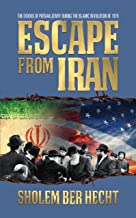

Escape From Iran: The Exodus of Persian Jewry During the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Sholem Ber Hecht, G&D Media ©2020, ISBN 978-1-7225-0294-2, p. 217, plus twelve pages of pictures, an appendix and index, $19.95.

WINCHESTER, California – Nebuchadnezzar, in the latter part of sixth century BCE, brought the vanquished Jews of Judea to Babylonia, where they lived uninterruptedly into the twentieth century through calm and turmoil, governed by the Median, Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Empires, and a theocracy under Islam and Arabic rule. Babylonian Jewry grew into a powerful Jewish force of means and scholarly learning. The latter Books of the Writings, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, and Daniel, tell their epic history and the Babylonian Talmud reveals the substantial depth of their Jewish knowledge.

WINCHESTER, California – Nebuchadnezzar, in the latter part of sixth century BCE, brought the vanquished Jews of Judea to Babylonia, where they lived uninterruptedly into the twentieth century through calm and turmoil, governed by the Median, Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Empires, and a theocracy under Islam and Arabic rule. Babylonian Jewry grew into a powerful Jewish force of means and scholarly learning. The latter Books of the Writings, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, and Daniel, tell their epic history and the Babylonian Talmud reveals the substantial depth of their Jewish knowledge.

Just as Constantine’s successors spread Christianity through the Western World beginning in the fourth century, Muhammad’s heirs spread Islam through the Middle East beginning in the eighth century. Just as Christians felt disdain for non-believers, governing them at the whim of the ruler, so too the Muslims. Iran’s Infidels, for instance, could not hold public office or practice a profession, and until 1953, when the United States pressured the new government, “Jews in all Iranian cities were made to live in Jewish ghettos, which were called the ‘Mahaleh.’”

Escape from Iran is a passionate, first-hand accounting of the monumental, and arguably miraculous work of its author and his father, Rabbi J.J. Hecht, as they sought to bring as many Jewish-Iranian children to America as possible during the Shah’s last year of rule and the beginning of the Khomeini regime.

Escape from Iran is essentially divided into two parts, the first telling of Hecht’s initial trip to Tehran in which he provides a wonderful study of the ambient culture. In the late 1970s, most of Iran’s one hundred thousand Jews resided in Tehran, living stable, and in some cases, wealthy lives under the Shah. Yet, Hecht, a rabbi of a Sephardi synagogue with many Iranian congregants, and other rabbis and lay persons in the New York City area were concerned about “the state of Jewish education and its impact on the lives of the Jewish community,” resulting in an exploratory visit.

Hecht begins accessing Tehran’s Jewish community soon after his arrival in August, 1978, by visiting numerous school and synagogues, living in hotels owned and operated by Jews, staying in homes of rabbis for the Sabbath, and meeting with prominent Jews and college students. He tells of trouble finding kosher establishments and complains of “a strange, fuzzy, sponge-like ‘thing’” floating out of his bottle of cola.

While describing his visit to Tehran’s Mashhadi community, Hecht reveals the history of Mashhadi Jews, who independently developed their own customs living in isolation following Islamic persecution for blood libel in 1839. At each stop, we are treated to characterizations of the physical and affective environments, noting both their beauty and isolation. “Somehow, however, people manage to penetrate the barriers and develop social milieu.” The chaos of confrontation, first by anti-government protesters, then by ‘radicalized youth,” and finally Islamic extremists, began brewing just at the time of Hecht’s visit, whose purpose morphed from a plan to support Judaism in Iran into a plan to rescue Iranian-Jewish children.

The second part describes the development and execution of the plan, simple on paper; difficult in implementation. Hecht needed educational institutions to admit the elementary and high school-aged Iranian students, and places for them to stay. He needed volunteers to complete the required Federal I-20 student visas, and other forms demonstrating sufficient financial resources, and because of Iran’s political instability, parents could not guarantee a continuous flow of money; he needed American sponsors guaranteeing financial support. Yet, even with all of these in place, the students required the US Embassy’s approval in order to obtain an F-1 visa, the actual student visa, at the time of anti-American violence and eventual capture of the embassy and holding hostage ninety-six of its employees (who were eventually released after 444 days in captivity).

The first Iranian students arrived in the United States in early 1979, and by September, over twelve hundred reached New York. These students needed care and attention, such as: safeguarding the money in their possession and ensuring proper use, seeing that Sephardi customs were followed, especially serving rice, for example, during Pesach, handling the inevitable culture shock, and finding appropriate educators so that students could obtain a NY State Regents diploma.

Hecht describes how the volunteers met and conquered these challenges, while showing compassion and understanding for the students. For instance, on his visit to Tehran he learned Tehranian Jews often vacationed in the Alborz Mountains, in northern Iran. In America he provided summertime escape from the city in the Catskills. Hecht also honors the volunteers in Escape from Iran by naming them and recounting their deeds. Escape from Iran is a feel-good book detailing the devotion of several hundred American Jews working unstintingly to save thousands of Jewish-Iranian children during the time of the Khomeini revolution, and in the process providing a safe haven and a Jewish-centric education.

*

Fred Reiss, Ed.D, is a retired public and Hebrew school teacher and administrator. His works include: The Comprehensive Jewish and Civil Calendars: 2001 to 2240; The Jewish Calendar: History and Inner Workings, Second Edition; and Sepher Yetzirah: The Book That Started Kabbalah, Revised Edition. He may be contacted via fred.reiss@sdjewishworld.com.

Pingback: Rescue Brought Iranian Jewish Children To U.S. | Iranian Diaspora