Editor’s Note: Traveling by car between San Diego and the San Francisco Bay area where their son and three grandchildren are domiciled, co-publishers Don & Nancy Harrison like to explore California’s cultural attractions.

-Second in a series-

SALINAS, California – The biblical story of Cain and Abel takes only 16 verses, but it prompted author John Steinbeck to write his longest, and what he considered his greatest book, East of Eden. In his view, it was greater even than his more famous Grapes of Wrath.

In the biblical tale, both Cain and Abel made offerings to God. Cain gave the “fruit of the ground” whereas Abel gave to God the choicest firstlings of his flock. When God spurned Cain’s gift, but accepted Abel’s, Cain was very unhappy, and so God counseled him – advice that John Steinbeck pondered very deeply.

As rendered in the Art Scroll translation for Genesis 4:7, God told Cain: “Surely, if you improve yourself, you will be forgiven. But if you do not improve yourself, sin rests at the door. Its desire is toward you, yet you can conquer it.”

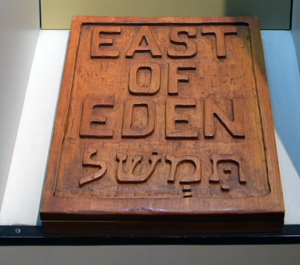

Steinbeck translated the Hebrew word “Timshel” in the last portion of that verse as meaning “thou mayest” – thou mayest conquer it.

As most readers of the Bible remember, Cain, in a fit of jealous rage, killed Abel, notwithstanding God’s advice. And God punished Cain, ordaining that Cain should become a vagrant and a wanderer of the earth. So, the Art Scroll Bible tells us, “Cain left the presence of Hashem and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden.”

In East of Eden, characters who are evil have names, like Cain, starting with “C” and those who are good, like Abel, have names starting with “A.” This applies to Adam and his brother Charles, to Adam’s wife Cathy (also known as Kate) and to Adam’s son, Aron. But, so far as Aron’s twin brother, Caleb, is concerned, whether he will be good or evil is an open question. Like Cain, Caleb resents his favored brother. But unlike Cain, he wrestles with his evil inclination.

At the National Steinbeck Center at 1 Main Street in Salinas, considerable attention is paid to East of Eden. One artifact on exhibit is a replica of the wooden box in which Steinbeck mailed his script to his editor, Pascal Covici. He carved onto the lid of the box the inscription “East of Eden” and in Hebrew lettering “Timshel.”

Steinbeck was “raised by his mom and there were a lot of Bible quotes and Bible inspiration for his work,” commented Natalia Luna, the curator of the National Steinbeck Center.

Indeed, Steinbeck came from a Bible-conscious family. In the mid 19th-century, his grandfather Johann Adolf Grosssteinbeck left Germany to start an agricultural settlement near Jaffa, in Ottoman-ruled Palestine. His intention was to teach agriculture to the Jews living in that area as a way of encouraging the ingathering of Jews necessary in Christian belief to bring about the second coming of Jesus. Johann’s brother, Friedrich, and sister-in-law, Mary, however, were the subject of a brutal attack by Arabs that left him dead and her the victim of a gang rape. Six months after the attack, Johann Grosssteinbeck (who later dropped the first part of his name) left Jaffa to live in the United States.

Yaron Perry, a scholar who researched that attack on the late evening and early morning of January 11 and 12, 1858, noted in an article for Steinbeck Studies, published in 2004, that “the brutal rape of Lee’s mother in East of Eden suggests something of the Steinbeck family history.” [1]

Hollywood turned East of Eden into a movie in 1955. Directed by Elia Kazan, it starred Raymond Massey as Adam, Richard Davalos as Aron, and James Dean as the troubled Cal. Kate was portrayed by Jo Ann Fleet, who won an Oscar as best actress in a supporting role. Dean, Kazan, and Paul Osborn, who turned Steinbeck’s script into a screenplay, also were nominated for Oscars.

An exhibit board at the museum reproduces some dialogue from East of Eden:

Adam: “You love your brother, don’t you?”

Cal: “Yes sir. And I do bad things to him. I cheat him and I foll him. Sometimes I hurt him for no reason at all.”

Adam: “And then you’re miserable?”

