Toby Klein Greenwald)

EFRAT, Israel — My parents had been in hiding in Slovakia during the Shoah and most of both their families died in the Shoah. In 1949 my parents got on a boat with my older brother and my younger sister and me, and we arrived in Haifa. From there we were sent to Be’er Yaakov, where we lived for six months in a “ma’abara” (transit camp) next to Rishon l’Tzion.

We arrived in Jerusalem in 1950. My parents received two rooms in an old Arab house in Ba’ka, from the government. It was a very poor neighborhood then and they were among a small group of Ashkenazi Jews who came from Hungary and Slovakia. They started their own shul and had a very close-knit community. Our home was about one mile from what was in those years the Jordanian border.

I went to school in the city center; we went alone by bus, down King David Street, and our bus was sometimes shot at by Jordanian soldiers. Sometimes the army blocked off the street due to shooting and we’d have to take a long detour. The school windows looked out at the Old City wall, so there were stones piled up on the window sills, for protection.

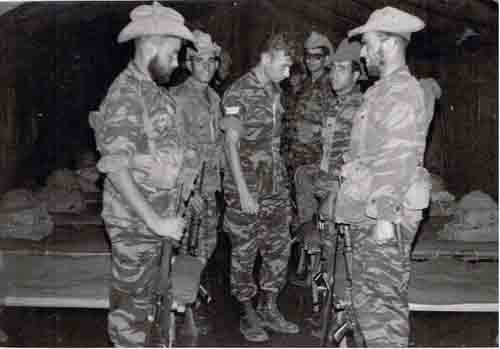

In May, 1967 I was 21, and a student in Yeshivat Mercaz Harav. Two weeks before the war, a messenger came and gave me a draft notice to go the next day to a forest near Abu Gosh (where Telz Stone stands today). There we sat in little tents that we built ourselves, and we went out occasionally for practice maneuvers in the area. I was a member of the Jerusalem Brigade, which consisted of soldiers who were all Jerusalemites. (Two years later I was transferred to the Commando unit of the Jerusalem Brigade.)

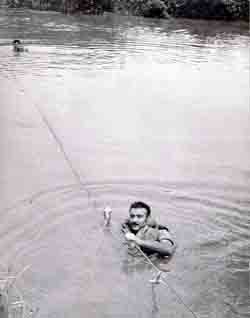

About ten days later, on a Friday, they took us up to Kibbutz Ma’ale HaHamisha, literally on the Jordanian border, and we sat in trenches that had been there since the War of Independence. We received an order from the Chief Rabbinate of the IDF to continue to dig more trenches during Shabbat. At nighttime, a small group of us would go down to the outskirts of an Arab village, Katana, to observe if there was anything going on.

On Sunday, June 4, my company was transferred to the Castel, where there was a battalion of the Tank Corps, preparing to capture the hilltops known as Sheikh Abdul Azziz; it was a post that looked down on Mevasseret Yerushalayim.

On June 5, when the Jordanians saw movements of our Tank Corps, they started shelling the Castel. It was the first time in my life that I was caught in a shelling attack; I heard the whistling of rockets above my head, and it was frightening.

At night, we moved forward to the Har Adar post, that the Arabs had tried to capture during the War of Independence. They failed, but many Palmachniks died there. Uri Ben Ari, the commander of the Tank Corp in 1967, had been among the officers who tried to capture Givat Har Adar during the War for Independence and failed. This time he succeeded.

After that, we returned to the Castel, on foot, walking for about an hour. Buses came and brought us to Yonatan Street, to the heart of the German Colony, that took us to a meeting place for the battle of Abu Tor.

On Tuesday, at 3 p.m., we began to march in the direction of Abu Tor, with the goal of capturing all of Abu Tor, from the north to the south. A company marching on nearby Hebron Street was bombarded and four soldiers were killed.

We entered the southern part of Abu Tor and an unpleasant surprise awaited us – fighting of the type that is called “in built up areas;” it is more dangerous. A Jordanian sharpshooter was hiding in one of the nearest homes, and he shot and killed four of our soldiers, each one in the head.

I was a little behind them, and I lay down with other soldiers in a long trench, and we noticed a little window in one of the houses. They asked me to shoot a burst of automatic fire into that little window, which I did. Then there was quiet. Our deputy commander, with four soldiers, approached the house from the back, and found the sharpshooter dead.

