Editor’s Note: This is the 16th in a series of stories researched during Don and Nancy Harrison’s 50th Wedding Anniversary cruise from Sydney, Australia, to San Diego. Previous installments of the series, which runs every Thursday, may be found by tapping the number of the installment: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

By Donald H. Harrison

WELLINGTON, New Zealand – Rabbi Solomon Katz died in 1944, a year before I was born, but I feel I owe him a debt of gratitude for being so ready to accept the call to become spiritual leader of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation in 1931. In a way, it’s all thanks to him that Nancy and I had such wonderful visits here, as well as in Sydney, Australia, and later in Auckland, New Zealand.

Wellington’s Jewish community had been emotionally devastated by the death in 1930 of Rabbi Herman Van Stavaren, who had led the congregation for over 50 years, and then was stunned again when Van Stavaren’s long-time assistant minister, Rev. Chananiah Pitkowsky, a much younger man, died a month later. For a year, the late Rabbi Van Stavaren’s two sons served as lay readers while a committee searched for a suitable pair of spiritual leaders, it being the custom in the congregation to have a senior minister and an assistant minister. (Rabbis in New Zealand at the time were described as “ministers,” and called “Reverend.” They also wore clerical collars.)

When the call came for a senior minister, Rabbi Katz had been serving Congregation Ansche Sholom in New Rochelle, New York, where my mother, then known as Alice Levine, was best friends with the rabbi’s daughter, Dorothy Katz. Mom’s father, Samuel Levine, taught Hebrew school at Ansche Sholom. So, while the rabbi and my grandfather were colleagues; my mom and the rabbi’s daughter were schoolmates and confidantes. Although New Zealand was far away, Rabbi Katz was already quite familiar with the country. He had served as an assistant rabbi in Auckland, New Zealand. The two cities are both located on New Zealand’s North Island, Auckland near the top; Wellington at the bottom, across the Cook Strait from South Island. Wellington is the nation’s capital; Auckland, a larger city, is the seat of its business. The two cities’ relationship is equivalent to the one between Washington D.C. and New York City.

I remembered the friendship that my mother and Dorothy had maintained through their marriages; Dorothy’s to Sid Moses, and mom’s to my father Martin B. Harrison, and some years after dad’s death, to her second husband, Harry Walters. Not only did mom and Dorothy correspond often, but Dorothy, who was a journalist, and Sid, who headed a large furniture concern, traveled on business periodically to the United States, making it a point to stop in New Rochelle and later in Encino, California, to visit with my parents. Some of the Moses’ family friends followed in their footsteps, so as a boy, I was used to hearing New Zealand accents at the dinner table. I also developed a pretty good collection of cancelled New Zealand postage stamps.

Although my parents and Dorothy and Sid all are dead, I decided to try to track down Dorothy’s and Sid’s children, if possible, in order to visit with them. I contacted the New Zealand Jewish Federation and told of the two families’ relationships, and within a day or so, I received an email note from Barbara Moses, Dorothy’s daughter-in-law, saying that she and Dorothy’s son, Roger, would love to see Nancy and me when our ship arrived in Auckland. It was suggested in ensuing correspondence that we could also meet Roger’s sister, Miria Clements, her husband Anton, and their son Carey, while we were in Wellington. Furthermore, Roger and Miria had a cousin, Philip Moses, who lived in Sydney, Australia. As it turned out, Philip was about to visit San Diego, and so, we had the opportunity to host him and his wife, Donna, when they came to our city prior to our own trip. I’ve written about Philip and Donna in previous articles in this series, as our cruise aboard the MS Maasdam started in Sydney, and we had three enjoyable sightseeing-filled days with them.

So, it was with quite a bit of anticipation that we disembarked in Wellington, where we were met by Carey, who is Dorothy’s grandson, as well as a project archivist for Wellington High School and a sports journalist. He took us to the Wellington Jewish Community Center, which includes the synagogue, as well as to a nearby memorial to New Zealand’s war dead. Jews in New Zealand served in that country’s military in greater proportion than their percentage in the population, perhaps for the reasons voiced during World War II by Rabbi Katz on the occasion of the 100th anniversary celebration of the founding of the congregation.

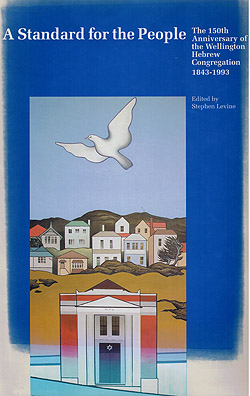

Rabbi Katz had been born in Kishinev, Russia, and migrated to London, England, to study before accepting clerical posts with increasing responsibilities in Auckland, New Zealand; and these U.S. cities: New York, Montgomery, Birmingham, and New Rochelle. As reported in A Standard for the People: The 150th Anniversary of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation, 1843-1993, Rabbi Katz appreciated the freedom he found in New Zealand, especially as contrasted to the horrors occurring in Nazi-occupied Europe, against which New Zealand was then at war. In a speech he made marking the 100th anniversary of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation, he said:

