PRAGUE, Czech Republic — On September 11, 2001, I gathered together the actresses of Raise Your Spirits Theatre in Gush Etzion, Israel We had all followed the horrific events of the day happening in New York.

We had created our theater troupe that summer, in the midst of a bloody intifada in Israel, and had made a decision at the time to not cancel rehearsals or performances on the day of a terror attack. We opened our rehearsals with the reciting of Psalms, as there was always someone in need of healing, and we prayed for our safety and the safety of our soldiers. Two women from Efrat, Sarah Blaustein and Esther Alvan, were among the newest terror victims before we began our project, intended, like its name, to raise spirits.

But our resolve to not cancel notwithstanding, nothing of this magnitude – the sheer numbers – had happened thus far.

I told our actresses, “I only discovered a month ago, through a distant cousin, that I had relatives who died at Theresienstadt. They may have been theater people. We’re not at Theresienstadt and this isn’t the Shoah, and we’re performing. But anyone who prefers not to, can sit it out.” No one chose that option.

On the advice of one of our rabbis, we opened the show with the reciting of Psalms, with almost 500 women — the whole audience and cast – and retained, to this day, the custom of opening every show with the reciting of a perek in Tehillim. It was also the first time we ended the show with the singing of “Hatikva” and “Ani Maamin [“I believe”],” also a custom we have retained to this day.

I knew then that, one day, I would want to visit the “model” concentration camp created by the Nazis, where my relatives died, or which was their last stop before Auschwitz. Theresienstadt is less than an hour away from the beautiful city of Prague.

Back to Roots

My husband was born in Slovakia after the Shoah, when it was called Czechoslovakia, to parents who survived the Shoah being hidden in an underground storeroom in Trnava, about 30 miles from Bratislava. He is descended from Rabbi Yom Tov Lipman Heller, zt’l (1579—1654), author of Tosfos Yom Tov on the Mishnah, who studied under the Maharal of Prague, so his connection was also close up and personal.

From the moment we entered the city, I felt the presence of the Jews who are no longer there. I wondered about every Czech person we met (and they were all lovely). Where were their parents or grandparents during the Shoah? Did they help or hide any Jews, or did they stand along the sidewalks and cheer the Germans as they entered the city? I loved the magnificent architecture, taking my photo next to a statue of Franz Kafka, walking the picturesque streets, but my soul couldn’t escape the past.

We stayed at the beautiful old-world style Hotel Caruso (with kosher breakfast) and our first day in the city was spent in the Jewish Quarter, visiting all the once exquisite synagogues. Today they are mostly museums, though there are services in a few of them on Shabbat. One of the most haunting exhibits was in the Maisel Synagogue, which in addition to housing fascinating historical and religious artifacts, with meticulously recorded history of everything, had as its centerpiece a three-dimensional film-like presentation of the Jewish Quarter as it was once upon a time, including those synagogues that no longer exist. The presentation was so realistic, one could feel oneself walking through the streets. I watched and thought, what distant cousins of mine ran along these cobblestoned streets, where did their children chase a ball or ride a bicycle? I asked a tour guide how so many religious artifacts were preserved, and she said that Hitler had planned to create a museum of the Jews, as an extinct people.

A Memento and a Memory

Our first stop that morning had been in an antique shop, as I was seeking a memento, a special gift for our daughter-in-law, who had just turned 30. I purchased a lovely ring, more than a hundred years old. The proprietor told us that the items in the shop were either from private collections or bought at auction. I asked her if the items that were auctioned might have belonged to the Jews before the war. She said yes. At least one of those (possibly stolen) rings has achieved redemption, as it now sits on the hand of a lovely young woman in Eretz Yisrael.

The main prayer and other downstairs halls of the Pinkas synagogue, other than the bima and the Aron Kodesh, has only walls with the names of Jews who had been deported from Prague and the area – 77,000. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, more than a quarter of a million Czech Jews were murdered in the Shoah and more than 60 synagogues in the Czech lands were destroyed. Somewhere on those walls may be the names of my relatives.

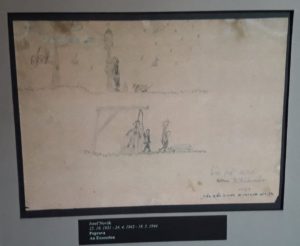

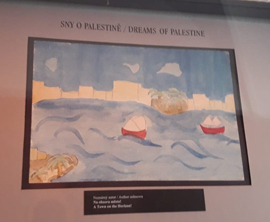

The upstairs has a display of drawings and paintings done by the children of Theresienstadt. Artwork that revealed fears, memories, impressions of real life, and dreams for the future, like the child who painted boats on the sea, on their way to the land of Israel. There are even pictures of transports and executions. Their painting teacher, artist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, based on the information posted in the gallery, tried to help them survive those difficult times by using various art methods with them. Having taught drama in a program for the expressive arts, I can only shudder at the thought of this ultimate experience, for both the teacher and her students, in art therapy. The majority of these children perished.

