By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – Comic books often have their sequels. So too do appearances at Comic-Con.

At the current Comic-Con, a panel on art in the Holocaust was largely a repeat of last year’s panel – with some new information. Meanwhile, an independent exhibitor, Miriam Libicki, about whom two stories have appeared in this publication from past Comic-Cons, was back at a table in the exhibition hall, telling passersby about her latest graphic book.

The panel on the Holocaust was moderated by Stephen D. Smith, executive director of the USC Shoah Foundation Institute, which, thanks to a grant from movie producer and director Steven Spielberg, has recorded many thousands of hours of testimony by Holocaust survivors, which are made available to the public through the Foundation.

Sandra Scheller appeared at Comic-Con last year with her mother, Ruth Sax, with whom she had collaborated on the memoir Try to Remember: Never Forget. This year, she showed a clip of her mother, who had died in the interim, addressing the previous year’s Comic-Con. Here is a link to a story about that appearance.

Scheller also showed examples of Nazi propaganda drawings and posters in which caricatures of Jews made them look ugly, deformed, and grasping. Scheller announced that the Chula Vista Library will have an important exhibit about the Holocaust beginning in January of 2020, in which the lives of 10 local Survivors are to be highlighted.

Another returned panelist was Esther Finder, president and founder of Generations of the Shoah-Nevada, who once again compared and contrasted the Nazis’ idea of a superman or “ubermensch,” with the Superman of comic book fame created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. While the Nazis’ superman wished to trample underfoot anyone considered to be lesser beings – including Jews, Gypsies, Slavs, people with physical and mental disabilities, and LGBTQ persons – the Superman of the comics was compassionate, using his strength and powers to help those less fortunate.

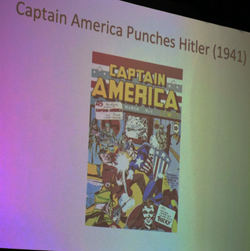

New this year to the panel was Matt Dunford, chairman of San Diego Comic Fest, which devotes itself to comic book art, stories, and history. His own special interest is World War II stories. Like Superman, he told a Comic-Con audience, Captain America also was created to counter Nazis propaganda. One of the earliest covers of the Captain America comic, published before U.S. entry into World War II, shows the super-hero punching Adolf Hitler in the face.

Like Superman creators Siegel and Shuster, Captain America’s creator Jack Kirby was Jewish. He was born in 1917 as Jacob Kurtzberg. The earliest number of Captain America came out before the United States entered World War II, with Kirby hoping to stimulate anger and repulsion about the way the Nazis were treating Jews and other civilians.

The upshot of the panel was that whether in the hands of the bad guys (Nazis) or in the hands of good guys (patriotic Americans) cartoon images and other drawings conveyed some powerful emotions before and during World War II, helping to win support for their respective governments’ policies.

Graphic artist Miriam Libicki had been the subject of San Diego Jewish World articles in 2017 and 2018, in which were highlighted her graphic novels Jobnik and Ruchie’s Job.

This year, based on a scary experience she had at her home in Vancouver, British Columbia, she published Who Gets Called an Unfit Mother.

She said that she lives in a quiet neighborhood, where private and semi-private green spaces are surrounded by the windows of the townhouses arrayed around them. On one occasion her preschoolers were playing outside together. When the Maya, 5, came home, Libicki asked where was her little brother Mati, 2. The boy shrugged his shoulders, saying he wouldn’t come home with him. Libicki went to retrieve him from outside, only to find a social worker holding him by the hand and giving her a “death stare.”

She later learned that an unidentified person had telephoned a representative of child protective services, claiming that Libicki was neglecting her children. A social worker then told Libicki that her fitness as a mother would be investigated. Of course, the prospect of having one or two children taken away from her practically paralyzed Libicki with fear and paranoia.

Although this drama was unfolding in Canada, Libicki felt it ironic that at the same time next door in the U.S. authorities had announced a zero tolerance policy for some immigrants and were separating the families of asylum seekers.

The two occurrences became conflated in her mind. She described Canadian child protective services as a “punitive system – either they do nothing or they confiscate the children. It is not about helping families, or keeping them together, or giving them resources.”

In the book, she describes and illustrates her feelings moment by moment until the time that she received an official letter with the announcement that the case was closed, with no further action contemplated.

Although “it did turn out okay,” the period under which she was under investigation was emotionally traumatizing. She kept her eyes glued on her children for the entire time, possibly transmitting some of her fears to them.

“It’s a terrible feeling — your children being lost or given to strangers who don’t care about them,” Libicki said.

The system ostensibly set up to help children really doesn’t do so, she added. “One of the most long-term psychologically damaging things you can do is to take a child away from a long-term relationship,” she said. “It can impair the child’s emotional and cognitive development.”

Since the incident occurred, Libicki penned a 4-part illustration for a series in The Nib, a political cartooning site, about perceived abuses in the child protective services system. She said no other family should have to go through what her family did.

Further, she said, as traumatizing as it was for her, her situation was relatively benign compared to mistreatment of families in which parents and children are separated by U.S. border authorities.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Thank you a million times for writing about our panel, Art During The Holocaust. We love seeing you. Until next year….. Sandy