By Lisa Shapiro

SAN DIEGO — My father dissuaded me from a military career when I was about thirteen. We had been walking along the beach in San Diego, enjoying a late summer’s evening. Fog covered the sunset and damp sand tugged at our steps. The receding waves drew my gaze toward the horizon, and I yearned for all the things still out of reach, like confidence, and the power to realize my dreams before they faded like the footprints behind me. It was the first time I’d ever thought seriously about joining the armed services. Instead, I was encouraged along a more traditional academic path, and in retrospect, I can see how I flourished without the constraints of military hierarchy. Yet the lure of service stayed with me, including the desire to put my body and mind in service toward something greater than myself.

SAN DIEGO — My father dissuaded me from a military career when I was about thirteen. We had been walking along the beach in San Diego, enjoying a late summer’s evening. Fog covered the sunset and damp sand tugged at our steps. The receding waves drew my gaze toward the horizon, and I yearned for all the things still out of reach, like confidence, and the power to realize my dreams before they faded like the footprints behind me. It was the first time I’d ever thought seriously about joining the armed services. Instead, I was encouraged along a more traditional academic path, and in retrospect, I can see how I flourished without the constraints of military hierarchy. Yet the lure of service stayed with me, including the desire to put my body and mind in service toward something greater than myself.

I began teaching at a community college in San Diego a few years after the September 11th attacks, and found myself facing classrooms full of veterans. The desire to understand the military experience came rolling back. There was a depth of emotion roiling in my students. Their uneasiness at being back in civilian life was a constant undercurrent in our conversations. One of the authors who has helped me understand the intersection between civilian and military life is Sebastian Junger.

Junger’s bestseller, The Perfect Storm, is a beautiful example of creative non-fiction, and the book quickly became part of the reading list in my freshman composition classes. In compelling prose, Junger describes how three storm systems locked in place, winds meshing like gears in a terrible and destructive mechanism. He delves into the physics of wave formation, and demonstrates the point at which a boat cannot right itself. He explains the moment when a drowning person can no longer resist the physiological imperative to gasp for air, even underwater. Junger wants to understand the motivations that drive humans into danger. In his 2016 book, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, he explores how people can pull together, especially in crisis, and he draws on his own experiences as a war correspondent in Afghanistan.

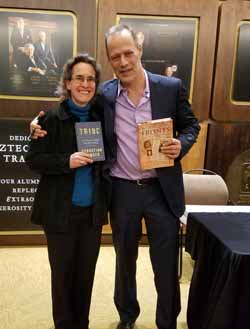

I heard Junger speak last month at San Diego State University. The event was sponsored by the university’s alumni, the campus veterans center, and the USS Midway, a former U.S. aircraft carrier now a maritime museum in San Diego. In his resonant bass voice, Junger described how hard it was to find a hiding place when his unit was facing an ambush. Instructed to hide under a large rock, he refused. “I knew there were spiders under there,” he said. Admitting his fear of spiders to young, battle-hardened soldiers may have been a mistake. The men in his unit tried to think up more ways to scare him, including tarantulas fashioned from pipe cleaners. The pranks reflected the close camaraderie between the men during their dangerous missions. In the unit, everyone had a job, and everyone was necessary for survival.

Junger’s choice of career was shaped by his father’s immigrant experiences. His family, which is partly Jewish, fled first from the Spanish Civil War, and then from Europe to escape the Nazis in World War II. Growing up in a liberal household in suburban Boston, Junger was drawn to the stories his family didn’t want to talk about – stories of war. After studying cultural anthropology, he turned to journalism. “War is compelling,” he said, but instead of studying it from a distance, he went to see combat for himself.

“They build these little hooches, and they’re really cramped,” he told the audience gathered at San Diego State’s alumni center. He described how, lying in his bunk, he could stretch his arm and touch three other men. In such tight proximity, and with survival on the line, there wasn’t room for discord. The men in his unit didn’t have to like one another, but they had to cooperate. This shared unity, Junger believes, may help people endure hardship, and may also hold the key to helping soldiers as they return to civilian life. Junger is honest about his experiences with PTSD, citing as an example the panic attack he suffered when, at a Paris café, he watched two people struggling to lift a mattress. “It sagged like a body,” he said. He could no more control the surge of adrenaline than a drowning person could stop the urge to inhale.

In Tribe, he quotes Dr. Arieh Shalev, a researcher with extensive knowledge of PTSD. Shalev’s work indicates that when the public shares the experience of war, they are better equipped to help soldiers transition back to civilian life. Junger cites as an example Israel’s Yom Kippur War of 1973, when soldiers were fighting close to home. Because there wasn’t much distance between soldiers and civilians, they shared a common cause. That context runs deeper than what Junger calls “token acts,” such as thanking a service man or woman for service, or offering a military discount at the market. Shared experiences close the gap between those who fight and those who don’t.

As I worked with my students on their essays and resumes, I asked about their experiences and skills. Many of the veterans stated they’d been advised not to talk to civilians about their service. “Don’t hide it,” I insisted, and explained that military knowledge could enhance their connection with a civilian workforce. Their resumes got longer, and their stories became more detailed.

Like Junger, my background is liberal, and Jewish, and my culture holds learning in high regard. By following an academic rather than a military path, I was spared the crippling physical and emotional effects of war. As I listened to Junger, it occurred to me that veterans are like immigrants, caught between two cultures, and changed by both. And like refugees, they may yearn for a way of life that is still very much a part of them. It isn’t easy to shed the values and habits of a tribe just because that group has disbanded. In the classroom, I am powerless to stop the triggers that light up like flares inside the bodies and minds of my student veterans. Yet having read Junger’s work, and the writing of other war researchers, I am better equipped to listen when veterans share their stories, and I am better at reading the deeper currents in our conversations.

*

Lisa Shapiro is the author of No Forgotten Fronts: From Classrooms To Combat, published in 2018 by Naval Institute Press. One may visit No Forgotten Fronts on Facebook, and visit the website at www.NoForgottenFronts.com.