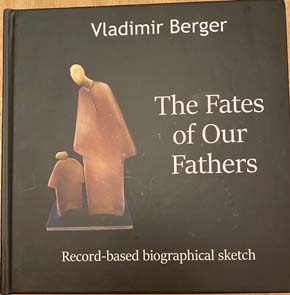

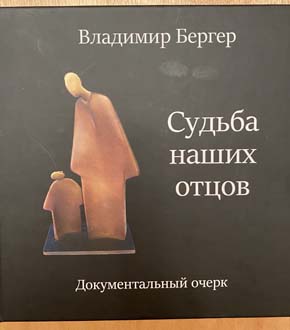

The Fates of Our Fathers, Life and Death During Stalin’s Reign of Terror, A Biography Based on Recollections and Archival Records by Vladimir Berger (Lubavitch Publishing, Saint Petersburg, Russia and Mountain View, California, 2019/

RICHMOND, California — We attended a Bat Mitzvah in Palo Alto. Our friends Marcia and Michael had spent a few years in Nebraska. We kept in touch after they moved to Palo Alto. Simchas are reunion times. We attended their daughter’s Bat Mitzvah and her wedding. Now, in the grandparent generation, we attended the bat mitzvah of their granddaughter, whose Russian born-father, grandparents and great grandparents emigrated to America in 1992.

During Sunday brunch I sat next to Raya’s grandfather, Gennady Farber. He is well educated, almost a truism for Russian Jews who came to America since the 1970s when “Freedom for Russian Jews” became a mantra. He learned English in the Soviet Union, a term he still uses to identify Russia. By profession he is a radio physicist as well as entrepreneur and avid reader. We bonded over crepes and animated discussions about books, printing and binding. He mentioned he had just published a book by Vladimir Berger, his wife’s father.

Over the years Gennady produced four books on the history of his family, published in both Russian and English. On that Sunday he expected Customs’ clearance on a press run of 80 copies of The Fates of Our Fathers by Vladimir Berger, his octogenarian geologist father in law, who was at the bat mitzvah. The book in Russian and English, is a flip flop.

Stalin ruled from the mid-1920s to 1953. Vladimir Berger was born in 1931. In 1937, at the age of 6, his father, Iosif Shmulevich Berger, was arrested by the secret police. Vladimir, his mother and sister never saw him again. The family went from being reasonably well off to selling what they had to make ends meet.

Iosif, a textile factory manager, was charged with participation in a Rightist and Trotskyite counter-revolution terrorist organizations and falsifying factory payments and prices. Torture and sleep deprivation encouraged confessions. The archives contained charges, interrogation records, sentencing and death certificates. He was sentenced to 25-years imprisonment and five years of deprivation of civil rights, a defacto if not dejure death sentence. His death certificate, identifying nephritis and hypertension as the cause of death, is suspicious. He was fully rehabilitated and exculpated, posthumously, in 1957.

Georgiy Vladimirovich Landsberg, the father of Yelena, Vladimir’s wife of blessed memory, was an electrical engineer and jazz musician. Because he had lived in Prague he was accused of spying for the Czechs and shot in 1938. The first death certificate linked death to lobar pneumonia, the second certificate records “Execution by Shooting.” In 1956 he was exculpated and rehabilitated posthumously, another example of Orwellian Newspeak, and as chilling as Arthur Koestler, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

Soviet purge justice was a sham with record-keeping; accusation, interrogation, an open and shut case, guilty verdict, and sentencing. Prisoners could outlive a 10-year imprisonment, but 10 years and no correspondence and 25-year imprisonment meant death.

The deaths of Iosif and Georgiy are a microcosm of personal, national and Jewish tragedy. The silence surrounding disappearances until Stalin’s death, the vindication and exoneration in the late 1950s, and the opening of Russian archives with the collapse of the Soviet Union is in Yelena Berger’s words a tale of truth “that seeped through darkness and secrecy.”

Communist, revolutionary and totalitarian regimes leave an all too familiar unfathomable speculative hole. The disappeared in the Spanish Civil War, Holocaust, Argentina, Chile, Rwanda, Cambodia, mass graves, refugees, and even family separation at the Southern Border, nullify humanity.

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 offered the opportunity for civilian and capitalist participation in government and the economy. The Soviet archives were opened to pursue long pent up research agendas and the opportunity for Russians to research their family history, including missing loved ones.

Ideology explains how Gandhi’s and Rabin’s killers are vilified or sanctified. When the state does the killing, as in Stalin’s case, his memory as the great leader and preserver of the revolution can obscure his bloody legacy.

Terror, purges and political cleansing is practiced in public and secrecy. The French Revolution Reign of Terror cost 40,000 lives. Stalin’s 1936-1938 Great purge took 680,000 to 1,200,000 lives. Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward took untold millions. Enormous numbers of widows, orphans and parents were left bereft, an unhealable trauma that reverberates and motivates authorship. Vladimir Berger has researched and shared his family story documented by Soviet and Russian archives, family secrets and records, internet surfing including prison archives, and memory, of tragedies that occurred eight decades ago.

Sergey Parkhomenko, the publisher, editor, journalist, political commentator, Public Policy Fellow and later Senior Advisor at the Kennan Institute of Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars wrote in the March 7, 2018 Guardian, “Russia has yet to recover from the trauma of the Stalin era,” about a potential ominous recrudescence of pride in Stalin, and at the same time a more hopeful if also mournful program called “Last Address,” similar to the Stolpersteine movement in Europe, by placing an inscribed stone, brick or plaque in front of homes from where political victims lived and were removed and murdered.

The Russian mother tongue is in flux. Eastern European Jewish adults spoke Yiddish among themselves but did not pass it on to their children. Russians love their language. Late 20th century Russian immigrants learn English and teach Russian to their grandchildren. This bilingual book can be read by both, and promises to preserve the memory of misfortune.

Thirty-six documents in Russian and English, and a log of fifteen letters reveal the tenacity of the search for disappeared husbands, sons and grandsons. The author asks, “How many unmarked graves are there where corpses of inmates were dumped?” Hopefully more survivors tell stories based on disinterred records.

*

Oliver B. Pollak, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and a lawyer, is a correspondent now based in Richmond, California. He may be contacted via oliver.pollak@sdjewishworld.com