By Lazar Wall

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil — Freddy was five when he saw a paving stone shatter his dad’s storefront in Berlin. Next, also in front of the family, the Nazis beat up his father.

Adolf Hitler had made life unbearable to the Glatts already in 1933, forcing them to scramble to Antwerp.

In the new city Freddy was enrolled in a public school and joined the Zionist youth movement Maccabi Hatzair. The German-speaking boy learned Flemish, Hebrew, Yiddish, and French. Anti-Semitism existed there too and the kids were often sworn at, spat on, and beaten.

When the first air raid struck Antwerp in 1940, Belgium no longer felt protected from the war. The advance of Nazi Germany called for a new getaway and grandpa Salomon booked four spots in the back of a dump truck to the French border. To young Freddy, the thousands of refugees along the way looked like the Hebrews fleeing Egypt. His two teenage brothers were to bicycle their way to the border.

Shortly after crossing into France, the family boarded a train that was later targeted by two German Stuka airplanes. The attack sent shrapnel to Freddy’s leg, which took months to heal. The family settled near Toulouse in Vichy France, but the two teenagers never showed up. By that time, Freddy’s parents were divorced and his father had moved to Brazil.

Information was only available from incoming refugees and a newly arrived acquaintance said the teenagers had missed the last boat from Dunkirk, France to Dover, England. So they drove an abandoned car back to Belgium, moved to their family’s home and reopened grandpa’s store. Ecstatic at the news, grandpa Salomon longed to depart. The family would be reunited and his life savings, hopefully still hidden in Antwerp, would whisk them out of Nazi Europe.

They traversed Nazi-occupied France initially in a Belgian-built Minerva limousine with the help of a people smuggler, then on foot and by train. And the whole family got together in Antwerp. Grandpa Salomon, whose savings were intact, started running his business again. But soon wearing a yellow Star of David badge on the clothing would be mandatory for them.

A year later the Jews of Antwerp were ordered to move to the Heusden village, near the border with Germany and Holland. At 13 years old Freddy couldn’t have his Bar Mitzvah. This concentration camp was dissolved some seven months later, as Germany was too busy transporting millions of Jews from Eastern Europe to their deaths.

The Glatts were allowed back to Antwerp except for the older boys, Bubbi and Heinz, who were sent to a coal mine. In 1942 both were summoned to work on the Atlantic Wall, a fortification meant to contain an expected Allied advance. Once on the train, they were instead taken to Auschwitz.

Meanwhile the Gestapo, helped by local spies such as the Flemish Hitler Youth, actively hunted the Jews who remained in Belgium. Freddy’s grandparents Salomon and Chawa were found and deported to Auschwitz.

Decades later Freddy learned that Salomon, Chawa, Bubbi, and Heinz were murdered in Auschwitz in 1942.

In a new effort to hide from the Nazis, Freddy and his mom moved again, now to a small apartment at 101 Jerusalem Street in Brussels’ Schaerbeek district. The bathroom was tiny, meaning Freddy had to use a public shower, carefully hiding his circumcision.

At the age of 14 he started working as an assistant to a newsstand owner delivering L’Avenir, Het Laatste Nieuws, and Le Soir. At night he worked in a clandestine battery factory, and in between shifts Freddy would draw Mickey Mouse-themed cards for sale at a stationery store. He would also steal train tracks and sell them as scrap.

The money afforded him and his mom rare visits to the movie theater. The films were always preceded by newsreels depicting Luftwaffe bombs raining down on London and Operation Barbarossa crushing the Soviet Union. Also, he often sneaked into the Palais des Sports arena to watch wrestling, boxing, and other sports events.

As the war went on, persecution and scarcity worsened, and Freddy’s mom Rozalia asked the Chief Rabbi of Belgium to find her son a safe place. With support from the Belgian and Jewish resistances, and from Queen Elisabeth of Bavaria, Freddy set out for a seminar for Catholic boys.

While getting used to the new rites, from the playground he could see hundreds of American B-17 bombers headed for Germany. Maimed Nazis, repelled by American and British soldiers just in from Normandy, were another omen.

When the Allies finally liberated Belgium, Freddy reunited with his mom and both started to frantically look for the missing relatives, still unaware of their fate.

In 1947 mother and son moved to Brazil. Freddy’s dad was no longer addicted to card games, the trigger for divorce, and the couple remarried in Rio de Janeiro.

*

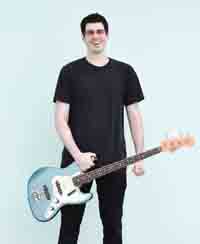

Wall is the founder of the rock band One Man Mambo. His son ‘101 Jerusalem’ is based on the real-life story of Freddy Siegfried Glatt.

Fiquei emocionado ao ouvir tua musica. Muito obrigado Luiz…