By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO –In some cases, sculptures are grouped to tell a story, but at other times their storytelling groupings are accidental. You’ll find both sets of circumstances outside the San Diego Museum of Art.

For example, two Jewish artists who immigrated to the United States from the Czarist Russian Empire have sculptures located close together where the museum’s outdoor café melds into the Sculpture Garden. “Night Presence II,” a large outdoor sculpture in welded cor-ten steel by Louis Nevelson (1899-1988) is within a short distance of the copper relief “Sonata Primitive” by Saul L. Baizerman (1889-1957).

Nevelson moved as a child in 1905 from modern day Ukraine to Maine, where her father established a lumber business, and from which she later escaped to New York City as her artistic abilities blossomed. Baizerman had grown up in Vitebsk, Belarus, a city made famous by his fellow artist Marc Chagall. Opposing the czar’s government resulted in Baizerman being sent to prison, and after he got out, he migrated in 1910 to New York. He was then 22.

If “Night Presence II” looks to some like it was carved from a dark wood, that may have been the influence of Nevelson growing up the daughter of a lumberman. Some critics said Nevelson’s sculptures are too masculine, but Nevelson dismissed the criticism, saying that art transcends gender.

Baizerman, reacting to oppression by the Russian czars, dreamed of a worker’s society in which class distinctions would be erased. Leading me and my neighbor Bob Lauritzen on a tour of the outdoor sculptures, Anita Feldman, the museum’s deputy director for curatorial affairs and education, commented about Baizerman’s copper relief sculpture, featuring the torsos and heads of two figures. “Notice that it is all hammered by hand; it is very labor intensive. … For him, it is very important to show the physical, manual effort that goes into making a sculpture, and yet he creates something that is very poetic. He has these two figures together, sort of romantically entwined, especially as it’s a relief, so there is air all around it.”

As we stepped from the outdoor café to the Sculpture Garden, we saw a piece by Alexander Liberman (1912-1999), called “Aim I.” Like Baizerman and Nevelson, Liberman was born in the Russian Empire, but his Jewish family was given permission by the Leninist government in 1921 to move to London. As a school boy in England, Liberman developed an interest in photography, which eventually led to a career as editorial director with Condé Nast publications in New York. He turned to sculpting relatively late in his life.

“His works are at the Tate [in England], in other important collections, and here,” Feldman told us. “He works with aluminum tubing and like Louise Nevelson he uses one color, but his colors are very bright.” The sculpture before us was painted in a bright red. “He really liked the idea of using modern materials for a modern age,” Feldman added. His assemblage of tubes looked to me like a rocket about to be launched from a nest. “It has a vertical thrust to it, for sure,” Feldman commented.

Perhaps the most impressive pairing in the Sculpture Garden—certainly from the standpoint of size—are the bronze sculptures by Henry Moore (1890-1986) and Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975). I was particularly curious to hear Feldman’s commentary about these sculptures because she had worked at the Henry Moore Foundation in London for 18 years, first as a curator and later as head of their collections. She had traveled to 28 countries installing his sculptures. Feldman, daughter of a Jewish father and Christian mother, has been with the San Diego Museum of Art for approximately five years – a homecoming, one might say, because she grew up in San Diego, and was graduated from Kearny High School, before studying art at UCLA and later at the Courtauld Institute of Art at the University of London.

Feldman told us that Moore and Hepworth “were famously friends and rivals throughout their entire lives. For many years, they worked parallel to each other. They were exploring ways of opening out forms. Henry Moore started dividing his figures and you can see that in this two-piece figure (“Reclining Figure, Arch Leg,”) a wonderful chasm coming between the forms, making them resemble shapes in landscapes. You can imagine it being a series of mountains.” Moore’s piece, suggesting a woman’s torso and arched leg, is the largest sculpture in the garden, dominating the landscape. Next to it is Barbara Hepworth’s “Figure for Landscape” in which Hepworth “has hollowed out this form so it becomes almost like a ghost. There is this idea of the relationship between man and nature in both of these sculptures.”

Given the empty spaces that both artists purposely leave within their sculptures, “you can look through them; the landscape pervades the art; it comes right through,” said Feldman. “The Henry Moore is a wonderful piece to walk around. The landscape changes. It changes from a distance and up close. You can see all the detail and the texture. Some parts are very smooth. You can see the green of the cast coming through, the patina, and the very dark brown as well.”

I asked if, as the former head of collections of the Henry Moore Foundation, she would tell us more about the sculpture in the context of Moore’s career.

“This was made in 1969 and at that time he was very interested in this idea of relating figures to landscape, but also his figures were in demand in these very urban settings,” she replied. “He was thinking how can he make a figure work in a modern architectural setting, and so he started using bolder, more abstracted shapes in his figures so they could hold their own. He made them larger, so they would have more of a physical presence. Yet they still are recalling the landscape and still recalling the figure.” The massive sculpture before us, she added, “is definitely a head, shoulders and a torso coming through. … There are related pieces which are very interesting. For example, he has just this end-leg piece as a carving in black marble called “Arch” and he made this particular sculpture in three different sizes.”

Could Feldman please tell us more about Moore’s and Hepworth’s rivalry and companionship?

