Editor’s Note: Editor Donald H. Harrison and his grandson Shor recently completed a 2,000 mile journey through California and Nevada, collecting and photographing Jewish stories along the way. This article is the fifth in a series generated during that trip.

Story by Donald H. Harrison; photos by Shor M. Masori

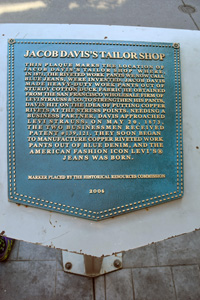

RENO, Nevada — Instead of around a water cooler, we started our conversation about ol’ Jacob W. Davis while standing alongside a plaque bearing his name at 211 N. Virginia Street in downtown Reno. Robert Wexler, a lover of history, was instrumental in persuading local civic leaders to put up the 2006 plaque commemorating the accomplishments of J.W., as he was known. Kathleen Paini Clemence, a genealogist, was able, through solid research, to tell us all about how J.W. and his wife Annie happened to come to Reno in the first place and why he had to seek the help of Levi Strauss to get a patent on his famous invention.

So we began our conversation at the plaque, but truth be told, it was just too hot over the July 4th weekend to stand there for very long, so we moved our conversation to Millies24, a coffee shop in the El Dorado Casino nearby. Amazing how air conditioning and iced tea on a too warm day can get the conversation flowing.

In case the letters get worn down, or some naughty birds so disrespect the plaque that it can’t be easily read, here is what it says:

This plaque marks the location of Jacob Davis’s tailor shop where in 1871, the riveted work pants we now call blue jeans, were invented. Jacob Davis made heavy-duty work pants out of sturdy cotton duck fabric he obtained from the San Francisco wholesale firm of Levi Strauss & Co. To strengthen his pants Davis hit on the idea of putting copper rivets at the stress points. Needing a business partner, Davis approached Levi Strauss. On May 20, 1873, the two businessmen received patent #139,121. They soon began to manufacture copper riveted work pants out of blue denim, and the American fashion icon Levi’s jeans was born. Marker placed by the Historical Resources Commission. 2006

As the story goes the wife of a rather portly fellow was tired of her husband continuing to tear his pants, and so she asked Davis if he could come up with something stronger than the usual work pants. Having made tents and horse blankets, among other durable goods, Davis decided to strengthen the pants with rivets at the pockets and at the bottom of the button fly. He sold the first pair for $3, and before long had fulfilled orders for 200 pair of these pants, then known as “waist overalls.” Realizing that he was on to something good, he wrote to Levi Strauss, who then owned a large wholesale business in San Francisco, and asked him if he’d like to partner with him. When Strauss agreed, both men’s lives were changed. The riveted waist overalls invented by Davis eventually would become Levi’s blue jeans, worn the world over.

As the story goes the wife of a rather portly fellow was tired of her husband continuing to tear his pants, and so she asked Davis if he could come up with something stronger than the usual work pants. Having made tents and horse blankets, among other durable goods, Davis decided to strengthen the pants with rivets at the pockets and at the bottom of the button fly. He sold the first pair for $3, and before long had fulfilled orders for 200 pair of these pants, then known as “waist overalls.” Realizing that he was on to something good, he wrote to Levi Strauss, who then owned a large wholesale business in San Francisco, and asked him if he’d like to partner with him. When Strauss agreed, both men’s lives were changed. The riveted waist overalls invented by Davis eventually would become Levi’s blue jeans, worn the world over.

The plaque celebrating how this outdoor work clothing started in Reno was unique in several ways. Most notably, it is in the shape of the back pocket of a pair of blue jeans. And in the top corners of the pocket you can see a material representing the rivets. Although the story board was written by Mella Harmon of the Reno Historical Resources Commission, Wexler had considerable input. Please, he pleaded with the historian, don’t use too many dates because “dates are way overused in plaques and markers, leaving out even more interesting and important elements.” Additionally, he urged that the narrative be “reader-friendly,” explaining that in his travels around the world, he likes to read plaques and too often, “the writers of plaques and markers squeeze the enjoyment of history out of them and they become bland and dry like encyclopedia entries. An historical plaque should serve as a tiny book!”

Of course, there is a whole lot more to the story than a plaque can tell, and here is where genealogist Kathleen Paini Clemence comes in. She didn’t initially set out to learn about Jacob W. Davis, but that’s where her research led her. Gertrude Marion Packscher was her mother’s cousin. “I knew all about Gertrude’s mother’s family because that’s my mother’s side, but I didn’t know anything about her father’s side of the family.” So, she started researching the Packscher family, in the process collaborating with Deb Freedman of Tacoma, and Nancy Arndt Finken, a great-granddaughter of J.W. and Annie Davis. Along the way, Clemence discovered that Annie Davis’s maiden name was Annie Packscher, and that she was a cousin of Gertrude’s grandfather, Adolph Packscher. Now, the story of the Reno inventor had come close to home.