Then we continued into the heart of the village, went up to the rooftops and looked down on the village. At the same time, the platoon commander, a very well-known composer — Yankele Rotblitt, who wrote the words to to “Shir Hashalom” — lay down on one of the rooftops, and the shelling of mortars began, and it turned out that it was “friendly fire” – a shelling by our soldiers, who were sitting in the courtyard of the Ministry of Education, about two kilometers away. Their target had been the Jordanians, but there was a mistake and our platoon commander lost a leg as a result of that shelling. It is possible that the confusion stemmed from the fact that our battalion commander was killed a few minutes before that by Jordanians, in a face to face fight in a trench.

The battle ended by nightfall, and one of the soldiers was asked to watch over a house in which women and children had been gathered, and the soldier shouted to me, “The commander said you should stay here alone, to stand guard, in the village.” I was the only soldier left in Abu Tor. I stood there and watched an exchange of fire in the heavens, between the Old City and Armon Hanetziv.

When I returned to the Jordanian post that we had captured in the beginning, there were some soldiers who came to switch with us, and I heard, “Who’s there!” They thought I was a Jordanian soldier. I shouted back “Company Gimel!” When I got there, I saw four bodies on the street, the same soldiers who had been killed, from our company, and cats were approaching, so I stayed and watched over them for two hours, till they were evacuated by the army. I rode back with them to a grove of trees near the Hebrew University at Givat Ram. The whole company spent the night there.

Our company suffered heavy losses; out of our approximately 100 soldiers, nine were killed. In the entire battle of Abu Tor, 16 soldiers were killed from a battalion of about 600.

The next day, Wednesday, we got an order to capture Jordanian posts on Mount Zion, but due to our heavy losses, they didn’t send our company. Fortunately the Jordanians had fled earlier and there was no battle there. That same day the paratroopers entered the Old City through Lion’s Gate. We also entered the Old City, but through Dung Gate, and one of the company commanders, who had been born in the Old City, and was 16 years old when he was expelled in 1948, took us through the Jewish Quarter. We returned to David’s Tomb, on Mt. Zion to spend the night, and the next day, Thursday, we came back in and reached the Kotel, and saw it as it had been seen for hundreds of years.

To this day there is a historical argument over which brigade was the first one to enter the Old City – the paratroopers, or the Jerusalem Brigade, though it was the paratroopers who reached the Kotel first.

My brother, David, fought with the paratroopers in the battle of Ammunition Hill, which suffered very heavy losses, and he was wounded. He was evacuated to Sha’arei Tzedek Hospital, and our sister, Rivka, who was a student nurse, saw him brought in. At least our parents then were informed what his status was. They didn’t know what my status was until four days after the end of the war, on the eve of Shavuot, when we were released for a short vacation.

On Shavuot, tens of thousands streamed to the Kotel, which was opened to the public for the first time in 19 years. For many of them, it was their first time there, and was an experience they would remember for the rest of their lives.

**

Finals under Faraway Fire

By Toby Klein Greenwald

EFRAT, Israel — I can still remember the screaming headline in May, 1967: “Straits of Tiran Closed.” I didn’t even know where exactly Tiran was, but I knew it was bad for Israel.

It was, in fact, a blockade that Egypt put on Israel’s access to the international water of the Red Sea, and was an act of war. A variety of Arab leaders had proclaimed, over the years, that they would “throw the Jews into the sea” so which sea was academic. On May 19th, Nasser did throw the 3,500 United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) troops out of Sinai so that he could move the Egyptian army in.

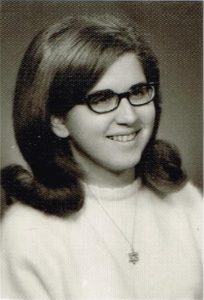

We were in the midst of preparing for and writing our 12th grade finals in Yavne, the girls’ high school of the Hebrew Academy of Cleveland, I had been active in B’nei Akiva for years, and I already had a plane ticket for July 10, to Israel, where I was to spend a year at Machon Gold, one of the few gap year study programs that existed at the time.

