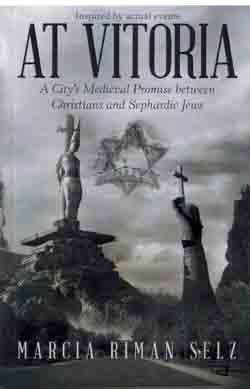

At Vitoria: a City’s Medieval Promise between Christians and Sephardic Jews by Marcia Riman Selz;© 2016, Archway Publishing; ISBN 9781480-852976; 217 pages plus appendices, $17.99.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – While the Basque people of Vitoria, Spain, were Christians, like the Jews, they were outsiders, not quite like the other Christians of Castile or other parts of newly united Spain. So, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella began issuing edicts against the Jews, the Basques were never particularly quick to enforce them. Besides, when illnesses had swept the region, their own Christian doctors had fled, but the Jewish doctors remained behind, saving many Basque families. This special bond could never be forgotten.

SAN DIEGO – While the Basque people of Vitoria, Spain, were Christians, like the Jews, they were outsiders, not quite like the other Christians of Castile or other parts of newly united Spain. So, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella began issuing edicts against the Jews, the Basques were never particularly quick to enforce them. Besides, when illnesses had swept the region, their own Christian doctors had fled, but the Jewish doctors remained behind, saving many Basque families. This special bond could never be forgotten.

In Marcia Riman Selz’s historical novel, events unfold through the eyes of the Crevago family, whose members are shoemakers, doctors, and scholars. The Crevago brother who delivers elegant shoes to customers throughout Spain has the misfortune to witness a treasured friend and his wife burned at the stake for continuing to practice their Jewish religion after pretending to convert to Catholicism. It was a sight he never could forget, but nevertheless he could not persuade other members of his family to pull up stakes and leave Spain for safer countries, perhaps Holland. Those who have read Holocaust literature will be familiar with arguments made by this family in an even earlier era of hatred for remaining in a town where they had enjoyed business success and social ties. Add to those reasons the amity between the Basque and Jewish communities, and the Jews of Vitoria decided to stay put – at least while the choice was theirs.

Among the Basques, as with all peoples, there was a criminal element. The novel details two brutal instances of sexual violence perpetrated against female and male Crevago family members. Life in Vitoria, was by no means perfect, but compared to the scourge of religious hatred elsewhere in Spain, the risks seemed acceptable.

Eventually, however, Ferdinand and Isabella, at the urging of the Catholic Church and Torquemada, its Grand Inquisitor, ordered all Jews to convert, or die, or vacate every inch of Spanish soil. Against this edict even the Basques were powerless to intervene, and so the Jews of Vitoria had to pull up stakes and leave, but to where? Anyone who ever has seen the play or movie, Fiddler on the Roof, cannot help but be reminded of the Jews asking the same questions before they began pushing their carts loaded with their belongings from the mythical Russian empire town of Anatevka.

At Vitoria opens in Bayonne, France, which lies on the other side of the Pyrenees from Spain. It is here where most of the Crevago family settled because it too is a Basque town. The question before the Jewish community in Bayonne was whether to release the development-minded Basques of Vitoria from a pledge made in 1492, the year of the Expulsion, to maintain the Jewish cemetery. The question is controversial, not only for the Jews, who want to remember their past, but also for some Basques, who want to continue honoring the centuries-old pact.

I mentioned that besides doctors and shoemakers, the Crevago family had its scholars. One in particular decided to convert to Catholicism so that he could learn more about the world. In this fictional version of history, he changed his name to Luis de Torres and sailed west with Christopher Columbus.

While I am glad that I read this novel, and would recommend it to others, I have mixed feelings about it. I believe both the Holocaust and Fiddler on the Roof were likely 20th Century influences on author Selz’s telling of this 15th Century story, giving me—and possibly other readers—a sense of “seen that, read that.” Likewise, I felt that some of the Jewish prayers uttered by characters in this story were taken from modern siddurim, possibly Ashkenazic rather than Sephardic.

Moreover, there are many legends about Luis de Torres, who as Columbus’ translator was expecting to reach the Asian continent. According to one legend, he tried communicating unsuccessfully with the indigenous people of the Caribbean in Hebrew and in Arabic on the theory that they might have been descended from the Ten Lost Tribes. I have misgivings about Selz making the historical Torres a member of the fictional Crevago family, because this flight of imagination may, in time, find its way into the historical record, which I believe should remain sacrosanct. On the other hand, I liked the way Selz brought a woman’s voice to this era of world history, reflecting as she did upon the limited choices women faced in an era when they were neither permitted education nor given choices in whom they might marry. Nevertheless, they often held sway over domestic matters. Selz’s depiction of the home lives of the extended Crevago family are so evocative, at times I felt I was sitting down with the family at the main meal.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com