Editor’s Note: Following is another in a series of stories by our music writer Eileen Wingard on the discography of her sister, violin soloist Zina Schiff.

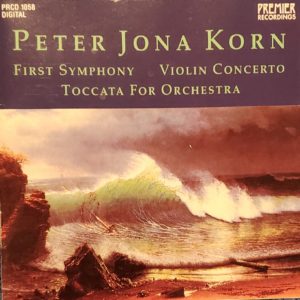

SAN DIEGO — My sister, violinist Zina Schiff, has championed the works of many contemporary composers, as illustrated by her recordings. The 1998 release of the Peter Jona Korn (1922-1998) Violin Concerto was a result of my friendship with the composer. At its US premiere with the Baton Rouge Symphony, Korn’s friend, Peter Paul Fuchs, was the conductor; the country’s foremost music magazine, Musical America, came to review the concert; and the composer himself, was in the audience.

The May, 1974 edition of Musical America printed the critic’s impressions of the Baton Rouge concert: “This exciting new work …won its approval before a large and enthusiastic audience. It is difficult to determine how much excitement was generated by the composition itself, by the virtuosity of Miss Schiff, or by the orchestra…it was an impressive combination.”

The review concluded, “ Miss Schiff, obviously in accord with the composer’s style and intent, enhanced the first U.S. hearing of this work with her dazzling technique and her devoted attention to the score.“

Over two decades later, and shortly before his death, Peter Jona Korn was able to arrange for the recording of this work with Zina as soloist with the Hofer Symphony Orchestra. This recording also includes Korn’s First Symphony and his Toccata for Orchestra.

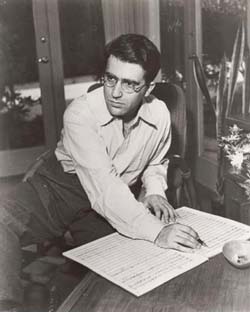

I first met Peter Jona Korn when my high school friend, cellist Roberta Harrison, got me my first professional gig, playing for Dark of the Moon, a play with music, based on the folk ballad, Barbara Allen, sung by a still-little-known Pete Seeger. Earl Robinson had written the incidental music for the play and conducted us for five of the six week run, but Peter Korn, then assistant conductor of the Pasadena Orchestra, took over our final week because Robinson had another commitment.

Peter Korn then invited me to be a member of his New Orchestra of Los Angeles,which was comprised of professional studio musicians, who longed to play symphonic literature, and students, like myself, who appreciated the valuable opportunity of playing beside professional musicians and under a fine conductor.

At the age of eleven, Peter was already recognized as a child prodigy, enrolled in composition classes at the Hochschule fuer Musik in Berlin. When, in 1933, his parents saw the handwriting on the wall with the onset of Nazi rule, Peter, his parents and his sister moved to England. There, he became enamored with the music of Ralph Vaughan Williams and studied in London with Edmund Rubbra.

In 1936, at the age of 14, he was awarded a visa to go to Jerusalem to study with Stefan Wolpe at the New Jerusalem Conservatory. After two years, he transferred to Tel Aviv, where he became a student of Herman Scherchen. Peter’s father died in 1940 and he, his mother and sister moved to the United States, settling in Los Angeles. There, he attended UCLA, then, USC. Although his teachers included Arnold Schoenberg, Peter never adopted atonality. He also took classes with Miklos Rozsa on film scoring, but never worked in the film industry, except for the orchestration of one film score, which his good friend, Ernest Gold, wrote for It’s a Mad, Mad World. Gold was also a struggling composer at first and served as the personnel manager for Peter’s orchestra before his successful scoring of the film, Exodus. Although many of the Jewish refugee musicians from Europe were able to do well as transplants, others, such as Peter, struggled.

After moving back and forth to and from Europe several times, Peter, his wife, Barbara, and their two children, Heidi and Tony, finally settled in Munich where, in 1967, he was appointed Director of the Richard Strauss Conservatory, a post he held for two decades.

During that time, he not only continued composing, but he wrote his book, Musikalische Umweltverschmutzung (Musical Pollution), in which he railed against “theoretical” music and its inability to express or even mean anything. He refused to join the avant garde and he prophesied that “the era of experimental music will one day come to an end and composers would find their way back to the realm of tonality and clarity.“ In 1968, Peter Jona Korn was awarded the Music Prize from the city of Munich.

While my husband, Hal, two-year-old daughter, Myla and I were in Tauberbischofsheim, Germany under the Fulbright program, we visited the Korns in Munich on several occasions. We remained in touch over the years, and, when I introduced him to my younger sister Zina, he recognized her talent and invited her to present the United States premiere of his violin concerto.

This is the final movement of the work, subtitled, Rondo all Tarantella.

Eileen Wingard, a retired violinist with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra, is a freelance writer specializing in coverage of the arts. She may be contacted via eileen.wingard@sdjewishworld.com

THANK YOU AGAIN & AGAIN, DEAR FRIEND EILEEN!!

WHEN OH WHEN WILL YOU CONSIDER WRITING YOUR FASCINATING LIFE HISTORY INTO BOOK FORM?????

AT LEAST ALL THE MUSICAL PARTS OF YOUR OH SO INTERESTING LIFE’S STORY???

I WOULD LIKE TO ASK YOU ABOUT PETER JONA KORN….. DID HE COMPOSE FOR THE PIANO AT ALL>>??? OUR DEAR FRIEND AND SUPER TALENTED PIANIST & PROMOTER OF JEWISH COMPOSERS DANIEL VNUKOWSKI,

WOULD SURELY BE FASCINATED TO PERFORM PETER’S COMPOSITIONS…… HE IS ON YOU TUBE AND ALSO ON FACEBOOK PROMOTING COMPOSERS LIKE ERICH MARIA KORNGOLD AND RATHAUS, BOTH OF WHOM HE PLAYED AT OUR “SOLANA SALONS” WHEN, I BELIEVE, YOU WERE PRESENT??

THANK YOU FOR EVERYTHING YOU DO AND SHARE WITH ALL YOUR JAVERIM!!