Rabbi Katz had been born in Kishinev, Russia, and migrated to London, England, to study before accepting clerical posts with increasing responsibilities in Auckland, New Zealand; and these U.S. cities: New York, Montgomery, Birmingham, and New Rochelle. As reported in A Standard for the People: The 150th Anniversary of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation, 1843-1993, Rabbi Katz appreciated the freedom he found in New Zealand, especially as contrasted to the horrors occurring in Nazi-occupied Europe, against which New Zealand was then at war. In a speech he made marking the 100th anniversary of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation, he said:

So we meet today in joyous conclave to celebrate the occasion of our centenary in worship and in thanksgiving to God, who directed the footsteps of our fathers to these blessed shores, where they found a haven of peace—a land of freedom, justice, and opportunity, where barriers of race or religion do not exist, and a person was allowed to worship God and practice the dictates of their religion according to their own conscience. And the ideals of truth, liberty, and righteousness in which our country was cradled have continued to be the guiding principles of the Government and the people of New Zealand to this day.

Turning on that January day in 1943 to the destruction befalling European Jewry, Rabbi Katz urged his congregants to “pledge ourselves before God to do all in our power to help and preserve them from utter annihilation. Every means at our disposal shall be placed at the service of the cause of our stricken brothers. We pray God that Nazi tyranny may be speedily broken and deliverance and salvation come to Israel and to the world at large.”

One can imagine the congregants sorrowful assent as Rabbi Katz bespoke the need for resoluteness in the face of “the insane ferocities that the cruel and frenzied Nazi power is inflicting upon our people.”

The Wellington Jewish Community Center is the home of a collection of buttons, 1.5 million of them, some of which are shown at its small Holocaust Museum to touring school groups, and more and more often, are taken on the road to other communities in New Zealand. The project reminded me of San Diego’s own “Butterfly Project” in which an attempt is being made to have 1.5 million ceramic butterflies painted and affixed to walls throughout the world. Both projects, memorialize the 1.5 million Jewish children murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

The book on the 150th birthday of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation—along with conversations with Miria, Anton and Carey Clements, who took us all to lunch at the botanical gardens, helped me piece together some of the story of what happened in the life of Dorothy Katz after her father, mother, two brothers, and she moved to Wellington to live at the home at 128 Terrace that was provided for the rabbi and his family. According to a remembrance Dorothy wrote in the sesquicentennial book, the home could be reached by “walking down a lane at the side of the synagogue,” which since has been replaced by the more modern complex at the Jewish Community Center. Dorothy recalled an “old-fashioned ice box, a stove in which fires had to be lit for cooking, heat from fireplaces, a gas caliphont over the bath to heat water.” And, she noted, “It took us a while to get used to Dad wearing a clerical collar; rabbis don’t wear them in the United States.”

In another section of the 467-page coffee table book, congregant Ernest Markham reminisced:

“The rabbi by this time was Solomon Katz from America. At first, he was viewed with suspicion because he wore an ordinary shirt and tie—no back to front clerical color for him. He was assisted by the Rev. Samuel Kantor who eventually settled in Tel Aviv with one of his daughters … Rabbi Katz was a scholarly man, more a teacher than theatrical celebrant, and his love of teaching bound up even the worst behaved among us sometimes to literally sit at his feet on a Sunday afternoon, listening to stories about communities in far away exotic places like India where Jews were dark skinned and otherwise indistinguishable from their Indian neighbors. I remember him with continuing affection as the man who taught me that Judaism was not a state of mind you put on for Friday nights and Saturday mornings.”

Gerald Shapiro, another congregant, wrote:

“My early recollections of the Jewish community are of going to Hebrew School and of Rabbi Katz, Dorothy Moses’s father. I felt that Rabbi Katz took a very keen interest in me, and not only in my religious education but in my secular education as well. I can remember sitting with him at a … bar mitzvah, being advised to go to university, to get an arts degree, to educate myself and then to study law. I was still at high school, at Rongotai College, and during those days we used to have midweek Hebrew classes. Rabbi Katz used to come to Rongotai College because there were a lot of Jewish boys there, and we would use the headmaster’s secretary’s office (the secretary being Naomi Goldsmith, the daughter of J. I Goldsmith who later became a congregation president.)

Ellis Greenberg, too, remembered Rabbi Katz fondly, describing him as a “very, very learned man. His oratory was fabulous, his sermons tremendous, even as a boy I can remember his great ability as a speaker.”

I couldn’t help but think of my own rabbis at Tifereth Israel Synagogue in San Diego: Aaron Gold, of blessed memory, and Leonard Rosenthal, recently retired, and now Joshua Dorsch. How many, many lives they have touched through the diverse services and duties they successively and successfully performed at our Conservative congregation. The books our congregants could write about them, I marveled.

