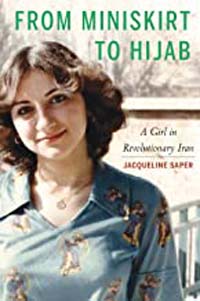

From Miniskirt to Hijab: A Girl in Revolutionary Iran, Jacqueline Saper, Potomac Books ©2018 ISBN 978-1-64012-117-1, p. 206, plus pictures and appendices, $29.95.

WINCHESTER, California – As insiders, we know the Khomeini Revolution of 1979 changed America’s perception of itself, learning of its broken military and its failed attempt to rescue the fifty-two US Embassy hostages—three wrecked helicopters, a plane collision, and eight dead soldiers. As outsiders, we watched the same revolution oust a progressive monarch in favor of an Islamic fundamentalist cleric. But what was it like to be an Iranian insider?

WINCHESTER, California – As insiders, we know the Khomeini Revolution of 1979 changed America’s perception of itself, learning of its broken military and its failed attempt to rescue the fifty-two US Embassy hostages—three wrecked helicopters, a plane collision, and eight dead soldiers. As outsiders, we watched the same revolution oust a progressive monarch in favor of an Islamic fundamentalist cleric. But what was it like to be an Iranian insider?

Author Jacqueline Saper, part of a Jewish family, the daughter of an Iranian university professor and a British mother, an assistant airport manager, describes growing up in a wealthy and idyllic setting, a large house with opulent furnishings in the Tehran neighborhood of Yousefabad, dining in the best restaurants, attending private schools, travelling back and forth between England and Iran, and surrounded by maids and household laborers.

She also tells of the increasing encroachment of “decadent” Western values—American movies, clothing, and music—on parts of Iranian society, the wealthiest parts, but she also elaborates on the growing economic chasm between rich and poor and the unpopular fiats of the Shah, such as abolishing the multiparty system and rejecting the Hijri Shamsi calendar, which “is tied to the Prophet Mohammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina.”

The Shah raced to modernity faster than the majority desired, and the disconnect between permissiveness and culture became the tinder from which the fire of upheaval emerged; quiet at first, in xenophobic and anti-non-Muslim religions whispers. In the summer of 1978, Saper, vacationing in England and ready to return home, learns of both rioting and deadly shootings in Tehran. The first sign she reads on returning to Mehrabad International Airport hold the unimaginable words, “Death to the Shah”.

Saper describes 1978 and 1979 as fearful years, years having numerous riots and strikes against both private and government-owned industries in the name of Ayatollah Khomeini, whose political influence, she recalls, belies “his image—that of a kind, elderly grandfather.” The nightly 8:55 pm shouting out of “Allahu-Akbar” in the darkened streets of Tehran from rooftops and balconies were terrifying. By now, many Jewish families, in panic, made arrangements to leave the country. Describing her synagogue, Saper writes, “Every week, the prayers were the same, but fewer people attended…. Many of my classmates had already left Iran, and each week I noticed that even more friends were absent.”

The Shah flees, a broken man; Khomeini arrives to jubilant crowds. Saper’s father, in denial, believing all would pass, refuses to leave. The author could not escape either. Newly betrothed, her future husband had two more years of surgical residency ahead of him, which, because of deteriorating circumstances, lasts much longer.

Sapir tells about her new home in Shiraz, her husband’s city, smaller and less cosmopolitan than Tehran, a ninety-minute plane ride to the south, just as Iraq declares war on Iran. She lives in a constant state of anxiety, and we become immersed in her experiences: Now forced to wear a head scarf covering every strand of her hair, or be carted off to jail by the moral police. Now learning that males and females must be separated—in the schools, on the beaches, in buses, and hair salons. Now fearing being discovered as a Jew, Muslims believe an object touched by a Jew is dirty, but having greater fear of being thought of as a member of the Baha’i faith, whom the Muslims hate even more. By day, she sadly sees her six-year old daughter wearing a hijab and reciting verses from the Koran in Arabic, and at night crouches in basements to escape Iraqi aerial bombings.

Her husband finds a surreptitious, but legal way out for the family, but whose escape at the airport is not without stomach-wrenching incidents. Not until the family is out of Iranian airspace do we dare exhale.

Saper places us in the front row of her first twenty-five years, granting the privilege to experience her love of life, her empathy for others, her fears and resolve, as she watches her beloved country sink into the slough of despondence under the weight of an intrusive and repressive theocracy.

In addition to being a memoir of resiliency and courage, From Miniskirt to Hijab offers glimpses into Iran’s history and customs, its arts and laws, how its social institutions operate, and its people think. From Miniskirt to Hijab: small in size, powerful to read.

*

Fred Reiss, Ed.D. is a retired public and Hebrew school teacher and administrator. His works include: The Comprehensive Jewish and Civil Calendars: 2001 to 2240; The Jewish Calendar: History and Inner Workings, Third Edition; and Sepher Yetzirah: The Book That Started Kabbalah, Revised Edition. He may be contacted via fred.reiss@sdjewishworld.com.