Her research was benefited by two court cases in which J.W. Davis gave depositions about his life, Strauss vs. Elfelt and Strauss vs. King, records of which she found in the national archives. Davis was born in 1831 in present-day Latvia in a town near Riga, his original name being Jacob Youphes, according to the genealogist. He arrived in New York City by ship in March 1854, according to his testimony, and worked first in New York City and later in Maine as a tailor. In 1856, he decided to take a steamer down to the Isthmus of Panama and cross by train from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean, where he caught another steamer that took him to San Francisco. After working briefly there, he traveled to Weaverville in California’s Trinity County, and in 1858 went north to the Fraser River of British Columbia where he sold dry goods to miners. He traveled inland to the Cariboo region of British Columbia, eventually winding up in Williams Creek, from which he temporarily departed for Victoria, according to his deposition, “the principal business for coming down there was to get married.”

To date, Clemence has found nothing to indicate how J.W. and Annie came to know each other, leading her to suspect that perhaps Annie was a mail order bride – one of many women who came to the rugged Canadian mining country to be married. She noted that Seraphina, Annie’s sister, married Isaac Pincus, who was a business partner with the sisters’ cousin Adolph Packscher, and that Annie and J.W. Davis were married by the same rabbi just nine days later – so perhaps a shidduch had been arranged by Victoria’s tiny Jewish community.

Davis soon took his bride back to the Cariboo where she subsequently gave birth to their first child, reportedly the first non-native child born in that area. The couple tried partnering in a brewery with Frederick Hertlein, but that proving unsuccessful, they returned to Victoria in time for her to give birth to their second child. Later on they went to San Francisco, where J.W. pursued an unsuccessful venture in the coal business. Perhaps because of his huge financial losses, he went with Annie to Virginia City, Nevada, where Annie’s older brother, Simon, operated a cigar store in the International Hotel, then one of Nevada’s finest. J.W. worked for his brother-in-law only a short time before he moved around the corner to open a tailor shop, his fallback occupation. The Davises stayed in Virginia City only a year, and then moved to Reno, which though far smaller than Virginia City, was about to become an important railroad town. “He came on the 8th of May of 1868 and Reno was founded as a town on May 9th. ” The railroad chose to name the town after Maj. Gen. Jesse W. Reno, who had fought for the Union during the Civil War.

Davis’s first job in Reno was in a brewery with Frederick Hertlein, with whom he previously had partnered in the Cariboo. But history repeated itself. The brewery could not support two families, and so Davis moved around the corner to Virginia Street to establish his tailor shop.

Before Davis wrote to Strauss for help in obtaining the patent, according to Clemence, Annie who was then the mother of five children under the age of 7, put her foot down. Davis had been spending all of his available time as a tinkerer, an inventor, and each time he applied for a patent it cost him $68, a lot of money then, perhaps equivalent to $1,300 in today’s money. One of his patents was for an improvement in ironing and stretching boards; another, taken out in Annie’s name, was for an improvement in wardrobe closets.

By the time that J.W. developed the riveted pants, according to his testimony, “I have spent so much of my time and all of my earnings on all those various experiments and inventions. My wife was crying and begged me not to spend another dollar in inventions because we needed every dollar that I earned.”

Many people have the impression that Levi Strauss was the original supplier of duck and denim materials to J.W. Davis, but Clemence said her research indicates otherwise.

She said he wrote to his brother in law Simon Packscher, saying he needed some good duck material. Simon, while in San Francisco, contacted his cousin Adolph, who was then a successful dry goods merchant. Adolph recommended Levi Strauss, who was a wholesaler in dry goods. Simon and Adolph met with Levi Strauss to purchase the materials, and J.W. subsequently reimbursed his brother-in-law. At that point, according to Clemence, J.W. became aware “that Strauss is an honorable man, so he writes to him, if you put up the $68, I will give you half the patent rights and oh, by the way, if you do this, I am willing to go to San Francisco or New York to oversee the manufacturing.”

Clemence said Strauss and Davis exchanged correspondence via Wells Fargo stagecoach, and reworked their patent application several time. “As soon as the patent is approved on May 20 Davis goes to work at Levi Strauss & Co. and works there until the days he dies, as the plant manager, essentially.”

Initially, she said, the waist overalls continued to be made from white cotton duck, but denim became the fabric of choice in 1874.

Annie and J.W. had eight children in all, although two of them died in infancy. Simon, who succeeded his father as plant manager at Levi Strauss & Co., invented a children’s playsuit called Koveralls, according to Clemence. This was the first product Levi Strauss & Co. marketed nationwide; at the time jeans were distributed solely on the west coast, she said.

Clemence speculated that if Annie hadn’t put her foot down about not risking another $68 for the patent, the pants we call Levi’s might never have become the iconic brand they are today. In San Francisco, Tracey Panek, the historian for Levi Strauss & Co. told me that while Davis’s contributions as an inventor were important, he didn’t have the marketing savvy or resources that Levi Strauss had to turn the riveted waist pants into a well known brand.

I wondered whether Davis ever resented the fact that his invention came to be called “Levi’s” rather than “J.W.’s” or some other play on his name. Historian Panek told me that during both men’s lifetimes, the pants were sold as waist overalls, and later as 501s, named for a lot number. Levi’s was a name that was adopted much more recently, she said.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com