Cal: “Yes sir.”

There is a Model-T Ford in the museum, the very same one that was used in the movie, curator Natalia Luna, points out. In fact, as one wends the way through the museum, there are several modes of transportation which help visitors visualize Steinbeck’s life and works. There is a life-size model of a red pony, after the novel The Red Pony, in which a boy struggles to keep his pony alive. Further into the museum, there is the camper truck in which Steinbeck traveled around the United States researching Travels with Charley and America and Americans. Charley was Steinbeck’s beloved standard poodle and Rocinante was the name which he conferred upon his camper truck, in honor of the fictional Don Quixote’s horse, during a 10,000-mile circumnavigation of the USA mainland.

Although he won both a Pulitzer Prize and a Nobel Prize, Steinbeck was dogged by criticism throughout his career and even after his death. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, criticism of the choice was so vitriolic that Steinbeck, stung, decided to stop writing novels. Travels with Charley was said to be a non-fiction work, but after Steinbeck’s death, journalists followed the route Steinbeck said he had taken and concluded that much of the book was made up.

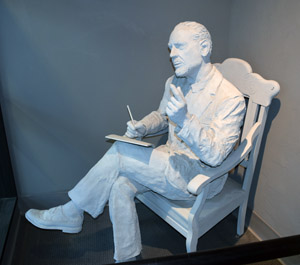

However, with the passage of time, Steinbeck’s gifts as a story teller, and the compassion evidenced in his books for working class men and women, were recognized. The people of Salinas, where he was born and raised, were particularly proud of him. The house in which he grew, about two blocks from the museum, was lovingly restored and turned into a restaurant, and citizens who knew Steinbeck began gathering and donating artifacts from his life.

The museum attracts between 50 and 70 visitors a day who pay $12.95 adult admission and three dollars less if you are a senior, student, teacher, military, or veteran. While its importance as a tourist attraction to this central California city cannot be underestimated, the museum also seeks to inspire creativity among residents of Monterey County.

“We have a Steinbeck young authors program, basically a contest and mentorship program where we allow middle schoolers to write an essay and then they are matched up with people in the community who help them edit it,” curator Luna says. “Then we publish it, and we have a small scholarship prize.”

Additionally, the museum sponsors a free symposium each year to discuss issues raised by Steinbeck in his novels. There also are festivals themed to different books written by Steinbeck. “This past August it was a Travels with Charley festival,” Luna said. “Next year it will be Cannery Row.”

The museum is laid out both thematically and geographically. Many of the books he wrote are set in the Salinas Valley, and large maps match different books to the different cities in the valley.

With an exhibit about farming are narrations about Of Mice and Men and The Red Pony. Another section of the museum deals with Cannery Row, the book and the place in nearby Monterey.

With a good friend, Ed Ricketts, Steinbeck traveled to the Sea of Cortez, and here the museum informs visitors about The Pearl, which like East of Eden ponders both good and evil. Kino and his family live a simple life until he finds a giant pearl, which he thinks will be able to purchase for him a life of relative ease. Instead, all it does is bring him grief, as thieves who will stop at nothing, try to steal it. Eventually Kino, grieving over the murder of his son, throws the pearl back into the sea.

Steinbeck, who died in December 1968 at the age of 66 , was married three times, and had two sons, but no direct descendants survive.

*

[1] Perry, Yaron. “John Steinbeck’s Roots in Nineteenth-Century Palestine.” Steinbeck Studies, vol. 15 no. 1, 2004, p. 46-72. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/stn.2004.0018.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

I’m the journalist who in 2010 repeated Steinbeck’s ‘Charley’ trip exactly 50 years later, to the day, and exposed to the satisfaction of the New York Times’ editorial page that Steinbeck and his publisher, the Viking Press, deceived the public in many ways by promoting it as the true account of his iconic road trip (which in many ways was more interesting in reality than the book’s version). Anyone interested in learning just how fictionalized, and deceitful, ‘Travels with Charley’ was is encouraged to check out my 2013 ‘true nonfiction’ ‘book Dogging Steinbeck’ on Amazon or go to http://www.truthaboutcharley.com for an accurate timeline of Steinbeck’s journey around the USA.