A Mikva and a Cemetery

One of the highlights of our tour was the ancient mikva that one reaches through the Pinkas Synagogue. I am the co-creator and director of a show Mikva the Musical, Music and Monologues from the Deep and have developed a new curiosity about mikvas around the world. We were shown the mikva by Jan Stefan, a music journalist who has become an expert in this as well. He told us the mikva is from the 16th century, but was discovered only 50 years ago. There is a small anteroom; I wondered if that might have been where the women prepared themselves. There is a place in the mikva room itself for a fireplace. When I asked him why he felt such a connection to the mikva, he said, “I’m from a Jewish family and a member of the Jewish community and I feel it has great spiritual power for myself and for the Jewish history of my family…”

The famed Jewish cemetery is a study in history and scholarship, ensconced in nature. Among the many luminaries buried there are the Maharal, the Kli Yakar, (one of my favorite commentators), and David Gans, a student of the Maharal who was an important historian, mathematician and astronomer. A walk through the cemetery leads to the 700-year-old Altneuschul of the Maharal, with ceilings so high you can hear an echo – of generations past? Of the elusive golem, that legend says is still in the attic? A line from Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) on the wall proclaims, “Fear God and keep His commandments for that is the whole [purpose of the] human being.”

Later we made the long trek to the Jerusalem Synagogue, not in the Jewish Quarter. The walk took us through the Old Town Square. All the buildings are so architecturally magnificent that at some point I stopped photographing them. As we wandered the square with its appeal to tourists with human statues, life-sized Mickey Mouse and a giant panda, surrounded by coffee shops, palachinka and sandwich stands, bordered by a park with tall trees and birds, and yes, the famous clock with its sculptured characters that move (that we watched chime at 4PM), I thought, what was this square used for? Who passed through it during the war? My vision changed from color to black and white as I tried to access the collective memory.

We finally reached the Jerusalem Synagogue, built in 1906, which is magnificent. It was used for a warehouse by the Nazis during the war. Today it houses a permanent exhibit on the history of the Prague Jewish community, and guest exhibits.

For a change of pace, that evening we attended an enigmatic “Black Light” theater performance; I was amazed at the creativity of the directors and cast, and at the interactivity with the joyful audience.

Theresienstadt

We spent the next day at Theresienstadt. We rented a car and rather than driving along the main highway, drove through villages and farmland. And I wondered, what did the Jews (if they could see out the cracks of the train cars) think as they the train rumbled by these peaceful villages?

Arriving at Theresienstadt is a surprise; it does not look like a concentration camp, rather it is a quaint town today, with landmarks of Jewish Holocaust-related buildings scattered throughout. The exhibits in the main building, which served, among other purposes, a gathering place for the prisoners, indicate how the Jews interred in Theresienstadt tried to have clinics, lessons, plays and concerts. It is unimaginable, and a tribute to the desire to survive, that even in those conditions of horror, hunger, starvation, and deportations to death camps, they tried to achieve a degree of “normalcy.”

We visited the train platform, and the nearby room where Jews came to bid farewell to those who had died, before they were taken to the cemetery and ultimately cremated.

But for me, the most moving part of the visit was seeing the tiny prayer room, tucked away on a side street and accessed through a private courtyard. Above the prayer room were the bare quarters of artisans, who worked for the Nazis. Even in those conditions, they had decorated the “shul” with psukim and they had painted maganei David (Jewish stars) on the ceiling, to try to replicate one of the beautiful Prague synagogues. The pasuk at the head of the room was, “And may our eyes see when You return to Zion in compassion.” Another pasuk was, “Return from Your anger and have mercy on Your chosen ones.”

We took a detour on our way back to Prague, through some beautiful forests and over a river, a stark contrast to what ensued there 70 years ago. That night we took a walk along the River Vlatava to clear our heads.

When we got back to our hotel that night, I checked my mail. At the exact moment I was standing by the theater poster display of Theresienstadt, an American Jewish playwright-director was sending me an email, consulting with me about a play he had produced about the Shoah.

Communism, a Castle and a Concert

The next day we visited the Museum of Communism, a shocking and eye-opening experience. It’s one thing to grow up in America during the Cold War, hearing about the oppression of Communism, and quite another thing to actually read the details of the cruelty, accompanied by graphic exhibits of the suppression of free speech, of the theft of homes and farms that had been in families for generations, and the details of torture and hangings. My husband’s parents came to Israel in 1949, with three young children. He turned away from one of the exhibits and said, “They just made it out. A little while longer and we would have grown up under Communism.”

Before and after that we enjoyed happier elements of the city – a boat tour, a visit to an indoor butterfly reserve, a trip to the incredibly beautiful Prague Castle and a concert of Vivaldi, Ravel and others, including Smetana’s “Vltava,” known as “The Moldau” in German, with its recognizable strains of what we know today as “Hatikva.” A circle closed.

There is a legend that the foundation stones of the Altneushul were brought from the destroyed Beit Hamikdash – the Holy Temple in Jerusalem – and that they are “on loan” until it is rebuilt.

It is customary, when one enters a synagogue, to say at least a short prayer or recite a psalm. I wished to do so, but found no prayer or psalm books in the synagogues I visited. (Perhaps they were packed away somewhere.) So I recited the first psalm that came to me, by heart, which is “A song of ascents. When the Lord returns the returnees to Zion, we shall be like dreamers.” [Translation by Chabad.org.]

What could be more appropriate than to get on a plane the next day, and fly home to the land that is no longer a dream.

The author is an award-winning theater director, editor-in-chief of WholeFamily.com, and a recent recipient of an American Jewish Press Association award for Excellence in Jewish Journalism. This article is in memory of her relatives who perished at Theresienstadt or who were deported from there to Auschwitz: Herman and Golda Bergida, and Amalia Bergida. Anna and perhaps Ilona Bergida, sisters, were liberated from Theresienstadt. Thank you to Debbi Korman for this information.