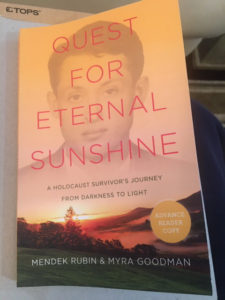

Quest for Eternal Sunshine, A Holocaust Survivor’s Journey from Darkness to Light by Mendek Rubin and Myra Goodman; She Writes Press, 2020; $16.95

RICHMOND, California — Mendek Rubin was born in 1924 in Jaworzno, Poland, a town with over 2,000 Jews, about 15 miles from Auschwitz. He died in Carmel in 2012. When his daughter Myra was putting his papers in order she came across a manuscript In Quest of the Eternal Sunshine. It was a surprise and not a surprise. It was a surprise to find it, but she had already helped her father edit it decades earlier. She worked on the manuscript for a few days but the task was incompatible with raising her two children. And, “in the intervening years” she had “completely forgotten it existed.”

RICHMOND, California — Mendek Rubin was born in 1924 in Jaworzno, Poland, a town with over 2,000 Jews, about 15 miles from Auschwitz. He died in Carmel in 2012. When his daughter Myra was putting his papers in order she came across a manuscript In Quest of the Eternal Sunshine. It was a surprise and not a surprise. It was a surprise to find it, but she had already helped her father edit it decades earlier. She worked on the manuscript for a few days but the task was incompatible with raising her two children. And, “in the intervening years” she had “completely forgotten it existed.”

Mendek’s death induced a “deep yearning to understand” her “father and uncover his secrets.” The fascinating ten-page acknowledgement indicates years of researching and writing the missing parts of her father’s story. The chief informant was Bronia, her father’s younger sister. Eight years after Mendek’s death the book appeared posthumously with his daughter as co-author, disproving the adage there is nothing as hard to publish after your death as an autobiography.

Not many unpublished manuscripts are published after the author’s death. The deceased author had the greatest interest and commitment. Their absence leaves it to friends, wives and children to complete, usually a Herculean and unsuccessful task. So much difficult work to piece together the order of the author’s mind and thoughts. Some eulogies declare friends will publish it. It rarely happens, after all the living have their own work to do. And, they are reminded of the fate of their work if they do not finish it.

I have read unpublished manuscripts of living scholars who died unpublished, and unpublished manuscripts of deceased scholars. Clearly not everything deserves to be published. Many works require additional research, documentation, and organizing. Lacking that they are destined to be rejected by commercial and university presses. Authors may attempt to self-publish, but colleagues and editors suggest revisions and further work that the author may not be prepared, willing or able to do. Successful self-publishing defeats the grim reaper. A book title in the library, or on Amazon, is sweeter immortality than a gravestone.

There is much to recommend Quest for Eternal Sunshine. Mendek survived seven different slave labor concentration camps. He came to America with his fifteen-year-old sister Bronia in 1946 sailing from Bremerhaven to New York on the SS Marine Perch, a ship incidentally built and launched at the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond in 1945. He was drafted in 1950 into the Army and spent eight months in Korea.

Mendek suffered from depression. He married Edith, an Israeli survivor who also suffered from depression. We might characterize it as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or Survivor Guilt. In America he embarked on a lifelong mission to understand and improve his state of mind. The paths he took to dig out of the hole to see the light bypassed Jewish tradition. Raised in an Orthodox home, educated in a cheder, he abandoned his upbringing, and disregarded keeping Kosher, Shabbat, and Jewish holidays.

Mendek’s story is about extraordinary immigrant entrepreneurial success accompanied by a life of melancholia. Mendek was at the same time haunted, fearful, guilty, cursed, fundamentally unhappy, charmed and lucky, and he wrote about it. He became affluent but felt poor. Mendek mentioned several times that writing helped him achieve clarity, joy and healing. His search for mental and spiritual satisfaction, healing, included hypnotherapy, Freudian, Rational, Gestalt, and Feldenkrais therapies, Primal Scream, encounter groups, a seven-year commitment to Pathways during the 1970s, Krishnamurti, and visualization.

At the heart of his masked unhappiness were unresolved issues with his father, feeling unloved as a child, the vicious experience in the slave labor camps, and the murder in Auschwitz of his mother, father and four siblings, and well over 40 cousins of his cousins.

Mendek was a problem solver, an inventor who patented economical methods to create jewelry settings to hold precious stones, and clasps on bracelets. His daughter and posthumous coauthor, Myra Goodman, founded the pioneering prepackaged salads giant, Earthbound Farms, in the early 1980s. Mendek designed the sprayers that washed the delicate greens three times and packed them attractively undamaged.

There are many unpublished Holocaust survivor accounts. Some will be printed with the assistance of the Second Generation. My Grandfather survived Theresienstadt and I managed to publish a few of his diary pages. Few accounts have Rubin’s introspection. Editors and co-authors will use written accounts, interviews, videos, Yad Vashem and other imaginative sources. This father and daughter quest to repair the traumatized mind enhances our knowledge. We are grateful that Mendek’s story did not die with him.

*

Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com