By Oliver B. Pollak

JACKSON HOLE, Wyoming — My story “Hannover to Terezin, roundtrip please,” appeared on San Diego Jewish World on June 2, 2018. It has had remarkable unexpected consequences.

My interest in Theresienstadt (the German name for the Czech Terezin) started in the 1980s when my mother gave me my grandfather’s papers. They included his 1881 birth certificate indicating that his parents were “Judische” and his 1956 death certificate issued in Palm Springs. He had three grandchildren, including me. I well remember his funeral.

In between the life and death bookends were documents about education, World War I, employment, the Nazi era and an Ehrenkreuz für Frontkämpfer (The Honor Cross of the World War 1914/1918) awarded to honor WWI veterans shortly after Hitler took office in 1933, an array of official anti-Semitic government forms and a yellow cloth ‘Jude’ star. Most pertinent was a diary or letters written on hotel stationary about his incarceration in Theresienstadt. What emerged was “A Medical Memoir of Terezin/Theresienstadt Concentration Camp by Felix Bachmann, M.D.” that appeared in 1997 in Kosmas: Czechoslovak and Central European Journal and reprinted in 2014 in Michael A. Grodin’s, Jewish medical resistance in the Holocaust.

My Opa, Felix Bachmann, earned his medical degree in Germany. He practiced obstetrics and gynecology, was a ship’s doctor on the US Grant crossing the Atlantic, and a MASH surgeon in the German army until he got a shrapnel wound in his right arm. Up to the Nazi era, he served as a disability examiner in the German health and disability insurance system. Incarcerated by the Nazis, he served as a physician in the Terezin/Theresienstadt hospital from 1942 until liberation by the Russian Army in 1945,

Theresienstadt has been called Hitler’s Gift to the Jews. It gave rise to two books with similar titles. Norbert Troller (1896-1981), a Czech architect, who endured Theresienstadt for two years, emigrated to the United States. He curated an exhibit of his concentration camp experience at the Yeshiva University Museum in 1981. He published Theresienstadt: Hitler’s Gift to the Jews in 1991. George E. Berkley published Hitler’s Gift: The Story of Theresienstadt in 1993. The Red Cross visited the model facility flattered by the film Der Führer schenkt de Juden eine Stadt (“The Führer Gives a City to the Jews”). My favorite dark double language pun derives from “Hitler’s gift to the Jews.” In German, “gift” means poison.

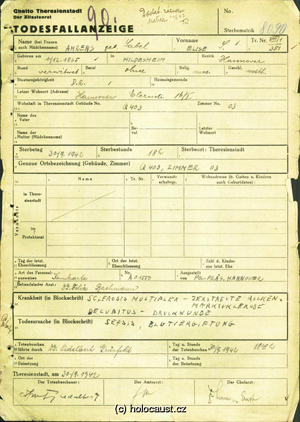

Jürgen Wessel, a researcher, googled Terezin, Theresienstadt and Hannover in preparing for the July 11, 2019 installation of Stumbling Stones or Stolpersteins. He found the San Diego Jewish World story and sent me a copy of the death certificate of Elise Ahrens (nee Sabel) to be honored and remembered by the stone. Her husband August had died in 1917. Born in 1865 she died shortly after arriving in Theresienstadt in 1942. My grandfather, the Behandelder Artz, the attending physician, signed Elsie’s death certificate. She died of Sepsis, Blutielgiftung, blood poisoning.

The artist Gunter Demnig, born in Berlin in 1947, opened a studio in Cologne in 1985 and in 1992 started creating Stolpersteins (Stumbling Stones, Memory Stones) to commemorate and honor Jews who were wrenched out of their homes and murdered. Demnig quoes the Talmud on Stolpersteins, “a person is only forgotten when his or her name is forgotten.”

The over 70,000 memory stones are in at least 26 countries and over 400 German cities, towns and villages. On Thursday, July 11, twenty-two stones will be placed in various Hanover sidewalks. Each ceremony will take twenty minutes.

The interest in Theresienstadt, part of the momentous monstrosity, has been unrelenting. Survivors and scholars have produced at least twelve volumes in English and German since 1997. This may be attributed to Theresienstadt not being a death or labor camp, thus having more survivors. The “model camp” is an hour drive from Prague. Visiting a museum or historical site is more than dark tourism, it is another way of remembering, not forgetting.

*

Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com