And then suddenly everything was thrown into question. What would happen in Israel? Today we speak about the miracles but in the dark days of May, 1967, we only knew that the situation was perilous. Every day we said extra Tehillim during Shacharit, and when our class attended a Bais Yaakov convention in Montreal that year, I remember one of the Yavne Seminary students, who accompanied us, speaking with me about attending the seminary if going to Israel would not be an option. I could not fathom the possibility, but was suddenly thrown back into the dilemma of university in Cleveland, or seminary, or…what? How could I not fulfill my dream going back years, of spending my first year after high school in Jerusalem?

Our Jewish Studies teachers were the rebbetzins of Telz Yeshiva in Lithuania, and having lost most of their families in the Shoah, and having escaped, themselves, via Shanghai, the atmosphere was highly charged. We were still close enough to the Holocaust to know that another one was a real possibility, especially on the backdrop of the violent Arab screams for death to the Jews.

There are two especially vivid images that live in my memory from those days. One is of an Israeli girl in our school, wandering the halls in distress and tears and saying that she had heard that Tel Aviv and Haifa – both cities in which she had relatives — had been bombed to smithereens. These were the only messages getting through – disinformation from the Arab radio stations. Israel (in those days before cellphones and social media) kept a tight clampdown on any information. I heard the same story later, from Israelis, who only on Wednesday began to hear the truth, when Jerusalem was liberated.

The other image is one of unity. The Cleveland Jewish community had decided to hold a mass prayer rally (I don’t remember if it was for the entire community or only for all the schoolchildren in the community), and the largest area they could find among the community properties was the parking lot of the Conservative Park Synagogue. So our school – strictly Orthodox and with what today would be called a “haredi” staff for the Jewish studies – loaded us up on buses and we joined the rest of the Jewish community – Orthodox, Conservative, Reform and unaffiliated – in that parking lot to rally and to pray together for peace in Israel.

And then the good news came. “The Temple Mount is in our hands!” The Golan, the Sinai, Judea and Samaria, with our most sacred places of the Tomb of the Patriarchs, Tombs of Rachel and of Joseph. As a member of B’nei Akiva, I was familiar with the heroic story of Gush Etzion, and that was also back in our hands now. There was great joy and relief in the community.

But nothing prepared me for the euphoria in the air when I alighted from that small El Al plane (the larger ones were still in army service) on the tarmac of Lod (today Ben Gurion) Airport on July 11, 1967. The elation of the people, and the sun, the blazing, hot, unshelled sun. I remember thinking about how Avraham Avinu sat at his tent entrance ready to welcome guests, and I finally understood the significance of it, under that hot Israeli sun. Never had I felt sun like that.

And the first words on the lips of every person and service provider we met, “Welcome home.”

A friend who had made the trip with me, and I, expected to be met by someone from Machon Gold, or from the Jewish Agency, but nobody came. Fortunately, her Hebrew was better than mine, and we managed to get our two suitcases each (plus hand luggage, books and winter coats over our arms, in that sun) onto the bus to Jerusalem.

I looked hungrily out the window on the long, winding road (before the Latrun road was renovated and shortened the trip from Tel Aviv), the same road on which medical and army convoys had been attacked during the War of Independence, and wondered when I would see the Kotel. I looked at every stone wall along the way, thinking, “Maybe that’s the Kotel?” Yes, I knew the Kotel was in Jerusalem, but my knowledge of geography left something to be desired and I didn’t know at what point we would actually enter Jerusalem, or were we already there? So my friend kindly informed me that no, we were not in Jerusalem yet.

When we did get there, and get our gear off the bus (still in the hot sun), we found ourselves in front of a bus station as small as a western stage coach station, except there were buses there instead of horses and stage coaches. We kept looking for a cab, that we had been told was a “sherut” so we naturally assumed that the plural was “sherutim” (Hebrew for “bathrooms,” we eventually discovered), and asked for that, but after several long hauls of all our luggage back and forth to the little outhouse behind the station, and seeing no cabs, we gave up and took another bus.

We were left off only two stops later, to finally walk into the cool, tall, old Arab building that was Machon Gold (we were told previously had belonged to a sheikh and all our dorm rooms had belonged to his harem) and there met the madrich who looked up at our sweaty selves and said, “Ah, we were expecting you tomorrow.”

