By Donald H. Harrison

EL CAJON, California — “What’ll it be, sir?”

“I’ll have a beer and where’s that Torah discussion group?”

“Over there, sir. And here’s our beer menu.”

Once a month, members of Tifereth Israel Synagogue sample the selections at one of San Diego County’s burgeoning microbrewery industry’s locations, where they socialize, enjoy a beer, and discuss a Torah topic. Started several years ago by the late Rabbi Leonard Rosenthal, the “Torah on Tap” program has been continued by successor, Rabbi Joshua Dorsch. On Monday evening, May 13, thirteen souls and this reporter gathered at URBN at 110 N. Magnolia in El Cajon, where the Creative Creature Brewery shares space with the beer and pizza restaurant.

“I think beer and Torah is a great idea,” says Norman Kort, a board member at Tifereth Israel Synagogue in neighboring San Diego. “I wouldn’t come out for a beer normally, but this is a good excuse – and this particular establishment is good because there is food as well. Some of those that we have been to, don’t have food.”

Indeed, URBN has a number of dairy and veggie pizza selections. Sharing its space in downtown El Cajon is Creative Creature Brewery, one of approximately 150 microbrewery locations in San Diego County.

“Sometimes a synagogue can be an intimidating place,” comments Rabbi Dorsch. “To teach Torah to members of our community outside of the synagogue is a wonderful way to connect to people in a different environment; they can sit back, feel a little more relaxed, and really enjoy each other’s company and have good conversation.”

Rabbi Dorsch said that his previous congregation – Congregation Beth El in New Rochelle, New York – had a similar program, but “I will say that the beer selection in San Diego is way more exciting than it was in Westchester County (New York).”

As it is done by Tifereth Israel Synagogue, the rabbi gets to pick the topic, which, in Dorsch’s case, tends to be “whatever is timely. It could be something from current events; it could be something from the Jewish calendar; it could be a parashah (Torah portion.)”

On this particular Monday evening, the rabbi chose to discuss the counting of the Omer over the 49 days between Passover and Shavuot, the latter of which Jews celebrate as the day that God gave the Torah to the Israelites.

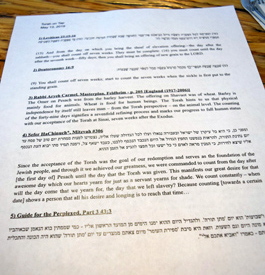

So, two sheets of paper were placed before the mixed group of men and women. On one were brief selections from Torah and commentaries on the subject of counting; on the other was a list of beers from which to choose. (In fairness to the non-alcohol drinkers in the group, it should be stated that URBN also serves soft drinks.)

In preliminary conversation, the group discussed the story of Rabbi Akiva, the great sage who taught during the First Century of the Common Era. It was said that he had 24,000 students who died during the early weeks of the counting of the Omer. While some commentators thought that the students’ deaths might have been caused by plague, others thought it was divine punishment for treating each other so poorly. “They put learning Torah over derech eretz (ethical behavior),” Dorsch explained.

On the 33rd day of the counting of the Omer, known in Hebrew as Lag B’Omer, the plague was lifted. In mourning for Rabbi Akiva’s students, traditional Jews observe some restrictions: They don’t shave, they don’t have celebrations; and they refrain from weddings. However, Rabbi Dorsch instructed, “exceptions are made for such celebrations as Yom Ha’atzma’ut (Israeli Independence Day) and Yom Yerushalayim (Jerusalem Reunification Day).”

The discussion group debated whether so many deaths in so short a time period really was possible; that was an average of over 600 deaths a day, one congregant pointed out. Rabbi Dorsch suggested that a plague, especially in times when knowledge of sanitation and medicine was rudimentary, could indeed cause thousands of deaths. Agreeing, some members recalled from history that the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 killed millions of people around the world. Rabbi Dorsch commented that conducting a funeral for even one person is a significant undertaking; imagine how difficult it would be for Rabbi Akiva to have presided over so many.

When some students questioned whether Akiva really had 24,000 students at one time, Rabbi Dorsch said it is possible that the number has been exaggerated. He added that Rabbi Akiva was so revered a scholar and teacher that many legends have been attached to his name, none perhaps more terrifying than the story of how Romans flayed the skin from his body for continuing to teach the Torah. As is told in the martyrology service on Yom Kippur, even as he was dying, Akiva was exultant. How was this possible? his torturer asked him. Akiva responded that the Torah teaches that one should love God “with all your heart, with all your soul, and all your resources,” (Deuteronomy 6:5), and until then, he never knew how one could love God “with all his soul,” but now, he said on the point of expiring, he understood.

On Lag B’Omer, the day that the plague ended, Jews enjoy a general celebration. Children who otherwise would have had their third year haircut in the preceding 32 days now receive their haircuts, often to great celebration, and bonfires are lit in mystical tribute to one of Rabbi Akiva’s students who survived – Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. According to legend, Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, while hiding in a cave from the Romans, compiled the Zohar, a fundamental work of Kabbalah, which he later revealed on Lag B’Omer, the same day that he died.

Preliminary discussion having thus transpired, Rabbi Dorsch distributed sheets of paper on which were quoted Torah passages from Leviticus and Deuteronomy, as well as quotations from the Sefer HaChinuch (a 13th Century anonymous Spanish commentary on the Torah’s 613 commandments – of which the counting of the Omer is the 306th commandment), and from the works of such other rabbis as Maimonides (circa 1138-1204); Joseph Soloveitchik (1903-1993); and Aryeh Carmell (1917-2006). The Torah portions contained the instructions to count the seven weeks between the festivals of Passover and Shavuot. Maimonides suggested that the counting of the Omer was ordered “in order to raise the importance” of the giving of the Torah on Shavuot, “just as one who expects his most intimate friend on a certain day counts the days and even the hours.” The Sefer HaChinuch agreed, saying counting the Omer “manifests our great desire for that awesome day which our hearts year for just as a servant yearns for shade. … (C)ounting show a person that all his desire and longing is to reach that time.” Rabbi Carmell elaborated on this theme, writing: “The counting of the forty-nine days signified a sevenfold refining process and marks our progress to full human status with our acceptance of the Torah at Sinai, seven weeks after the Exodus.”

Rabbi Solovitchik suggested that the act of counting invokes both the past and the present. “At any position in which you find yourself counting, you have to be aware of two things: of the preceding position and the following position,” he wrote. “For instance we counted last night “lamed-gimmel [lag] ba’omer, thirty-three days in the omer. However, we could not have arrived at this position from nowhere, ex nihilo. When we say lame-gimmel, thirty-three, we ipso facto state that this position was preceded by thirty-two previous positions. .. At the same time, however, we also know that “thirty-three” is not the last station … In other words, any act of counting embraces retrospection as well as anticipation … And that’s why sefirah, counting, is so prominent in the Halacha (Jewish law).

As the group assembled, according to Rabbi Dorsch, his preschool aged son Nadav, was watching Sesame Street on the family’s television monitor. A favorite character in that much beloved show is the “Count,” who laughs joyously as he counts everything, possibly unaware that he is acting both in retrospection and anticipation.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com