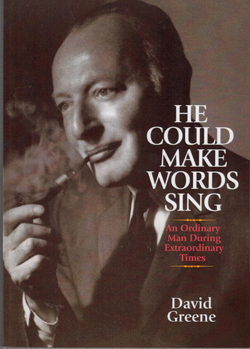

He Could Make Words Sing: An Ordinary Man During Extraordinary Times by David Greene, © 2017 DCG Publishing; ISBN 980998-018201; 193 pages plus endnotes; $17.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – History teacher David Greene has written a combination social history and biography of his father-in-law, Harry Greissman, an advertising man.

SAN DIEGO – History teacher David Greene has written a combination social history and biography of his father-in-law, Harry Greissman, an advertising man.

We come to know Greissman as a child of immigrant parents who scrimped and saved so that Harry could go to college. He later went off to World War II, thinking he’d remain an enlisted man, but was made into an officer who could teach others the vagaries of artillery targeting. He fought in Germany, and because of his facility with languages, stayed after the war to assist in the research necessary to prosecute Nazi war criminals.

After coming home, he joined the advertising profession—a trade in which he would advance to the security of middle ranks, but never to the top, as the pinnacle of the profession, then, was guarded jealously by Gentiles. Harry nevertheless was happy. He moved with his wife Iris from Brooklyn to the Westchester suburbs, where they raised three children—the youngest, Allan, a surprise, who came ten years after the second child.

As the book title suggests, Harry had a way with words, and he could use them effectively not only for his advertising agency, but in helping a Westchester county politician rise to town office, and in aiding daughter Jamie (whom author Greene married) to submit the best idea for naming a school project.

Harry’s memories of the Depression made him tight with money, but Iris often got around his frugality. His true love was tennis, and the heirs who played it with him, felt a strong sense of camaraderie. But, at other times, he was reserved, unlikely to say “I love you” out loud, and when he played tennis with others, his children sometimes would feel jealous of his time.

World War II must have had an impact on him, but it was not something he would readily talk about. Clearly, he had felt a sense of duty to his country, and was dismayed when his children’s generation did not respond during the Vietnam War to their nation’s call to arms with the same sense of patriotism. Perhaps the fact that his oldest son, Richard, had a fairly high draft number secretly relieved him. Who wants a son to go off to war?

We can sense the impact on Harry of these two cataclysmic events—the Great Depression and World War II – but afterwards, as the 50’s Cold War, 60’s protests and assassinations, 70’s Watergate scandal and OPEC-spawned price inflation; 80’s Reaganomics; and 90’s Dismantling of the Soviet bloc, pass by, it is harder to see the nexus between these events and Harry’s life. Harry read about all of them in the newspaper, preferably on a porch, while smoking his beloved pipe, but did they really impact his life?

Greene doesn’t attempt to prove any connection; these events go by like a newsreel at the movies. Something to watch, and maybe consider, before the main feature.

I dare say that without Greene’s tender recollection of his wife’s father, few people outside of his family and circle of friends would today have heard of Harry or noted that he passed away at age 82 on December 18, 1997. Greene has left us far more than a family memoir—although He Could Make Words Sing certainly is a superlative example of that genre.

What Greene does in this book is to prompt us to remember some of the events in our parents’ lives, and our own, with some nostalgia; to reflect on the comparisons between the generations of Harry’s family, and our own; and to wonder how our parents’ lives, our own, our children’s, and our grandchildren’s have been influenced by international events, domestic social movements, and changes in the economy.

Isn’t that the role of a teacher after all? To help us crystallize relevant questions, and to provide us with the tools to seek their answers?

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com