“They both came from the north of England from towns—Henry Moore from Castleford, which is a coal mining town, very industrial, and Barbara Hepworth came from Wakefield, which was six miles away! They both went to study at the Leeds School of Art, which was in the nearest big town, and then they both went to the Royal College of Art in London, within a year of each other. Henry Moore started first and then he went to London, and she followed him there. He was creating carvings first of all, these opening out forms. He said that making a hole in a sculpture was a revelation because you have a space coming through, and she did the same thing at the same time. They both experimented with strings, putting strings in their sculptures at the same time. In the 1930s they lived almost next door to each other in a neighborhood in Hampstead in North London. Another neighbor of theirs was [avant-garde artist] Naum Gabo, and [painter Piet] Mondrian came over. A lot of the artists and architects and intellectuals were fleeing Europe in the 1930s and a lot of them came to this suburb of Hampstead. So, there was this huge dialogue and exchange of ideas and it was a really exciting moment in England for the arts. [Architect Walter] Gropius came over and a lot of the artists from Germany came over. …

“When England entered the war, and London was being bombed in the blitz, Moore lost his studio/ home in London. It was damaged in the bombing. He also had a cottage in the south of England, in Kent, which he had to evacuate because the British were convinced that was where the Germans would invade England, from that coastline, so he lost both places at the same time. That was when he moved to Hertfordshire [to 70 acres of sheep fields] and Barbara Hepworth moved to Cornwall in the south of England, so they weren’t neighbors anymore, but they still were very close. She married [abstract painter] Ben Nicholson, and had triplets, so it was an interesting time.”

Their rivalry, while friendly, developed as “Henry Moore became increasingly famous and Barbara Hepworth tended to take a second seat,” Feldman said. “Part of that was due to the fact that she was a woman. Female artists were not given the same opportunities that male artists were, but also Henry Moore was involved in all kinds of projects all over the world, so his reputation began building on itself as cities got Henry Moore sculptures. He made over 1,000 sculptural ideas and many of them were cast in editions, so you can multiply those out. There would be six or nine of each one. And he made many thousands of drawings and graphics. There is a seven-volume resume just for the sculpture, another six for the drawings, and four for the graphics.”

I asked about the manner in which Moore went about his work.

“He had a very routine way of working,” Feldman said. “He didn’t like to vary it too much because if he kept to a routine, he could get more done. He had three assistants who helped him keep it going. He would get up very early and would work into the night. After it got too dark to sculpt, he would go into the house and draw.”

He drew his ideas from nature, Feldman said. “Say he would find a piece of stone or something in the garden that he liked the shape of, he then would make a plaster cast of that, maybe add a head, maybe other elements, and then he would make a plaster case of that [overall] shape. He would use that to make a small sculpture that he could hold in the palm of his hand. He worked on a very small scale. People always think of Henry Moore with these very big sculptures, outdoors, but 90 percent of everything he made was small enough to hold in the palm of his hand. Then his assistants would help him enlarge on those. He would have a middle size that he would call a working model, and that would be about three feet long, table top size, and then after that maybe only 10 percent would be enlarged to life size or bigger.”

Feldman came to work for the Henry Moore Foundation after the artist’s death, and never had the opportunity to meet him prior to that. As a San Diegan, she said, she would have liked to have escorted him along the rocks of Sunset Cliffs, as “he would have loved that.” He used to draw inspiration from the famous white cliffs of Dover, England.

Also in the Sculpture Garden are stainless steel sculptures by David Smith (1906-1965) and George Warren Rickey (1907-2002); a painted iron sculpture, “Spinal Column” by Alexander Calder (1898-1976) and a pedestal awaiting a new sculpture, “Rain Mountain” by Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988). Feldman expected it to be installed sometime during the month of November.

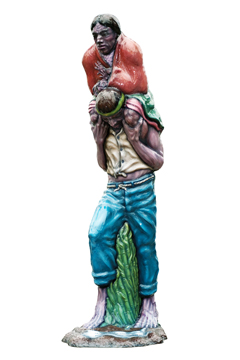

The unintended pairing that caught my eye, just outside the café, were a fiberglass sculpture, “Border Crossing” by Luis Jiminez (1940-2006), which depicts a man carrying his family on his back, crossing a river into the United States, and on a wall nearby “The Watchers,” depicting three faceless guards, by Lynn Chadwick, (1914-2003). Given today’s political context, in which a caravan of families from Central America is making its way to the United States border, where Border Patrol officers backed by the United States military are preparing to prevent the caravan from crossing into the United States, the two sculptures appear to be related.

Actually, they are not, said Feldman. It is just happenstance. Chadwick’s piece “was made during the Cold War,” she said. “You have these very stark, hard geometric lines. These three figures watching; it has that definite chill of the Cold War.” She noted that whereas the “Border Crossing” is facing north—the very direction that migrants head in their journeys to the United States — “The Watchers” are looking to the east. “They are not meant to be watching them,” she said. “The reason for this site is that this is the west wing of the museum [where] we have this huge empty wall and it was just crying out for a piece of art.” She said the west wing of the museum was constructed during the same time period as when Chadwick created her art.

In front of the main building of the San Diego Museum of Art, moving from west to east, are “The Prodigal Son,” a 1905 work by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917); “Mother and Daughter Seated,” a 1971 sculpture by Francisco Zúñiga (1912-1998) “Solar Bird,” sculpted in 1966 by Juan Miró (1893-1983); “Odyssey III” by Tony Rosenthal (1914-2009), the fourth Jewish artist represented in the collection of outdoor sculptures, and “Big Open Skull” by Jack Zajac (1929- ), the only sculptor in the collection who is still living.

I asked Feldman what she hopes that visitors to the outdoor collection will remember about their encounter with these sculptures.

“The joy of sculpture, of art, in a public place and in the open air, that art is not just something to hang on the walls of museums, that it can be enjoyed out in nature, with light and weather affecting it, and it comes in many different sizes, forms, and materials, and it is a pleasure,” she answered.

Also, she noted, considerable construction work is planned in Balboa Park near the end of next year, to create a direct access route to a planned parking structure that is intended to eliminate some of the traffic congestion within the park. That construction will necessitate some of the outdoor sculptures to be removed temporarily, Feldman said, “but be assured we will be bringing them back!”

I’d recommend seeing them sooner rather than later.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com