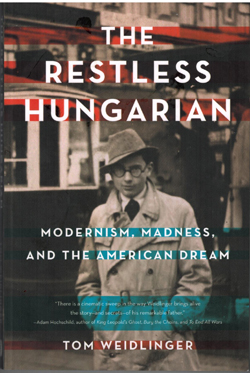

The Restless Hungarian: Modernism, Madness, and the American Dream by Tom Weidlinger; Spark Press, ISBN 9781943-006960; 278 pages plus photo credits, index, and acknowledgments; $16.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – It did not take me very long to decide that I did not like structural engineer Paul Weidlinger, who is the subject of this biography. It took me a little while longer to realize that his son, Tom, who authored this biography didn’t like him either.

SAN DIEGO – It did not take me very long to decide that I did not like structural engineer Paul Weidlinger, who is the subject of this biography. It took me a little while longer to realize that his son, Tom, who authored this biography didn’t like him either.

Describing his father’s voyage with some Communist friends in 1939 from an uncertain future in Hungary to Bolivia, the younger Weidlinger wrote:

One day, in the third-class lounge, the four boys were invited by a group of observant Jews to help form a minyan, the quorum of ten adults required for public prayer. They politely declined. Some time later my father made a drawing of his “coreligionists” on the Oropesa. It showed a huddled group under a flag with the Star of David. Most of the figures have large, grossly exaggerated noses. These figures are clearly Polacos, a derisive term widely used by Central European Jews for their Eastern European co-religionists. The Polaco stereotype was loud, coarse, uneducated, and untrustworthy. They were viewed as embarrassing reminders of ghetto Jewry from which most middle-class Hungarian Jews, including my father’s parents and grandparents, distanced themselves in their process of assimilation.

That passage did it for me. I understood that Paul Weidlinger was the kind of man who would deride other Jews in order to make himself more acceptable in the eyes of non-Jewish Europeans, who, as time later would tell, would support the ghettoization and mass murder of all types of Jews, no matter how “cultured” or “assimilated” they thought they were.

By the time Paul and Madeleine’s first child, Michele, was born, the family never spoke about being Jewish. That was one part of their identity that the couple wished to keep secret. In part, Tom explained, they were traumatized by what had happened to the Jews of Europe during the Holocaust that they had escaped. In part, they were arrivistes, claiming their place in Gentile American society, where Gentlemen’s Agreements often barred the doors to Jews seeking residences and job opportunities. However, to my mind, those were just excuses. Paul’s self-centeredness at the expense of his fellow Jews became utterly and disgustingly clear to me reading about that day on the ship.

From Bolivia, the Weidlingers immigrated to the United States, where, thanks to Paul’s proficiency as a structural engineer, they followed a capitalistic life, their pro-Communist sympathies now left behind. Paul collaborated with numerous famous architects on such structures as the Hirshhorn Museum on the National Mall; the Biencke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University; the CBS Building in New York City; the U.S. Embassies in Athens, Baghdad, and Jakarta; and the studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania, of the famed furniture artist George Nakashima.

Later, he was lured into top secret work for the federal government, figuring out how nuclear missile silos could be built strong enough to withstand a first strike by the Soviet Union, and then open up to permit the missiles to wreak their revenge on the adversary’s Communist government. At his large offices, Paul was the authoritarian, who would ridicule and yell at his subordinates. They nevertheless wanted to work for him because of his industrial genius.

Paul and Madeleine divorced after she was formally diagnosed with schizophrenia. Despite Madeleine’s mental illness, Paul abdicated the parenting of Tom (Michele was already grown) to his often unbalanced wife. The boy lived in terror of her, frequently cowering in a treehouse or on his small boat to keep away from her rages. He feared his mother and resented his father—who soon remarried—for abandoning him to her.

Paul Weidlinger was a man who could shed his religion, his political beliefs, and even his family, whenever such actions might profit him.

This is an unflattering, but quite candid, portrait of a self-centered genius, who left his family behind in psychological carnage. Daughter Michele committed suicide after murdering her young son. Somehow, son Tom kept his sanity; but his anger, it seems, won’t be sated while he still draws a breath.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com