American Marines stationed in New Zealand during World War II were welcomed by the congregation, and they became particularly fond of Rabbi Katz. Reading a letter from Rabbi Myron Silverman of Cleveland, Ohio, after Rabbi Katz’s death, I could sense the Marines’ emotion at losing someone who had provided them a spiritual sanctuary so far from home. The letter accompanied a plaque that had been fashioned by members of the 2nd Marine Division “in grateful tribute to the memory of Rabbi Solomon Katz.” Rabbi Silverman wrote:

One day I arrived at the chapel at Kamuela (Hawaii) to find most of them down at heart and saddened by something I could not suspect until one of them showed me clippings from a Wellington paper telling of the death of Rabbi Katz. Their sorrow at this news was universal and profound, and I was stirred by the fact that these young men, hardened by battle, could so readily display the bereavement they personally felt. And so, without preparation, the service that afternoon became a memorial service, for they, as one, wanted to rise and recite the Kaddish in respect to his memory. Without my realizing it, there was no stir or commotion during the service, a large number of men attending it managed somehow to raise out of their pockets a sum amounting to 75 dollars—a considerable sum for a group of GIs unprepared for this spontaneous collection. Following the service, the men requested that the money be used to provide a memorial from them at the Wellington synagogue in Rabbi Katz’s memory … I know that Rabbi Katz served his God with dedication and distinction, but there is no greater praise of him and respect for him in the hearts of those men whom he lovingly served.

Hundreds of people attended Rabbi Katz’s funeral. Afterwards two of the rabbi’s four children then living in New Zealand, Alfred and Dorothy, donated his extensive collection of books to the Central Public Library, thereby forming the Rabbi Katz Memorial Library. They donated his robe to the synagogue, and it became a tradition of his successors to wear it at services.

The last entry in Rabbi Katz’s diary read: “Bar mitzvah lesson, Anton Clements.” Years later, Anton married Miria Moses, the granddaughter of Rabbi Katz.

Interestingly enough, the Clements and the Moses families had side by side businesses on Manners Street in Wellington’s business district. An article in the sesquicentennial book by Michael Clements, who is Anton’s brother as well as a former president of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation and archivist for the New Zealand Jewish Archives, explained that his father, Arthur Clements, owned the Regal Fur Company at 18 Manners Street, and that Sid Moses—who became the husband of Dorothy Katz—was managing director of Maple Furnishing Company.

“The Regal was long and narrow, with two windows on either side of the entrance door,” Michael recalled in his article. “It had rows of fur coats and stoles on both sides of the shop. Other stock was displayed on mannequins and the whole place smelled of mothballs. When my father came out of the back (where the workroom was situated), he invariably wore a white working coat with square pockets at the sides and a pen or two clipped in his top pocket. … He purchased his furs from various contacts overseas, and also from local suppliers and traveling salesmen. Dad matched the skins for colour and prepared them for sewing together by two fur machinists, Mrs. Mary and Mrs. Coxon, who were with him for over 20 years. The coat was finished off with lining, button holes and/ or hooks and eyes.”

A photo of Arthur Clements on horseback as part of the Palestine Gendarmerie in 1921 is printed in the sesquicentennial book.

The Maple Furnishing Company, according to Michael Clements, was “then one of Wellington’s best known furniture stores. ‘It’s easy to pay the Maple way’ was its motto, frequently advertised on the tram cars which rattled around town. The store had two floors and it had two entrances, one in Manners Street and the other from Willis Street. The Maple, as it was known, was founded by Claude and Harold Moses in Auckland in 1914. In 1934, Sidney Moses joined the firm in the sales department, four years later opening the Wellington branch as managing director. The Maple continued to operate until the late 1950s, when it was amalgamated with Smith and Brown Limited … “

Sid Moses’ father, Claude, had been president of the New Zealand Dental Association as well as president of the Auckland Hebrew Congregation, so in a sense the marriage of Sid Moses and Dorothy Katz represented a union of New Zealand’s two largest congregations. During Claude’s tenure as president, he successfully recruited Rabbi Alexander Astor (ne Ostroff) of Dunedin to become Auckland’s assistant rabbi—the same position Rabbi Katz once held.

The Wellington Hebrew Congregation hands out special honors for Simchat Torah celebrations. The person who gets to read the last part of the Five Books of Moses is called the Chatan Torah, while the person who immediately afterwards reads the first part of the Five Books of Moses is called the Chatan Bereishet. In 1946, Arthur Clements was selected to be the Chatan Bereishet. Thirty-eight years later, his son Michael was selected to be the Chatan Torah.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Judith Boock who loaned me the sesquicentennial book so that I might better understand what life had been like for Dorothy Katz and her clan since she and my mother said “goodbye and write soon” on that long ago day in New Rochelle, New York.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Pingback: Name changes helped kiwifruit growers, architect | San Diego Jewish World

Pingback: John McCormick: A Kiwi friend of Israel | San Diego Jewish World