By Donald H. Harrison

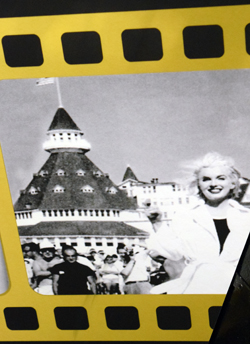

CORONADO, California – Three years after she converted to Judaism, actress Marilyn Monroe made the Billy Wilder comedy Some Like it Hot in 1959 with Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon. Now, almost 60 years later, this city across the bay from San Diego still remembers her vividly. The Hotel del Coronado, where the film was made, has pictures of Marilyn on display in a hallway, and the Old Town Trolley, which carries visitors on a two-hour tour of major sightseeing venues in San Diego and Coronado, plays a sound bite of her singing “I Want to be Loved by You” as it passes the red-turreted beachside hotel that was opened on Valentine’s Day 1888.

To remember Monroe for a vacuous blonde showgirl whom she portrayed in that movie would do her a grave disservice, according to an exhibit at the Coronado Museum of History and Art, in which she is remembered as a force majeure in the movie industry, and a woman of far-ranging intellectual interests. According to the exhibit, Monroe revolted against the system under which actresses were paid less than their male co-stars and in which neither actor nor actress had any say in what roles they would be cast. To demonstrate she wasn’t going to put up with it anymore, she refused for one year to appear in any 20th Century Fox productions, creating her own company—Marilyn Monroe Productions—in the interim.

“By 1955, after the commercial success of the Seven Year Itch,” 20th Century Fox capitulated, signing a contract in which Monroe was guaranteed $100,000 per movie and was given control over what project she would accept. Additionally, she was accorded input on directors and cinematographers. This marked the end of the traditional studio system of Hollywood, the exhibit noted. “Marilyn’s takedown of the studio system in Hollywood proved that her screen persona of being a ditzy was just that—an act,” according to the exhibit. “She was driven to be a successful dramatic actress.”

During the time that Monroe stayed away from 20th Century Fox, she took acting lessons at the Actors Studio in New York, which was run by the legendary Lee Strasberg and his wife Paula. During the Some Like It Hot movie – notable for Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon pretending to be chorus girls – Paula Strasberg was Monroe’s constant companion.

Another panel about Monroe told of her personal library, which included over 400 books on a variety of subjects. She had first editions of On the Road by Jack Kreouac; The Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison; and This House on Fire by William Stryron. Other books in the collection included works by F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Albert Camus, and Lewis Carroll.

Monroe was one of three Jews whose lives were briefly touched upon in the museum’s Coronado retrospective.

Another was movie maker Siegmund Lubin, who established a production company in Coronado in 1915 only to abandon it a year later. While it was in operation inside a large house located approximately where the Coronado Baptist Church sits today at First and Orange Avenue, the Lubin Studios made at least 43 movies, cranking them out at one point at the rate of 10 films a month, according to the exhibit. Most of those silent movies are no longer extant; in fact, only five are known to exist, and they are in the collection of the British Film Institute. Some Lubin film titles from the Coronado period were Billy Joins the Navy, The Slaves of the Harem, and the Sons of the Sea.

A brief video narrated by former KGTV newscaster Jack White said Coronado’s brush with the film industry began in February 1898 when Thomas Edison sent a film crew to San Diego where it made three short films. “Our clear dry weather permitted filming on most days of the year,” White said in explanation of Southern California’s subsequent attraction to a variety of non-Edison production companies. Southern California had various kinds of landscapes ranging from beach to mountain to desert. And a third reason was that it was far away from East Coast, where Edison interests attempted to enforce their claim that their patents provided them monopolistic rights to movies, movie technology, and movie viewing.

The third Jewish subject of the Coronado retrospective was opera star Ernestine Schumann-Heink (1861-1936), who had lived in La Mesa at one point of her career and later moved to a home at 800 Orange Avenue, the city’s main thoroughfare. The exhibit includes a recording of Schumann-Heink relating that she traveled to many wonderful places during her career. “However,” she added, “it is always such a pleasure to return to the home that I cherish on Orange Avenue in Coronado.

“I have always thought that homemaking makes for a broader outlook for any woman or artist,” Schumann-Heink continued. “Many times in the earlier days of my career, when I was preparing new operatic roles, I learned my roles while working at the kitchen stove, stirring the cooking with my right hand, while in my left arm I held a baby and in my left hand my opera score.”

There is an image in the exhibition of U.S. President Richard Nixon at a 1970 state dinner he hosted at the Hotel del Coronado for Mexico’s President Gustavo Diaz-Ordaz. Two other men are in the photograph with the two presidents, although they are not identified. Next to Republican Nixon I recognized as M. Larry Lawrence, who at the time was the owner of the hotel as well as a major contributor and activist in the Democratic party. Lawrence also was an active member of San Diego’s Jewish community.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com