But this inauspicious beginning was followed, for me, by a year of exploring and travel – in my free time I would get on any city bus line, ride to the end, and get off and walk around till I found another bus – and a year of learning from the greatest teachers in Jewish education – Nechama Leibowitz, Rav Yeshayahu Hadara (who that same year founded Yeshivat HaKotel), Dr. Gabi Cohn, Dr. Ephrat Piltz Ben-Menahem – teachers of phenomenal erudition, brilliance, genius.

Machon Gold was gender-wise and internationally mixed in those days, and we met students from Europe, Australia, South America, India, Mexico, and everywhere else on the globe where Jews lived and wanted to send their young people away to get a better education in the land of our forefathers and foremothers.

The education I received from my fellow students on their challenges in their home countries, their way of life, their customs, and their dreams for the future, added immeasurably to the tapestry of my education that year.

My first week in Israel I walked around the neighborhood, got to know the alleyways, tried (unsuccessfully) to find the Kotel on my own, joined a friend in a visit to Hebron — which still had white diapers and tablecloths flying from the rooftops, a sign of surrender, as they had been expecting the Israeli army to come in and massacre them, as they had massacred the Jews in 1929. We traveled by hitchhiking, which was safe in those days. One of the soldiers who gave us a ride, hearing I was from Cleveland, asked if I knew his cousin. I thought, sure, what are the chances? It turned out she had been in the group I led in B’nei Akiva, so it was my first meeting with the “small Jewish world.”

Another soldier took us up to the Ma’arat Hamachpela and showed us the notorious seventh step which was the highest one that that Muslim Mamelukes had initiated, as the closest the Jews could ascend to, which was later even more restricted, and only ended with the liberation of the Cave in June, 1967.

Exploring back in Jerusalem, I learned the difference between two Hebrew words I kept getting mixed up: “yashar” (straight) and “yemin” (right), which had me sometimes going around in circles.

I finally did find the Kotel, with a little help from my friends. Three Australian students at the Machon took me there on my first Shabbat. There were still huge boulders where the rocks of the dividing wall between the two halves of Jerusalem had been torn down, and we had to climb over those most of the way to Jaffa Gate. When we finally reached the Kotel, on that hot July afternoon, I began to cry on the shoulder of Shifra, one of Australians. “Don’t cry on me,” she said, “that’s what the Kotel is for. Cry there.”

And that Saturday night – from the sacred to the profane — she and her friends continued my education by inviting me to see an Israeli film with them, “The Policeman Azulai.” The Israeli way of watching films in those days included shouting back to the screen, clapping at the high points, eating sunflower seeds and rolling soft drink bottles down the aisles. A true community experience.

Later that year I almost left Machon Gold to join Kfar Etzion, the renewed settlement in the Gush, but I consulted with Nechama Leibowitz, who advised me, “Get your teaching degree first.” I stayed, and then began to visit the renewed Jewish community in Hevron, after their first Pesach there, where I spent many inspiring Shabbatot and vacations, where I was given the job of the first madricha of B’nei Akiva, Hevron chapter.

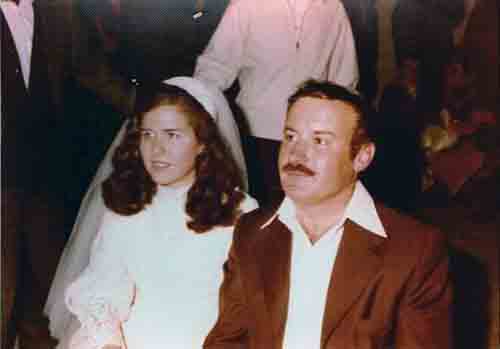

I remained in Israel, and after studying at Jerusalem College for Women, and Hebrew University, I married Yaakov Greenwald, an Israeli who had fought to liberate the Old City of Jerusalem while I was writing my high school finals.

Our family moved to Efrat, in Gush Etzion, 17 years after I dreamed of it. We have lived here since 1985, in a community filled with activism, joy and chesed.

Home.

Adapted and expanded from my article Finals Under Faraway Fire, which appeared in the March, 2017 issue of Jewish Action, the magazine of the Orthodox Union.