Va’era (Exodus 6:2-9:35)

LA JOLLA, California — This parasha covers Moses’ meetings with Pharaoh, which encounters result in the first seven plagues. I have chosen to pursue two Torah passages, with regard to their originality within ancient literature.

Exodus: 6:2-3 “God spoke to Moses and said to him, “I am the Lord. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai, but I did not make myself known to them by my name Yahweh.”

Hebrew Bible appearances of God include: to Adam and Eve in Eden; to Cain; to Noah, and his sons; to Abraham and Sarah; and to Hagar, mother of Ishmael. Other examples, besides Moses and Aaron, include multiple prophets, the pagan seer Balaam, and Job. Of all these, the Bible states that with Moses alone God spoke ‘mouth to mouth.’ Of course, the theophany on Mt. Sinai, with God’s voice declaring the Ten Commandments, is the core articulation in the Hebrew Bible.

An encounter of talk by a deity to a human is called a theophany. I searched the Internet for other ancient writings meeting this definition, and found precious little, and even that requires a stretch.

In Greek mythology, there is a story of a human princess, Semele, who was impregnated by Zeus. Hera, Zeus’ wife, intervened by claiming doubt of the event. Semele then appealed to Zeus to appear before her in all his glory, as proof. Apparently the prior sexual encounter and actual pregnancy wasn’t adequate. Upon Zeus’ appearance to her, she burst into flames and died. The myth concluded with Zeus saving the unborn baby by sewing the fetus into his thigh, from which the god Dionysus was born a few months later.

Christianity, in addition to acknowledging theophanies in the Jewish Old Testament, has passages in the New Testament, which are arguably theophanies. Example: In Revelation, God is described as “having the appearance like that of jasper and carnelian with a rainbow-like halo as brilliant as emerald (Rev: 4:3). Orthodox Christianity considers the baptism of Christ by John the Baptist to be a theophany.

Evangelical Christianity considers ‘pre-incarnate appearances’ of Christ in the Hebrew Bible to be theophanies. Such claims are not accepted by Jews. The apostle Paul identifies the rock that was with Moses in the desert as being Christ.

Hinduism has its own take on theophany. The god Vishnu’s appearances as a human being are referred to as Vishnu’s avatar. A non-avatar form, Nirvana Brahman, is referred to as three different supreme manifestations, the Creator, the Maintainer, and the Destroyer. [1]

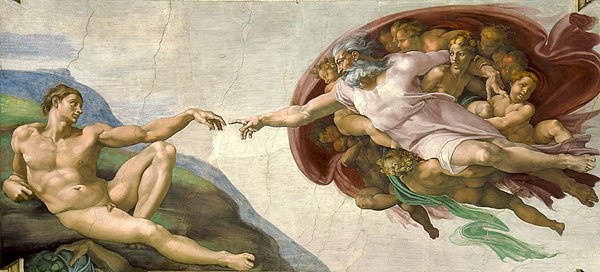

God creates Adam, a theophany as envisioned by Michelangelo, painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

II. Exodus 7:20-22 “Moses and Aaron did just as the Lord commanded: he lifted up his rod and struck the waters in the Nile in the sight of Pharaoh and his courtiers, and all the water in the Nile was turned into blood and the fish in the Nile died. The Nile stank so that the Egyptians could not drink water from the Nile…”

There follows more plagues, which seem to grow sequentially out of each other, bringing life-threatening epidemics, mainly infections related.

I have explored the internet for recorded ancient examples of infectious disease plagues. Most certainly such occurred, though were not written up. The only recorded ones I found are in Greek literature.

The playwright Sophocles, in “Oedipus Rex” (circa 428 BC) describes a lethal plague in Thebes, which to scholars was based on an actual plague in Athens in the same time frame. The playwright attributed its cause to ‘religious pollution’ by King Oedipus himself.

The historian Thucydides recorded the Athens plague. In Sophocles’ play, the first described symptom was a “weltering surge of blood.” He subsequently adds details in sporadic fashion. Early on it appears as a cattle zoonosis of high mortality rate (“a blight upon the grazing flocks and birds”) that spread to humans. There was “reek of incense everywhere” during “this fiery plague.” It led to miscarriages and stillbirths (“a blight on wives in travail”). The play’s Chorus, amidst a developing notion that the plague was incurable, pleaded for Athena, Zeus, Artemis, and Apollo to save Thebes.

Modern epidemiologists have proposed a number of possible infectious agents as the cause. The prevailing theory is that the disease was Brucellosis, an infection of cattle that indeed can spread to humans. [2]

Another Greek-referenced epidemic is described in the opening lines of Homer’s Iliad, which was composed in the eighth century BCE. Because of an insult to a priest by the warrior King Armagemnon, Apollo sets a plague upon the Greek army. It was highly communicable, with acute fever, sudden in onset and rapidly fatal. After proper appeasement of Apollo, followed by subsidence of the plague, the Greeks set about cleansing the camp by throwing ‘defilements’ into the sea. This suggests that symptoms of the plague included dysentery.

In Homer’s Iliad, the epithet attached to Apollo is ‘the mouse god,’ i.e. associated with mice, which were even then believed to be vectors of disease. [3]

*

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theoophany

[2] https://www.ncbi.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3310127/

[3] http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/antiqua/mythology

*

Irv Jacobs is a retired medical doctor who delights in Torah analysis. He often delivers a drosh at Congregation Beth El in La Jolla, and at his chavurah.