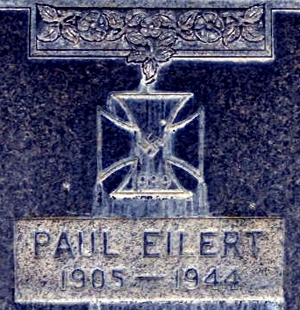

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah — Paul Eilert died of cancer in a Utah hospital in 1944. Eilert was a German POW. He is buried in a section reserved for POWs in Ft. Douglas, Utah. There are 20 other German WWII interments in the Utah U.S. military cemetery. His is the only one with the Knights Cross and Oak Leaves, a very, very high military decoration for his actions against the enemy, clearly carved with a swastika inside the cross. Of the 800 German POW deaths in the U.S., from the lowest rank to generals, his unusual stone is the only one with the Knights Cross on his tombstone. Research, so far, has found his name, nowhere. Paul Eilert, the Swastika in the U.S. Military Cemetery, is a mystery.

A few weeks ago, I was contacted by a Jewish Professor at a Utah university for assistance. The professor learned of the Swastika in the U.S. cemetery. He was outraged and wanted to get rid of it.

I knew little about the WWII German POW story in the U.S. There were thin stories I had heard about where I had lived in Rockville, Md. of a German POW camp nearby. The little bits of barbed wire I found on the back acres of my house, the site of a former farm, I imaged were parts of a German POW enclosure. They were not. But there was a German POW labor camp about three miles away in Emory Grove. Every day, local farmers would go to the camp and get two or three POWs for farm work. They would be given lunch, a small amount of pay for their day, and sent back to Emory Grove.

In College, I learned of something much different. I rented a room in a basement from a Polish lady who came over after the War. Her German lover, who came over periodically to drink beer, of which I shared one or two, was a decorated veteran of Rommel’s Afrika Corps. He vaguely told me, after an extra beer or six, of summer camps in Arizona where young German heritage Americans trained. They were indoctrinated with Nazi ideology and prepped for the return of National Socialism to Germany and for its place in America.

His blue eyes and grey splattered blond hair bespoke his Aryan genetics. He hated the neo-Nazis. He had no hostility to me though I was a Jew. I did not connect the dots. I thought it was the beer speaking of an old German soldier who was now a respected American scientist.

Between 1942-1945, 450,000 POWs, almost all of them Germans, were brought to the U.S. The British asked for American help holding POWs because their beleaguered little Island barely had room and ability to feed its own struggling war population. The Liberty ships went over with supplies and back with prisoners, who were scattered all over the U.S. Utah received 13,000 Germans.

It was not the first time that Utah had received German POWs. In WWI, German Naval POWs were sent to Utah and Ft. Douglas. There were not too many German POWs. Ft. Douglas held mostly German aliens and even some German Americans who were caught up in the anti-German hysteria of WWI. Some of them died in the American Utah War Camp prisons. They were the first to be buried in the Ft. Douglas Cemetery section reserved for Germans.

In 1933, the only memorial to German War dead in the U.S. was erected at the cemetery site in Ft. Douglas. Known as the Peace Memorial, it was erected by German Americans with support from the American Legion. 21 names were placed on the memorial. Only 1 was a German POW. The other 20 names were interned “enemy aliens” who had died, imprisoned in Ft. Douglas.

Near the memorial are the graves of the 20 German POWs from WWII. Nine were killed on a hot July night in 1945. Time Magazine called it the Midnight Massacre. Private Clarence V. Bertucci, an American military guard, climbed into the guard tower overlooking the German POW tents in Salina, Utah for his midnight to sunrise duty. He loaded his browning machine gun and in 30 seconds, sprayed the tents with the sleeping men. Nine were killed and a score were wounded. His heart’s desire to kill Germans was finally fulfilled.

Bertucci, found insane by a military inquiry, was carted off to a hospital for a few years.

At the funerals, the German dead were dressed in G.I. uniforms. Their caskets were covered by newly minted German, de-Nazified, flags. German-speaking American guards made sure no Nazi songs were sung, no Nazi secret ceremonies were presented. The men were interred.

Within the camps, American information officers, especially the Jewish officers, caused extreme consternation among elements of the prisoners. They attempted to introduce the POWs to American concepts of democracy and toleration.

Not all the POWs were die-hard Nazis. They wanted nothing to do with Nazism. For their opposition, the Nazis in the American German POW camps murdered their fellow prisoners. 14 German POWs were executed by the U.S. for murdering other German POWs.

By early 1946, all the Germans had been repatriated to Europe. Most ended up for a few more years in England or France in less than stellar labor camps before being released to Germany.

I contacted a friend, a Christian who was an avid collector of Nazi memorabilia. He had created a short-lived Holocaust Museum in Massachusetts that I helped fund. Daryl, I asked, “take a look at this picture of Paul Eilert’s tombstone.” Daryl immediately recognized the Knights Cross. He said about 7,000-8,000 of the K.C.s were awarded. But he also noted, Eilert’s K.C. had Oak Leaves attached.

Daryl said there were only about 800 K.C.s with Oak Leaves ever awarded. “Eilert must have been involved in some deep Sh… Among Nazi enthusiasts, picture trading cards had been created for the recipients of the K.C. Recipients of the K.C. and Oak Leaves were rarer than hen’s teeth and very desirable.” He did not have one of Eilert.

Who was Eilert? He was born in Berlin in 1905. His death certificate said he had been a factory worker. He was single. Curiously, he was old for only obtaining the rank of corporal. The Germans were not desperate for manpower when Eilert would have been captured.

The professor noted under the Swastika on his memorial, the date of 1939. He said that correlated with the beginning of the Holocaust.

Did Eilert receive his award for Holocaust-related activities? Searching further, after the invasion of Poland, September 1, 1939, the German Government created an updated K.C. with the date under the Swastika of 1939 for all subsequent awards. Was Eilert’s K.C. for anti-Jewish actions? Probably not.

The strange thing about Eilert’s funerary arrangements was that his fellow POWs pooled their money to buy him a large funerary stone carved with the K.C. and Oak Leaves. They honored him above all others, but for what….?

With the closing of Ft. Douglas as an active military base, all the records about the German WWII military burials have disappeared. Eilert’s name is not listed in the records that I have searched for recipients of the K.C. with Oak Leaves. Perhaps Eilert was not his real name for a reason.

Why did an unknown American military base commander permit the only Swastika in an American Military Cemetery to be placed so near to American war dead?

I shared with my Jewish professor friend our mutual disgust with the symbol of hate honored in U.S. soil. Learning about him made me shiver with blood that ran colder than cold. I warned my professor friend, before he goes off and files his threatened lawsuit to have the Swastika removed, he needs to search much more.

Nothing is as simple as what it seems on the surface.

*

Jerry Klinger is President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation.

Paul Eilert never received the KC, let alone with Oak Leaves, and those are no oak leaves in the headstone, which was purchased by his kameranden as a monument to their love and admiration of him. Nothing sinister going on here.

Very interesting. There were German POWs in Sioux Falls during the war. I remember seeing them at the Army Air Tech. Airbase.